“On 25 May, the day of St Urban, the raft arrived at lunchtime in Ingolstadt in the Duchy of Bavaria. I left the raft because various strange rows and fights had broken out on board, and stayed in the inn of Iheronimus Satler for two nights.“1

To Regensburg

25 May – 28 May 1585

Samuel Kiechel had left his hometown of Ulm, said goodbye to his parents in Lauingen and was now on a raft down the Danube to Regensburg. A leisurely cruise down the river sounds like the ideal start to a long journey. How much comfort could be found on a raft is questionable, but it undoubtedly beat trudging along on foot on a dirt road in the early summer’s heat. The Danube’s banks would have been lush and green, with the river still following its natural course without much human interference.

Neuburg and Ingolstadt

Samuel Kiechel left Lauingen and went to Höchstädt on the Danube. He caught up with the raft he had left the previous evening and went on board. The raft travelled down the river past Donauwörth and onwards to Neuburg, where it arrived in the afternoon. According to our traveller, Neuburg was the residence of Philip Ludwig II, Count Palatine of Neuburg.

The Duchy of Neuburg was one of a confusing myriad of territorial entities that made up the Holy Roman Empire. Unlike other states in early modern Europe, all efforts to centralise the Empire had failed, and it had remained a patchwork of large and small territories and free cities. The Duchy of Neuburg came into existence in 1569 after the Duchy of Palatinate-Neuburg, itself only just established in 1505, was partitioned between the five sons of the Duke.

After spending the night in Neuburg, the raft continued down the Danube to Ingolstadt in the Duchy of Bavaria. However, the journey was not without its challenges. Various disputes and brawls had arisen among the passengers, making Samuel Kiechel feel too uncomfortable to stay on board.

Our traveller did not tell us what happened. We do not know if he was directly involved in any brawls or if the atmosphere was threatening enough to make him leave. With the description of the passengers in mind (Anabaptists, Jesuits, Martinists and Papists), the disputes could very well have been about religion. Whatever the reason, Kiechel changed his plans rather than continue his journey on the raft. He had not yet developed the thick skin of a seasoned traveller to ignore the discomfort. He spent the night in Ingolstadt in the inn of Hieronimus Satler.

Kiechel rarely mentioned the names of people he met. Hieronymus Satler and the raftsman Marte Clonz, whom he had mentioned earlier, are two rare exceptions. Without substantial research in local archives, it is impossible to say anything about either man’s background. But they were somehow known to our traveller, who would otherwise not have mentioned their names.

One link connecting these men was the Danube. In a time when news about the world relied on people physically carrying it from place to place, either in written form or as word-of-mouth, knowledge of places and people was primarily focused along the main traffic links. One of the largest and oldest links was the Danube. Raftsmen like Marte Clonz, as well as merchants, messengers, and other travellers, arrived daily on the river, bringing news and stories. Along this line of communication, cities like Ulm, Ingolstadt and Regensburg were directly connected. The inn of Hieronymus Satler could have been a place with a good reputation or the house where visitors from Ulm would usually stay. Soon, Samuel Kiechel would leave the Danube. His journey into the world outside his familiar horizons began at that point.

After one night in Ingolstadt, our traveller found a boat that took him further downriver on the Danube to the imperial city of Regensburg.

Philipp Apian’s Map of Bavaria

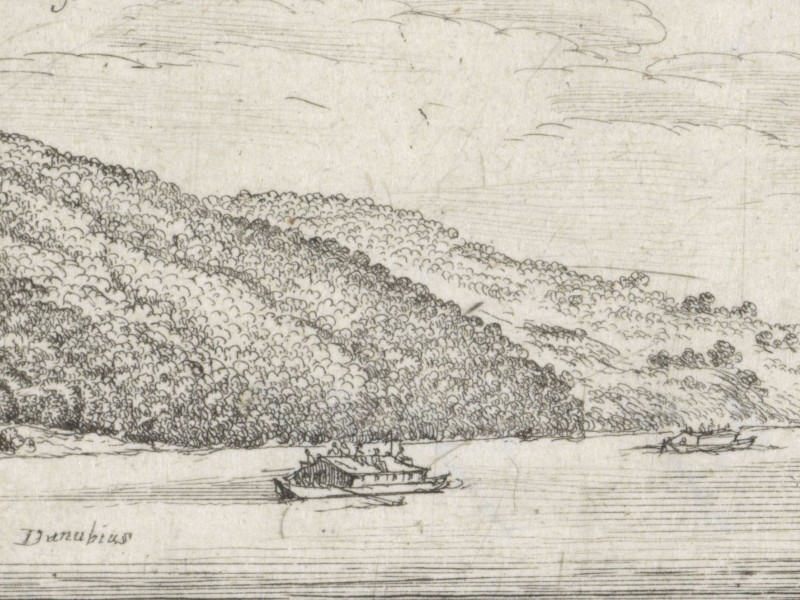

A journey on the Danube in the sixteenth century was different from today. The river was not yet hemmed in by artificial embankments and segmented by dams and locks. It meandered through the countryside with floodplains and riparian woodlands on both sides.

