“When they were three miles outside the city, they encountered sixty bandits. The brigands had hidden in the shrubbery, spied on the convoy, and opened fire straight away. All soldiers and four of the carters were killed.”1

From Antwerp to Aachen

10 December – 13 December 1585

Route from Antwerp to Aachen

While travelling through the Low Countries, Samuel Kiechel was repeatedly anxious about ambushes and bandits. So far, the fear had not materialised. Our traveller arrived safely in Antwerp and stayed there for a few days to recover and seek new companions.

During the next stage of his journey, from Antwerp to Cologne, the threat grew more immediate. The route ran close to the frontlines between the Spanish Netherlands and the Dutch Republic. Furthermore, it was now December, and winter had worsened the already rough condition of many early modern roads.

Mechelen

After spending several days in the occupied city of Antwerp, Samuel Kiechel departed. He planned to return to Germany, with Cologne as his destination. He and his new companions, four merchants and a messenger, travelled four miles to Mechelen.

Kiechel does not provide any details about Mechelen; however, it is worth noting the excellent view of the city drawn by Anton van den Wijngaerde, which is available in the digital collection of the Ashmolean Museum in Oxford. As is typical of his style, van den Wijngaerde depicts the city in profile. The image appears very lifelike, especially as one of the gates of Mechelen and the activity around it are prominently featured in the foreground. The houses surrounding the gate and the traffic on the road suggest how this place might have appeared to a traveller like Samuel Kiechel.

A profile view of Mechelen is also included in volume one of the “Civitates Orbis Terrarum”.

Mechelen, 1572

While both images offer a glimpse of how the city may have looked in the past, by the time of Kiechel’s visit, it had become a victim of the war. In 1572, Mechelen was captured and looted by a Spanish army. Eight years later, in 1580, it was taken by a combined Dutch and English force. After taking control, the English mercenaries ransacked the city again. In July 1585, just months before Kiechel’s visit, Mechelen was retaken by a Spanish army under the command of Alessandro Farnese, Duke of Parma (1545-1592), who had also captured Antwerp. Like Antwerp, discipline among the soldiers was strict, and the city was spared a third sacking.

Samuel Kiechel and his companions spent the night in Mechelen. Before they left the city the following day, they inquired about the dangers on the road to Maastricht. According to our traveller, Mechelen was only four miles from Bergen op Zoom, and Dutch raiding parties regularly made incursions into this area.

The war between the independent Dutch provinces and the Kingdom of Spain was fought not only through large battles and sieges but also through minor incursions and raids. The mercenaries and soldiers of both sides did not particularly care whether their victims were soldiers or civilians, Dutch, Spanish, or uninvolved travellers. In fact, travellers often promised more loot than the local population did. Such ambushes and robberies were common enough to be depicted in contemporary Dutch art.

Now that Kiechel was travelling through the Spanish Netherlands, he needed to be cautious of Dutch ambushes. Especially with both Antwerp and Mechelen taken by Spanish forces just months earlier, the area around both cities was dangerous, with groups of Dutch mercenaries and raiding parties waiting for an opportunity to retaliate in some manner.

By asking around, Kiechel and his companions learnt that the previous day, a merchant convoy from the German region of Hesse had arrived in Mechelen. The convoy consisted of forty-eight horses and carried grain, wine and other foodstuffs. The merchants sold their cargo and left the city in the evening. Seventeen soldiers accompanied the convoy as an escort for the return journey. Three miles outside of Mechelen, a group of sixty armed men ambushed the merchants. The bandits had watched the convoy approach and opened fire immediately. Most of the escorting soldiers and four carters were killed, and the others were captured and taken to Bergen.

Upon hearing this story, Samuel Kiechel and his companions were worried that the same fate might befall them. They discussed their options. One of them, a messenger from Aachen, urged the others not to wait and argued that after the recent attack, the bandits would have left the area. The group eventually agreed to take the risk and continue their journey along the planned route.

Ambush!

When they left Mechelen the next morning, they found a group of armed soldiers on horseback at the gate. Kiechel counted sixty horses. The soldiers were waiting for the governor of the city, who was heading in the same direction as the travellers. Instead of leaving on their own, Samuel Kiechel and his companions decided to wait for the governor and ask if they would be allowed to travel with him.

When the governor arrived, he turned out to be Italian. Consequently, the Italian merchant in Kiechel’s group was sent to approach him. The governor accepted the request, and the travellers were permitted to join him and his soldiers. It soon proved to be a wise decision.

The travellers and soldiers left Mechelen. When they approached the spot where the German merchants had been ambushed the previous day, a trumpeter was dispatched to ride ahead as a scout. Soon after, he spotted people hiding in the bushes along the road and blew his trumpet. When the governor’s soldiers heard the signal, they charged forward.

