“I left Ulm on 23 May in the year 85. It was a Sunday. My brother and some good friends accompanied me to Güntzburg. In the town, we had lunch and refreshed ourselves. Afterwards, I said my goodbyes and went on a raft on the Danube.“1

From Ulm to Lauingen

23 May 1585

On 23 May 15852, a young man named Samuel Kiechel left his home in Ulm and walked out of the city gate. He crossed the bridge over the Danube and, maybe, looked back one last time. What was on his mind? Was he brimming with excitement for the adventure that lay ahead? Was he anxious, knowing that a journey held many dangers and that he might not return?

Samuel was about to embark on an adventure that would, in the end, take four years and cover over 30,000 kilometres (~ 19,000 miles). He would visit popular places like Elizabethan London, Venice, Rome and Jerusalem. However, his curiosity would also take him to Scandinavia, Lithuania and Livonia in the north and north-east of Europe and down the Italian Peninsula to Sicily and Malta. A summary of the journey is found here.

The Traveller Samuel Kiechel

Born in Ulm in 1563, Samuel was the son of Matthäus Kiechel, a craftsman, successful merchant and member of the guild of cloth shearers. Matthäus Kiechel held various official positions in Ulm. However, the Kiechels were a relatively new family and not part of the patriciate — the old, established dynasties of a city. The family’s name was first documented in Ulm’s records in 1501 when the barber Lorenz Walter Kiechel was granted citizenship.3

From barber to craftsman and successful merchant, the family became wealthy and influential within a remarkably short time. With their newly acquired status among the elite of Ulm and presumably with ambitions to join the ranks of Ulm’s patricians, Samuel’s parents wanted to provide their sons, Samuel and his older brother Daniel, with the right start in their careers. They received an education appropriate to their social rank to prepare them to take over their father’s business.4

Travelling was considered the finishing touch to the education of a young man from a wealthy family. Initially, it was the preserve of noble families. However, merchants and wealthy citizens began to copy this behaviour and adapt it to their circumstances.

The journeys usually followed a set pattern. A young man travelled with a friend, family member, teacher or, depending on their wealth, servants. He would follow a pre-planned route and visit specific, predetermined places and people. Merchants would send their sons abroad to learn and work in the business of a friend, a family member or a trusted partner. Young noblemen would spend time at foreign courts to be introduced into aristocratic society, learn about etiquette and establish social contacts. Travellers from both social groups also travelled to study at a university or visit places of religious significance. A successful journey promised prestige and career advantages for the traveller and would gain popularity under the name ‘Grand Tour’ in later centuries.

Samuel Kiechel’s journey diverged from the established behaviour of his peers. His family had come to wealth within a few decades and presumably had not yet established a network of friends, family and business partners in Europe to support Samuel’s journey. Just as the elite in the cities modelled the educational journeys of their sons on the behaviour of the nobility, the Kiechels copied their peers’ behaviour and sent their son abroad. However, as his journal shows, without experience and connections, Samuel Kiechel followed his interests and inclinations. Left to his own devices, his behaviour shows similarities to modern backpackers.

The Journal

Samuel Kiechel left behind a journal of his adventures that provides a rare glimpse into the daily life of a sixteenth-century traveller. Kiechel was no habitual or eloquent writer; his style is somewhat unreflected and immediate. The uneven and haphazard nature of the journal entries suggests he wrote them without an audience in mind. The journal was likely just a private token of remembrance or a form of report. Samuel wrote in his native Swabian dialect and did not include an introduction or customary dedication to a benefactor, mentor, or his parents.

Unlike many of his contemporaries, who often described the places they visited in detail or engaged in discussions on political, cultural, or religious topics, Kiechel focused on the practicalities of travel. He wrote about stubborn horses, the availability of food and drink, and the various temporary companions he had encountered along the way. His personal experiences appear genuine, and he refrained from exaggeration and self-promotion. Uncomfortable experiences and mistakes are neither omitted nor trivialised.