As the longest river in central Europe, the Danube has been a vital artery for trade, transport, and communication since ancient times. It served as a lifeline, connecting the territories between its source in southern Germany and the Black Sea, facilitating the flow of trade goods and the exchange of news and ideas.

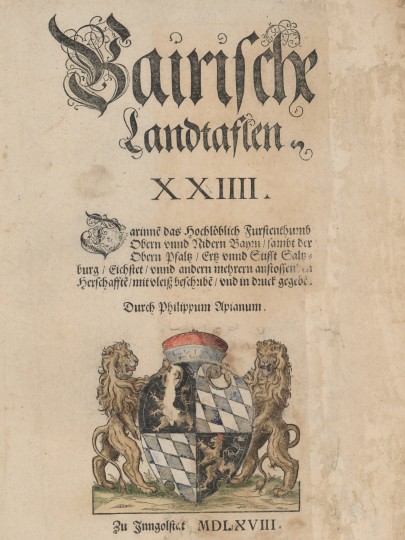

Title page of Philipp Apian’s “Bairische Landtaflen“, 1568

The “Bairische Landtaflen” (Bavarian regional maps)2 presents a view of the Danube and the landscape Samuel Kiechel travelled through. The “Landtaflen” are 24 large-scale maps that, put together, show the Duchy of Bavaria. In 1554, the Bavarian mathematician Philipp Apian (1531-1589) received the commission to make the map for Duke Albrecht V. Apian surveyed various parts of the Duchy in the following seven years. He finished his work in 1563 and presented his map to Duke Albrecht. Apian’s original regional map was a unique single print stored in the Duke’s library. It was destroyed in 1782.3

Fortunately, the Duke had ordered Apian to prepare the map for publication. The engraver Jost Amman had copied and then divided the map into twenty-four large-scale segments. The individual parts were printed and published in 1568. The resultant large-scale regional tables were of unusually high quality for their time and would only be surpassed in the nineteenth century.4

The Danube from Donauwörth to Ingolstadt in the “Bairische Landtaflen“, 1568

Kiechel’s hometown of Ulm is not found on the “Bairische Landtaflen” as it was not part of the Duchy of Bavaria. But Neuburg, Ingolstadt and Regensburg can be seen. A small table with a selection of symbols helps to differentiate cities and villages. The symbols also indicate if a place has a market, a palace, is an imperial city or belongs to a diocese.

On the maps, the Danube is depicted as a leisurely flowing river. Besides the towns and cities, many forests and smaller rivers are visible. But the roads are missing. Due to this lack of notable infrastructure, the rivers, especially the Danube, give the impression of highways crossing the Duchy.

Samuel Kiechel’s journey down the river led past many small towns and villages. The hilly and forested landscape north of the Danube between Donauwörth and Regensburg was the mountain range of the Franconian Jura. On the southern bank, our traveller would have seen low hills and, between Neuburg and Ingolstadt, the fenland of the Old Bavarian Donaumoos.

The Imperial City of Regensburg

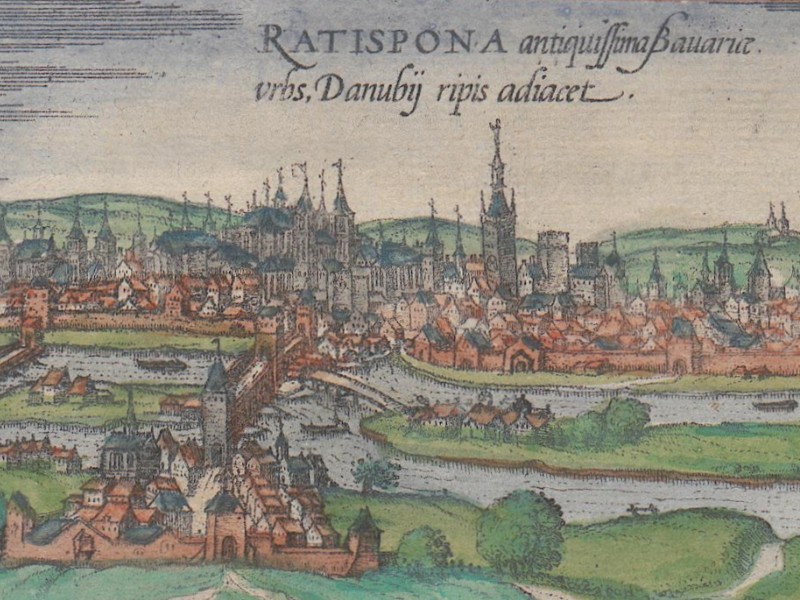

Regensburg, 1572

Downriver from Ingolstadt, the Danube turns toward the northeast and reaches its northernmost point at Regensburg. Arriving in the city by boat, Samuel Kiechel’s first sight would have been church towers, the two large islands in the Danube, and the stone bridge connecting both sides of the river.