However, the road was deep and flanked by trees and thick undergrowth on both sides. The surrounding area was soggy, making it difficult for the horses to advance. The soldiers dismounted and attacked on foot, but they could not catch any of the people hiding in the bushes. The bandits fled, leaving behind hats, guns or provisions. One of them fired a shot at the soldiers but missed. In the evening, the governor received the message that twenty-four bandits had been involved.

After this encounter, Kiechel pondered what might have happened if they had left Mechelen by themselves, as one of his companions had suggested. With only six men and just three guns among them, they would not have escaped the ambush.

When the bandits had fled, the governor of Mechelen, his soldiers and the travellers continued their journey and arrived in Diest after nightfall. Despite the late hour, the guards had kept the town’s gates open in anticipation of the group, and Kiechel and his companions were permitted to enter. They thanked the governor for his protection and parted ways.

Weapons and Travelling

The issue of weaponry must be addressed here. Unlike modern journeys, weapons were a common piece of equipment in the early modern period. Most travellers were armed, with the choice of weapon depending on their social status and financial means, ranging from a knife to larger blades or firearms. The destination and regions along the route influenced how well a traveller was armed. The safety of a road depended on the will and resources of local lords or the towns and cities along the way to enforce it. Generally, war zones or remote, sparsely populated areas were hard to control and required every traveller to carry some form of personal protection.

Kiechel seldom mentioned his weapons. Occasionally, he stated he carried a firearm, but he never gave details. There is also no instance in the journal where he reports having to use his weapon. We do not know if our traveller was already armed when he left Ulm or if he acquired a weapon upon entering a dangerous region.

Distrust in Diest

Upon entering Diest, the travellers retired to an inn. Samuel Kiechel then mentioned that one of his companions was especially glad to have escaped the ambush. The Italian merchant in his company told him that he was a jeweller and carried many valuable pearls and gems with him. He was frightened because he did not speak German and still had a long way to travel, as he wanted to return to Italy. Kiechel wrote that after they arrived in Cologne, the man even showed him his treasures.

Regarding their journey, the innkeeper in Diest advised the group to take some of the governor’s soldiers as escorts. The soldiers were mercenaries and available for hire. Kiechel and his companions were weary of this suggestion. They responded that they would think about it and decide in the morning. Our traveller wrote that they distrusted the advice of the innkeeper and considered the mercenaries too greedy.

Samuel Kiechel did not explain why he distrusted the innkeeper or the mercenaries. The travellers had just been saved from an ambush by those soldiers. But a war zone would certainly breed mistrust among the people, and the loyalty of mercenaries depended on their payment. Marauding bands of mercenaries were not uncommon in the area. It is possible that Kiechel suspected the innkeeper had conspired with the mercenaries to relieve the travellers of their money, either by demanding a high payment or by robbing them the next day.

Leaving the Netherlands

Whatever the reason, the following morning, Kiechel and his companions left the inn very early to avoid any argument with the innkeeper about an escort. However, the quick departure was hindered because the town’s gate was still closed. The group had to wait, and eventually, none other than the innkeeper arrived with the keys. The man was in a foul mood because the travellers had disregarded his advice. After he unlocked the gate, the group hurried away. They worried that the governor’s mercenaries might turn up and demand to be taken as an escort. Kiechel and his companions, therefore, rode the whole day without pause and arrived in Maastricht in the evening.

According to our traveller, Maastricht was at the border between the Holy Roman Empire and the Kingdom of Spain. It was heavily fortified, and the river Meuse divided the city. One part of Maastricht belonged to the King (of Spain) and the other part, across the bridge on the opposite side of the river, belonged to the Bishopric of Liège.

Maastricht, 1575

A profile view of Maastricht is in volume two and a plan view in volume three of the “Civitates”. The name “Traiectum ad Mosam” is found in both images and is the Latin name of the city.

The plan view shows the network of streets of Maastricht and provides a clear impression of the city’s size and fortifications. A few buildings are labelled. The profile view shows the impressive skyline of Maastricht as a visitor might have seen it. Additionally, the view includes a legend with forty-one entries referencing key buildings. In both images, the river Meuse is depicted, dividing the city into the two parts Kiechel mentioned.

Maastricht, 1581

Maastricht was captured by a Spanish army in 1579. Due to its strategic position on the Meuse River and proximity to the Holy Roman Empire’s border, the Spanish retained control of the city for most of the war. In 1632, the Dutch eventually besieged and seized it.

After arriving at Maastricht, our traveller and his companions had to wait at the gate for a lengthy period. The guards asked for their names, places of origin and where they had arrived from. They had to answer the same questions at the inn.

Aachen

The travellers stayed overnight in Maastricht and resumed their journey the following day (13 December). They travelled along a very rough road to Aachen, thirty kilometres to the east.

