A journey, a rare and often once-in-a-lifetime experience in earlier centuries, was a feat of courage and curiosity. The idea of travelling for leisure was still unknown. Detailed travel guides filled with practical information to help prepare for the experience did not exist in the early modern period. The choice of travel resources and their quality were much more limited.

As a result, for many people, their town or village and the surrounding countryside defined their horizon, a boundary rarely crossed. In such circumstances, a journey was an expedition into a world that was known and somewhat familiar in places, but also mysterious, sometimes frightening, hostile, or simply unintelligible.

Guide Books in the Sixteenth Century

Itineraries and Road Maps

Samuel Kiechel did not mention how he prepared himself for his journey. According to his background as the son of a wealthy merchant, he had received a good education and had certainly some geographical knowledge about Europe. But it is difficult to say how thoroughly he planned his adventure.

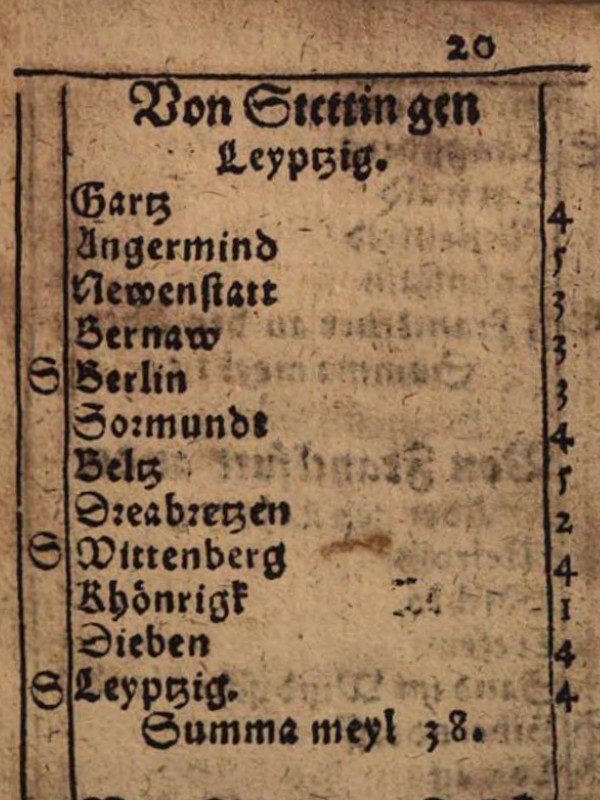

One source of helpful travel advice he might have perused was Itineraria. Itineraries were already known and in use in the Middle Ages. They were usually lists with the names of cities, towns, and villages along a road to a specific destination, often including the distances between the various waypoints. They could have been written to guide travellers, often pilgrims, to a particular destination or as a form of travelogue, detailing the route a traveller, usually a prominent figure like a king, had taken.

Page of an itinerary, 1612

Itineraries underwent a significant evolution after the invention of the printing press in the fifteenth century. Individual itineraries were collected and published as guidebooks to the road networks in Western and Central Europe, marking a significant leap in the history of travel. The roads described were the most heavily frequented routes at the time, connecting important political and commercial places. Itineraries could contain additional information, such as symbols denoting postal stations, inns and intersections with other major routes. The intersections allowed a degree of freedom while using itineraries. Travellers could change routes to reach their destinations.

It is important to note that itineraries were textual descriptions and not, as is the case today, maps. Some early modern collections included regional maps with the places mentioned in the book highlighted. However, those maps were of limited use due to their small scale.

Part of the map by Erhard Etzlaub. The map is oriented southwards. Bohemia appears in the lower left corner, the Alps are in the centre, and Venice is at the top.

A notable exception to the textual form of itineraries is the “Romweg”-Map (Roads to Rome) by Erhard Etzlaub. Etzlaub was a cartographer and physician from Nuremberg. In preparation for the many pilgrims visiting Rome for the Catholic jubilee year of 1500, he created a woodcut map showing the roads from the Holy Roman Empire to Rome. The text at the top of the map states: “Daß ist der Rom-Weg von meylen zu meylen mit puncten verzeychnet von eyner stat zu der andern durch deutzsche lantt” (“This is the road to Rome, from mile to mile marked with dots from one town to the next, through Germany”). Dotted lines indicate the roads to Rome, with each dot representing one mile. While road maps are common today, this map was a novelty at the time. It was valuable for planning a pilgrimage to Rome.