Regensburg is in Bavaria. Today, it is known for its well-preserved medieval Old Town and the Regensburg Cathedral. The Romans founded Regensburg as a military fort in 179 CE at the northern border of their Empire. Soon, this fort attracted settlers and evolved into a town. Regensburg became a significant trade hub in the Middle Ages with its advantageous location on the Danube. The city’s strategic importance was further consolidated when it became a free and imperial city in 1245.

Most towns and cities in the Holy Roman Empire were under the rule of local lords and territorial princes. Those cities had a degree of autonomy within their walls. But there was always the possibility of their lord exercising his authority. In contrast, imperial cities like Regensburg or Ulm were only subordinate to the Emperor. These cities were usually wealthier, had political influence and, like Ulm, had often accumulated large territories outside their walls.

Throughout the medieval and early modern period, Regensburg hosted various royal and imperial assemblies, and from 1663 to the end of the Holy Roman Empire in 1806, it was the permanent seat of the Imperial Diet.

This view of Regensburg from 1594 captures the power and wealth of the city. The Danube, the two islands and the medieval stone bridge form the foreground, while the massive bulk of Regensburg Cathedral dominates the city’s skyline. More church towers, the town hall and monasteries rise above the sea of rooftops. The legend in the lower right corner of the image identifies some buildings, many of which you can still visit today.

The stone bridge across the Danube was built in the twelfth century and still stands today. This bridge was an architectural feat and profoundly influenced Regensburg’s development. River crossings were both commercially and strategically valuable. At the time of its construction, the closest bridges across the Danube were in Ulm and Vienna. Even by the late sixteenth century, when more bridges had been built, the ca. 550 kilometres (ca. 340 miles) between Ulm and Vienna still featured only nine large stone bridges. This scarcity made Regensburg a crucial link in the trade routes between northern Germany and Italy.5

The bridge across the Danube transformed Regensburg into a bustling commercial hub where river trade intersected with the roads along the north-south axis between northern Germany and Italy. Stadtamhof, the town on the north bank of the Danube opposite Regensburg, illustrates the importance of this river crossing. Today, it is a municipal district of Regensburg, but it was a separate town until 1924. For most of its history, the Dukes of Bavaria ruled it. Due to its strategic location at the other end of the bridge, Stadtamhof was a constant source of tension for Regensburg’s citizens, who repeatedly sought to incorporate it into their city.

Samuel Kiechel spent the 28 May in Regensburg. He did not mention if he visited any of its sights. He spent the day looking for an opportunity to continue his journey. Our traveller was leaving the Danube behind and needed to find companions, transport or a guide to his next destination.

Illustrations & References

All images are in order of appearance with links to sources on external websites:

- Hollar, Wenceslaus, Landschap met gezicht op slot Rannariedl aan de Donau, 1625 – 1677; Rijksmuseum Amsterdam.

- Anonymous, Boeren vechten voor een herberg, 1630 – 1698; Rijksmuseum Amsterdam.

- Philipp Apian, Chorographia Bavariae — Bairische Landtaflen. XXIIII. Ingolstadt 1568; Bayerische Staatsbibliothek.

- Philipp Apian, Chorographia Bavariae — Bairische Landtaflen. XXIIII. Ingolstadt 1568, map 9, Bayerische Staatsbibliothek.

- Regensburg, in: Braun, Georg, Hogenberg, Frans: Civitates Orbis Terrarum (1), Cologne 1593, fol. 40v; Heidelberg University.

- Regensburg, in: Braun, Georg, Hogenberg, Frans: Civitates Orbis Terrarum (5), Cologne 1599, fol. 51v; Heidelberg University.

- Die Reisen des Samuel Kiechel aus drei Handschriften, K. D. Haszler (ed.), Stuttgart 1866, p. 2; Bayerische Staatsbibliothek. ↩︎

- Philipp Apian, Chorographia Bavariae — Bairische Landtaflen. XXIIII. Ingolstadt 1568; Bayerische Staatsbibliothek. ↩︎

- Meurer, Peter H.: Cartography in the German Lands, 1450–1650, in: Woodward, David: The History of Cartography, Vol. 3, Pt. 2, Cartography in the European Renaissance, pp. 1223-1224; Hartner, Willy: Apian, Philipp, in: Neue Deutsche Biographie 1 (1953), p. 326. ↩︎

- Meurer: Cartography in the German Lands, pp. 1223-1224. ↩︎

- Wintzenberger, Daniel, Ein naw Reyse Büchlein von der Stad Dreßden aus durch gantz Deudschlandt in die andern anstossenden Königreichen und umbligenden Lendern, Dresden 1578, chp. LXXI. ↩︎