Kiechel described Aachen as an old and poorly constructed city. It was unfortified and had no river. He wrote that Aachen had hot springs called the ‘keysers badt’ (Emperor’s spa). According to Kiechel, the spa was located behind the town hall. The water from the springs flowed out of the rocks and was very warm. Otherwise, our traveller found Aachen a very dull place.

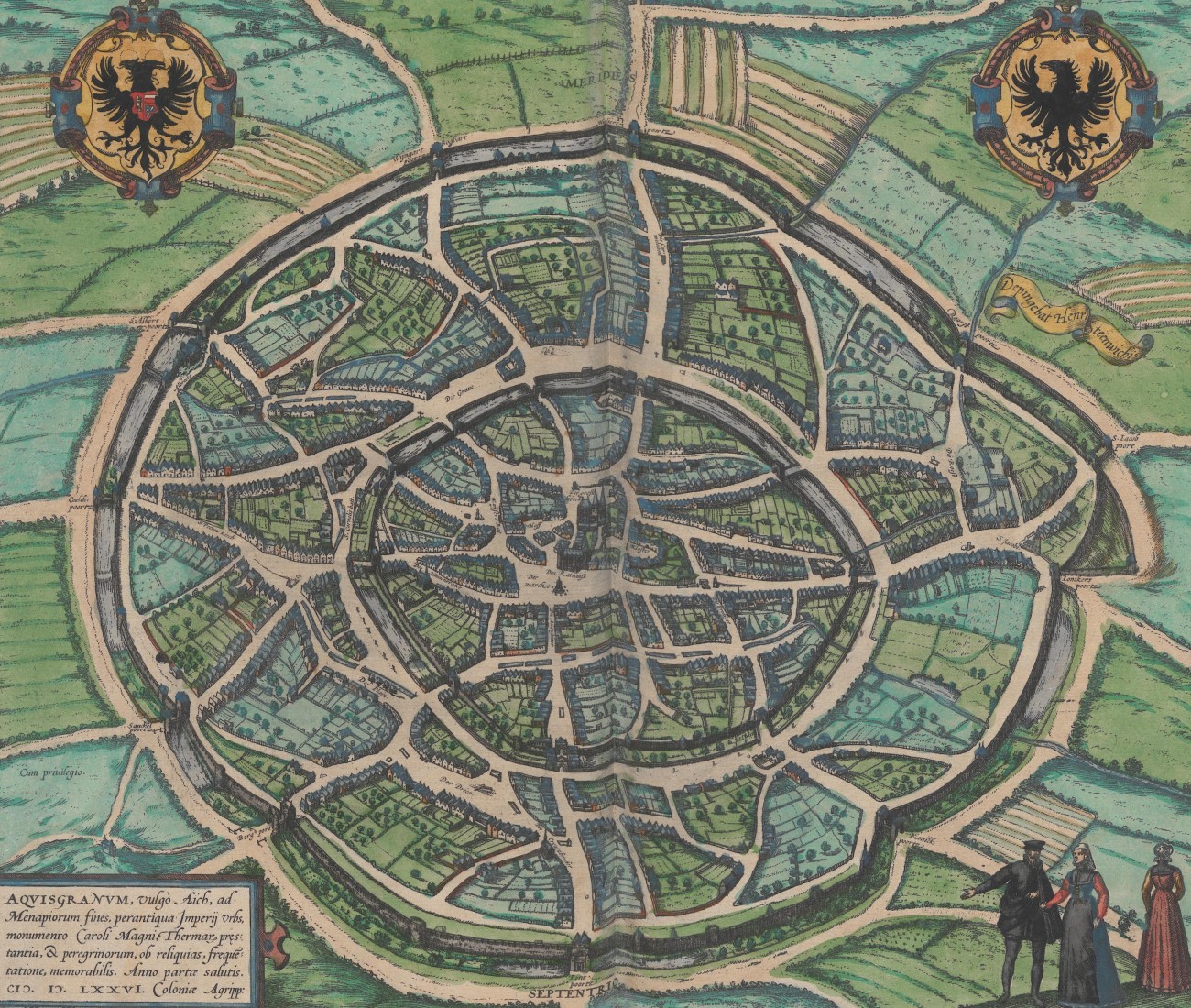

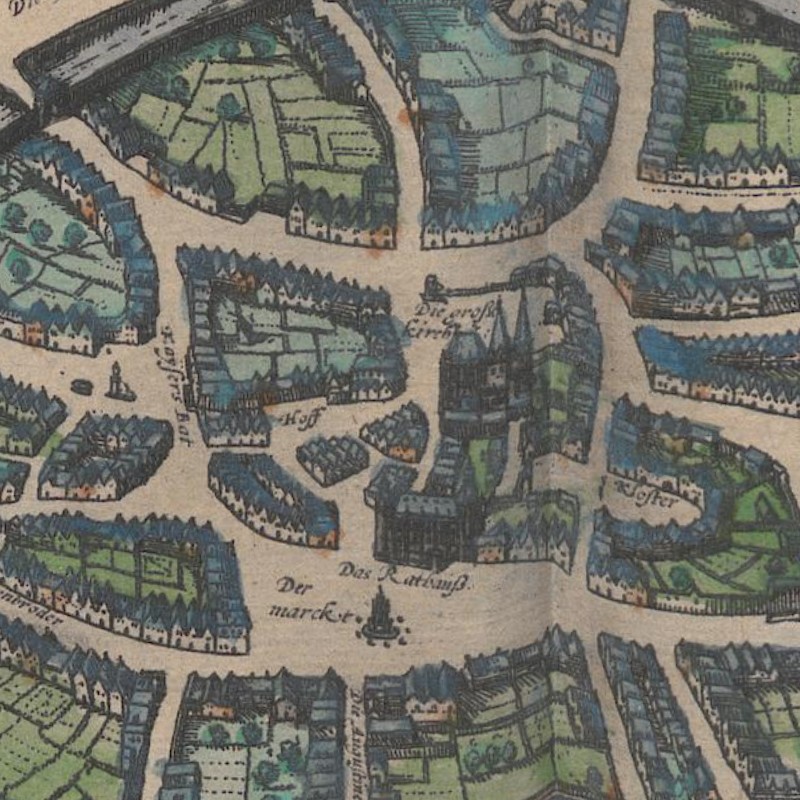

A bird’s-eye view of Aachen is in volume one of the “Civitates”.

Aachen, 1572

The hot springs have been a major attraction in Aachen for many centuries. The place had once been a Roman spa and later became the preferred residence of Charlemagne. From Otto I in 936 to Ferdinand I in 1531, the Kings of East Francia and later the Roman Kings (Holy Roman Empire/Germany) were crowned in Aachen. It became an imperial city in 1166. Although historically significant, Aachen was neither a powerful economic nor a political centre. When Emperor Charles V (1500-1558) abdicated in 1556, he divided the Habsburg domains between his son Philip (Philip II, 1527-1598) and his brother Ferdinand (Ferdinand I, 1503-1564). Philip inherited the Netherlands, which became part of his Spanish Empire. Ferdinand had already been crowned as King of Germany and would later become Emperor. With this division, Aachen became a marginal city on the edge of the Empire, losing its political influence and its role as the site of coronations.

Nevertheless, Aachen had remained a popular spa town ever since. The Emperor’s spa, Kiechel mentioned, was a new bathhouse built around 1540 because the old medieval structure was beyond repair. On the map, the bathhouse is located to the left of the cathedral and the market square.