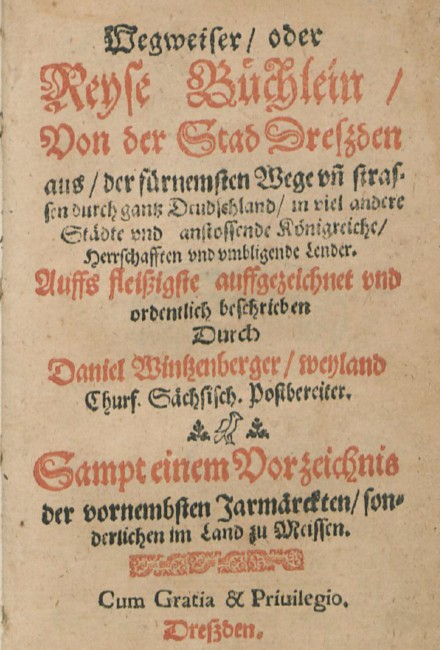

The Itinerary of Daniel Wintzenberger

Title page of Wintzenberger’s Itinerary of Dresden, 1597

A qualified person to write an itinerary of the major roads would, for example, be a messenger. Such a person was Daniel Wintzenberger. Wintzenberger was a messenger of the Prince-Elector of Saxony. He wrote two itineraries about the roads he knew and had travelled. The first itinerary contains routes from Dresden to various destinations across central Europe. Dresden was the residence of the Prince-Elector and the principal city of the Duchy of Saxony. The book was first published in 1578 and reprinted in 1597.1

The second itinerary, published in 1595, is about routes from Leipzig.2 Both books contain similar routes because Leipzig is not far from Dresden. Presumably, this itinerary was a partial copy of the first. But it includes some additional information.

Guiding Travellers through Sixteenth-Century Europe

The itineraries of Daniel Wintzenberger are an example of the kind of information a traveller could obtain from them. The two books are by no means comparable to modern travel guides. They contain no practical advice about accommodation or food in the places they mention. Nor do they offer detailed information about the cities and towns. However, they would be useful to a traveller preparing for a journey when choosing the correct route to a specific destination.

In his foreword, Daniel Wintzenberger clearly states his intentions and the particular audience he had in mind. The purpose of the itineraries was to guide people along the correct routes from one city to another. The audience he had in mind included merchants, fellow messengers, post riders, journeymen, and travellers.

The Itinerary of 1578 begins with a list of the larger European kingdoms, their rulers, and capitals. The subsequent section lists the Prince-Electors of the Holy Roman Empire and their residences.3 These Prince-Electors were the highest-ranking nobles in the Empire, responsible for electing the Emperor. It also features a comprehensive list of regional lords, bishoprics, and lower nobility (counts) and their extensive domains within the Empire and beyond.

Routes

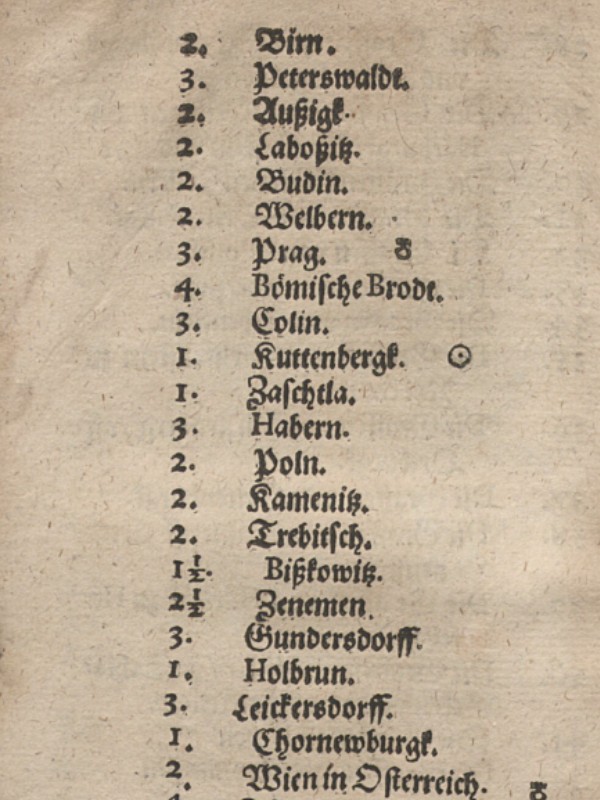

Route from Dresden to Belgrade, 1578

The next part of Daniel Wintzenberger’s itinerary contains the actual routes. The first route leads from Dresden via Prague, Vienna and Budapest to Belgrade. The description lists the towns and villages along with the distances between them. At the end of this description, we find the total distance between Dresden and Belgrade (162 German miles ~ 1.200 kilometres4). The first leg of this route is the same one Samuel Kiechel took on his way from Prague to Dresden. The locations mentioned in Kiechel’s journal are also in Wintzenberger’s itinerary.