Although the original manuscript is lost, its contents have been preserved in a handwritten copy from the seventeenth century and a printed edition from 1866. The first page of the handwritten copy features a picture of the traveller. It is part of the Ulm Library collection.

The printed edition of the journal was published by Konrad Hassler in 1866. Hassler still had access to the original manuscript while preparing his work. This edition is available online for anyone interested in reading it firsthand.

Ulm in the 16th Century

Samuel Kiechel’s hometown of Ulm is in the southwest of modern Germany. The city is perhaps best known for being the birthplace of Albert Einstein and for the Ulm Minster, a gothic church with the tallest church tower in the world. Our traveller, on the other hand, is mostly unknown. The Kiechelhaus is what remains of the family. Samuel’s father bought the house in 1583. His older brother Daniel inherited it in 1599 and rebuilt it. Today, the Kiechelhaus is part of the Museum Ulm.

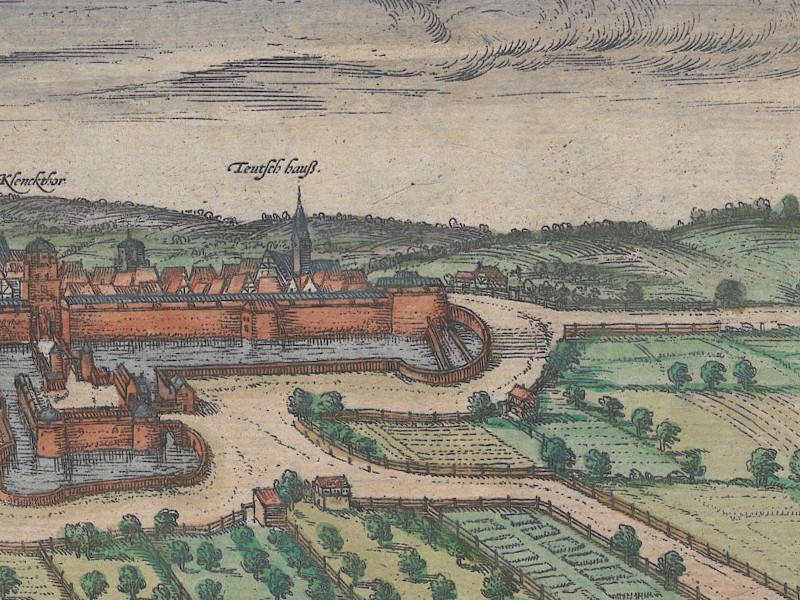

Ulm, 1593

The above view of Ulm from the sixteenth century shows a city exuding wealth and power. Sturdy walls and a moat protect the houses within them. Around Ulm are orchards, gardens and small fields. The majestic Ulm Minster dominates the view. Its construction had not been financed by the church but by the citizens. Despite its size, the Ulm Minster is a church, not a cathedral.

The view is from the north and does not show the Danube as it passes Ulm to the south. The Herdbrucker-Gate (“Vertpruckthur”) is highlighted in the image. It is in the background beside the town hall. The gate and connected bridge were the city’s main access to and across the river.

A part of Ulm had been destroyed during World War II, but there are still some sights that existed in the sixteenth century that you can still visit today, like the Ulm Minster, town hall and Gänsturm.

Textiles were the source of Ulm’s wealth. Fustian was a type of cloth woven from cotton and linen. It was a commodity of wide renown. The fustian made in Ulm was of the highest quality and exported to places all over Europe. At times, it was even used as a substitute currency.

When Samuel Kiechel left Ulm in 1585, the city had already passed its peak. In the fifteenth century, Ulm had been one of the wealthiest places in Germany. The city’s domain outside its walls included three towns and fifty-five villages. Ulm’s citizens could afford to pay for the construction of their majestic minster.

But then, the political fallout of the Protestant Reformation took its toll. The citizens of Ulm had voted for their city to become Protestant in 1531. As in other cities, the destruction of Catholic art and church decorations accompanied this process. Many altars were destroyed or removed, sixty alone in the Ulm Minster.