Emperor’s Spa (“Kaysers bat”), town hall (“Das Rathauß”) and market square (”Der marckt”)

The arrival in Aachen meant that Samuel Kiechel had finally left the conflict zone of the Eighty Years’ War. However, the danger had not entirely passed. The war had spilt over the border, with many Dutch taking refuge in the cities of the Empire, and Spanish armies operating on both sides of the border.

Illustrations & References

All images are in order of appearance with links to sources on external websites:

- van de Velde, Esaias, The Robbery, 1616; Rijksmuseum Amsterdam.

- Ortelius, Abraham, Theater of the World, Antwerp 1587, fol. 30v; Library of Congress.

- Mechelen, in: Braun, Georg, Hogenberg Frans: Civitates Orbis Terrarum (1), Cologne 1593, fol. 18v; Heidelberg University.

- Vrancx, Sebastiaen, Overval op een reiswagen, 1583 – 1647; Rijksmuseum Amsterdam.

- van de Velde, Esaias, Overval op een reiswagen, 1626; Rijksmuseum Amsterdam.

- de Molijn, Pieter, Boomrijk landschap met gewapende mannen, 1620-1630; Rijksmuseum Amsterdam.

- Wouwerman, Philips, Man Loading a Rifle, after c. 1660; Rijksmuseum Amsterdam.

- Maastricht, in: Braun, Georg, Hogenberg Frans: Civitates Orbis Terrarum (2), Cologne 1575, fol. 21v; Heidelberg University.

- Maastricht, in: Braun, Georg, Hogenberg Frans: Civitates Orbis Terrarum (3), Cologne 1593, fol. 15v; Heidelberg University.

- Aachen, in: Braun, Georg, Hogenberg Frans: Civitates Orbis Terrarum (1), Cologne 1593, fol. 12v; Heidelberg University.

- Die Reisen des Samuel Kiechel aus drei Handschriften, K. D. Haszler (ed.), Stuttgart 1866, p. 40; Bayerische Staatsbibliothek. ↩︎