Following the routes, an extensive index lists the rivers within the Empire, along with the towns and cities on their banks. Rivers were vital for travel and trade, offering natural and relatively safe passage. Another list details the rivers in neighbouring countries and the towns and cities along the coastlines of the North Sea and the Baltic Sea. To return to the practical considerations, Wintzenberger also notes all toll stations along the river Elbe, along with the regional lord or city to which they belonged.

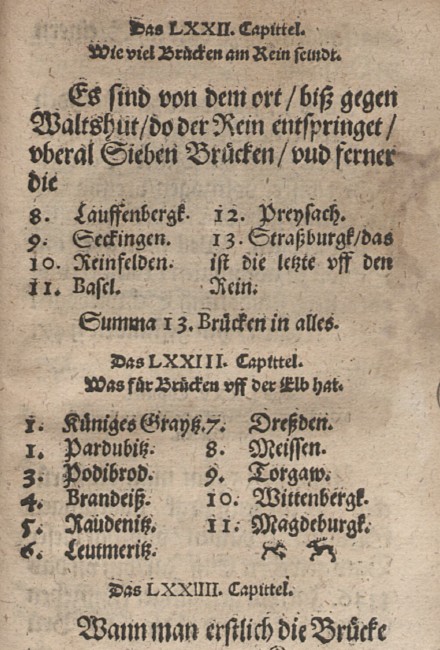

Bridges

Stone bridges represented a remarkable feat of architecture in early modern Europe. Kiechel frequently mentions them. Our traveller described the beautiful bridge over the Vltava in Prague, and he will comment on the delicate stone bridge in Dresden. Bridges were a crucial part of Europe’s infrastructure. Compared to ferries, they allowed for easy and safe crossing of large streams and often served as symbols of a city’s wealth and power.

Wintzenberger’s itinerary includes a list of eighteen major stone bridges along the routes in his book and recounts the bridges over the Danube, Rhine, and Elbe rivers. Three short paragraphs describe the stone bridges in Dresden, Regensburg, and Prague — all visited by Kiechel.

List of bridges across the Rhine and Elbe from Wintzenberger’s Itinerary, 1578

About Dresden, Wintzenberger states that the first stone bridge was built in 1119, taking thirty years to complete. The bridge had twenty-four arches. Due to the reconstruction of the Ducal Palace, the bridge was shortened by five arches.

The Regensburg stone bridge was finished in 1146 after eleven years of construction, featuring fifteen arches. Lastly, Prague’s bridge has sixteen arches. However, Wintzenberger admits he does not know when its construction started.

Fortifications

Furthermore, Wintzenberger documents the major fortresses in the Holy Roman Empire and neighbouring territories. He divides this list into the fortresses of the Emperor, the Prince-Electors, and various regional lords. He also mentions noteworthy fortified cities within the Empire. To conclude this part of the itinerary, he highlights significant fortresses in Denmark, Sweden, Poland, Prussia, Livonia, France, England, Italy, and Brabant. Overall, the lists contain 189 strongholds.

The fortresses were almost always fortified cities at key points along various routes. Their locations made them strategic, economic, and political centres, as well as crucial waypoints for merchants, messengers, post riders, journeymen, and fellow travellers — the intended audience addressed by Wintzenberger in his foreword.

For travellers like Samuel Kiechel, large fortified cities offered not only safety but also some comfort. Kiechel passed through perilous lands on his journey, whether due to war or the remoteness of the region, where banditry could go largely unchecked. Fortified cities provided security and the amenities for a traveller to recover from an exhausting journey.

The Reprinted Edition and the Leipzig-Itinerary

Daniel Wintzenberger’s itinerary concludes at this point. But the reprinted edition from 1597 offers additional information. First, there is a compilation of the distances from Dresden to various cities. This list is somewhat curious. The majority of cities are in the Holy Roman Empire. But in between, there are Damascus (481 German miles), Jerusalem (480 German miles) and Lisbon (330 German miles).

Moreover, the reprinted edition presents an inventory of all major trade fairs held across the Empire. This list would be helpful to merchants and travelling artisans.

Heraldry

The next section of the itinerary consists of several pages of blank escutcheons. In heraldry, an escutcheon is the shield on which a coat of arms is displayed. Wintzenberger notes that these blank shields might be useful for apprentices of goldsmiths, sculptors, stonemasons, carpenters, and armourers. The comment is vague, and the purpose of the shields remains unclear.