‘Bildersturm’, the destruction of Catholic art and church decorations

Ulm became a member of the Schmalkaldic League in 1531. The League was a defensive alliance of Protestant princes and free cities against the Catholic Emperor Charles V’s attempts to restore religious unity. The political conflict turned into a military confrontation in 1546 (Schmalkaldic War 1546/1547). In the war, thirty-five of the villages in Ulm’s territorial domain were sacked or burned down. The city struggled to pay for the war due to the lack of income from its domain and the disruption of trade due to the conflict. In 1546, Ulm surrendered to Charles.

In the aftermath of the surrender, the city had to sign a peace treaty with the Emperor. Ulm had to pay compensation, and the city’s guilds were abolished. The guilds posed a particular concern to Charles V, as they held political power and were considered a hotbed of Protestantism. Charles changed the municipal constitution and handed control of Ulm to the city’s patricians. Despite this, Ulm remained a Protestant city, and ten years later, the guilds were permitted to be re-established.

In the second half of the sixteenth century, Ulm had recovered economically, though it did not return to its previous level of prosperity. Nevertheless, the trade in textiles flourished enough for families like the Kiechels to prosper and finance their sons’ long journey.

Leaving Ulm

Samuel Kiechel mentioned his departure from Ulm only briefly. He did not leave his home alone. Accompanied by his brother and friends, he travelled to Günzburg on the Danube, twenty-three kilometres downstream of Ulm. The distance and the fact that they arrived in the town at lunchtime suggests that the group travelled on horseback.

In Günzburg, they had lunch. Kiechel confusingly referred to the meal as “morgen essen”. The first part, ‘morgen’ (Morgen (n.): morning), refers to a meal in the morning and could be interpreted as breakfast. Samuel would use this term regularly, but always after he had already travelled some distance and at what could only be considered lunchtime.

Afterwards, Samuel said goodbye to his brother and friends. A raft was moored at the bank of the Danube. It belonged to a man named Marte Clonz. The raft had already many passengers on board. Kiechel noticed Anabaptists, Jesuits, Martinists and Papists as well as various journeymen and women. He went on board, and the raft began its slow journey downstream.

Kiechel’s remark on the various passengers is a sure sign of the aftermath of the Protestant Reformation and the tensions it brought. Under other circumstances, it is questionable if religious affiliation would have been the first comment about a person.

River Transport

In the sixteenth century, the choice of transport was limited. Wealthy travellers often had their coach or horse; poor people tended to walk or hitch a ride in the back of a cart. However, road conditions were poor, which Kiechel regularly pointed out in his journal. Paved roads were expensive to construct and maintain. Most roads were dirt tracks that quickly became mires in wet weather.

Where a river was available, people preferred to use boats and barges to travel. It was a faster and more comfortable alternative to land travel and allowed more cargo to be transported. Rafts were another form of river travel. On the Danube, wood was cut in the forests upstream, tied together into rafts and floated down towards cities like Ulm, Regensburg or Vienna. Transporting passengers was a common practice. It allowed the men working the rafts to generate additional income.5

Final Goodbyes

Like modern public transport, the rafts on the Danube stopped at all towns to allow people and cargo to get on and off. Samuel Kiechel left his raft at Lauingen, just a short distance downriver from Günzburg. Kiechel’s parents lived there, and he wanted to bid them farewell.

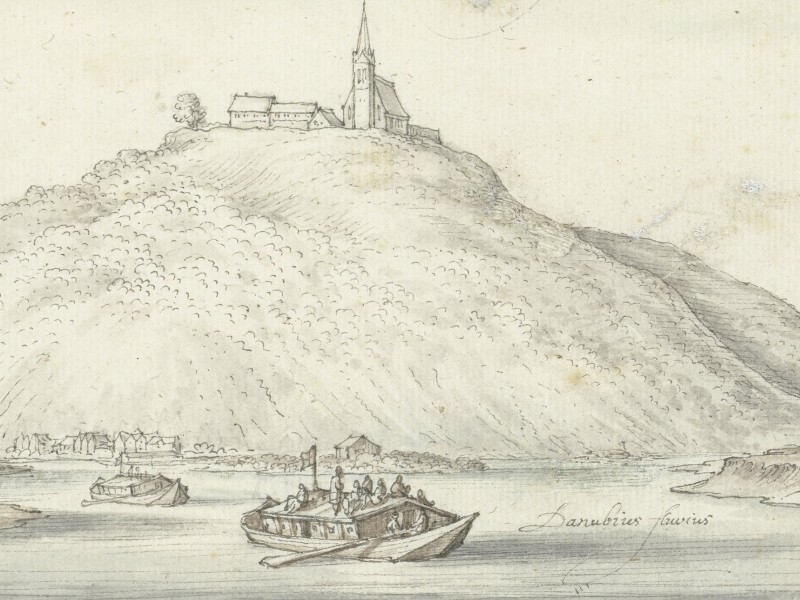

Lauingen, 1594

This view of Lauingen is a neat summary of what Samuel might have seen: a rather majestic-looking but provincial town, the Danube and the countryside he had travelled through. A welcome extra for the illustration of Kiechel’s journey are the two rafts in the foreground — one moored at the northern bank of the Danube and the other floating down the river.

Kiechel spent the night in Lauingen. He left in the morning with his parent’s permission and blessing.

To our ears, it might sound strange that a twenty-three-year-old adult asked his parents for permission to go travelling. But this was far from uncommon at the time. The journey was a new and intermittent stage in the young man’s life — between youth and adulthood. It was a once-in-a-lifetime experience and could be the cornerstone of a successful career after his safe return. Or it could end in tragedy. For Samuel and his parents, the moment of departure was undoubtedly heavy with excitement and apprehension, expectations and aspirations, sadness and worry.

Illustrations & References

All images are in order of appearance with links to sources on external websites:

- Hollar, Wenceslaus: Gezicht op de Donau bij Ober-Alteich, ca. 1625-50; Rijksmuseum Amsterdam.

- Saftleven, Herman: Een zittende en drie staande mannen, 1619 – 1685; Rijksmuseum Amsterdam.

- Verbeeck, Pieter Cornelisz., Twee ruiters, 1620 – 1654; Rijksmuseum Amsterdam.

- Ulm, in: Braun, Georg, Hogenberg Frans: Civitates Orbis Terrarum (1), Cologne 1593, fol. 31v; Heidelberg University.

- Hogenberg, Frans, Beeldenstorm, 1566; Rijksmuseum Amsterdam.

- Brueghel, Jan: View of a City along a River, ca. 1630; Rijksmuseum Amsterdam.

- Lauingen, in: Georg Braun, Frans Hogenberg: Civitates Orbis Terrarum (4), Cologne 1594, fol. 45v; Heidelberg University.

- Die Reisen des Samuel Kiechel aus drei Handschriften, K. D. Haszler (ed.), Stuttgart 1866, p. 1; Bayerische Staatsbibliothek. ↩︎

- Both the Julian and the Gregorian Calendar were in use. Pope Gregory XIII instigated a calendar reform in 1582. The Catholic realms of Europe adopted the new calendar, but Protestants refused. Ulm would not adopt the new calendar until 1700, so Kiechel used the old Julian calendar in his journal. To avoid confusion with the journal, I use Kiechel’s dates. The date of departure in the Gregorian Calendar was 02 June 1585. ↩︎

- von Koenig-Warthausen, Gabriele, Die Reisen des Samuel Kiechel 1585-1589, in: Ulm und Oberschwaben. Zeitschrift für Geschichte und Kunst , Vol. 34, 1955, pp. 66-75. ↩︎

- Specker, Hans Eugen, “Kiechel, Samuel” in: Neue Deutsche Biographie 11 (1977), pp. 575-576; URL: https://www.deutsche-biographie.de/pnd128823844.html#ndbcontent ↩︎

- Birgit Jauernig, Flößerei, in: Historisches Lexikon Bayerns. ↩︎