The final part of the reprinted edition features several pages showing the coat of arms of the Emperor, the Prince-Electors, nobility members, foreign realms and various cities. These visual representations could assist travellers. Heraldic symbols were often displayed on city gates.

The Length of a Mile

Daniel Wintzenberger’s itinerary of Leipzig is mostly a copy of the Dresden itinerary. However, one notable addition is an explanation of the distances. All distances in the itinerary are in miles. But in the early modern period, the length of a mile could differ between countries.

Wintzenberger explains that the German, Spanish, Danish, Swedish, Polish, Bohemian, and Livonian miles are roughly similar in length. The Norwegian, Hungarian and Swiss miles are about one and a half times as long as the German mile. One German mile equals five Italian or two French miles. Five English miles are equivalent to three German miles. Five Russian versts equal one German mile.

The Itinerary — an Early Modern Travel Guide?

Itineraries helped to plan a journey. A traveller could choose a route to a destination, learn the waypoints and distances, estimate the time needed to reach the destination and organise finances and provisions accordingly.

Samuel Kiechel did not mention the use of itineraries, but he might have consulted them in preparation. Our traveller recorded the distance he travelled each day and noted the territorial domain he traversed. Itineraries could have provided such information.

However, while valuable for journeys to certain popular cities, itineraries covered only the main roads. The density of the road network and the available knowledge about it varied across different parts of Europe. Northern Italy, the most developed Renaissance region and popular travel destination, led the way and had already established a network of postal routes. In the German-speaking countries and France, itineraries linking all major cities were available. The more comprehensive itineraries often included additional directions into the neighbouring and, at the time, peripheral regions of Eastern Europe and Scandinavia. Outside Western and Central Europe, itineraries were not in use.

Additionally, itineraries contain the names of places and the distances between them, but do not provide directions. With the lack of road signs in the sixteenth century, a traveller could not quickly identify which ruddy track was the road to his destination.

Kiechel’s journey was not straightforward. He had no fixed list of popular destinations he intended to visit. Our traveller’s route more or less meandered through Europe, visiting regions such as Sweden, Poland, Lithuania and Livonia. While he used major roads described in the itineraries, he would switch between them or go ‘off the beaten track’.

Illustrations & References

All images are in order of appearance with links to sources on external websites:

- Schellinks, Willem, Italiaans landschap, 1637 – 1678; Rijksmuseum Amsterdam.

- Itinerary of the route from Stettin (Szczecin) to Leipzig, in: Mayr, Georg, Wegbüchlin, Augsburg, 1612, fol. 20r; Bayerische Staatsbibliothek.

- Etzlaub, Erhard, Das ist der Rom-Weg von meylen zu meylen …, ca. 1500; Bayerische Staatsbibliothek.

- Wintzenberger, Daniel: Wegweiser oder Reyse Büchlein von der Stad Dreszden, 1597; Martin-Luther-University Halle Wittenberg.

- Itinerary of the route from Dresden to Belgrade, in: Wintzenberger, Daniel: Ein naw Reyse Büchlein von der Stad Dreßden, 1578; Bayerische Staatsbibliothek.

- Bridges across the Rhine and Elbe, in: Wintzenberger, Daniel: Ein naw Reyse Büchlein von der Stad Dreßden, 1578; Bayerische Staatsbibliothek.

- Wintzenberger, Daniel: Wegweiser oder Reyse Büchlein von der Stad Dreszden, 1597; Martin-Luther-University Halle Wittenberg.

- Wintzenberger, Daniel: Ein naw Reyse Büchlein von der Stad Dreßden aus durch gantz Deudschlandt in die andern anstossenden Königreichen und umbligenden Lendern, Dresden 1578. Wintzenberger, Daniel: Wegweiser oder Reyse Büchlein von der Stad Dreszden, Dresden 1597. ↩︎

- Wintzenberger, Daniel: Ein Naw Reyse Büchlein von der Weitberümbten Churfürstlichen Sechsischen Handelstad Leiptzig, Dresden 1595. ↩︎

- The Empire was an elective monarchy and the privilege to elect a future King and Emperor was held solely by seven Prince-electors: the Archbishops of Cologne, Mainz and Trier, the Duke of Saxony, the Margrave of Brandenburg, the King of Bohemia and the Count Palatine. ↩︎

- One German mile is about 7400 metres or 7.4 kilometres. ↩︎