View of Görlitz in the “Civitates Orbis Terrarum”, 1575

What did Samuel Kiechel see on his journey? How can we grasp the impression a city left on our traveller when the places he visited have changed substantially since the sixteenth century?

The answer to this question is the “Civitates Orbis Terrarum”, the first modern city atlas by Georg Braun and Frans Hogenberg. Published in six volumes between 1572 and 1617, the “Civitates” features views of European cities and towns, along with some images of locations in Africa, Asia, and even America. At the time, the authors aimed to present towns and cities of the world to an educated audience for study without the need to leave home. Now, this publication offers a glimpse into Samuel Kiechel’s world — a world that has, in part, vanished due to wars, fires, and modern city planning.

The “Civitates Orbis Terrarum”

The First Modern City-Atlas

The sixteenth century was a time of growing interest in the world beyond an individual’s daily surroundings. Voyages of exploration and colonial expansion sparked curiosity about distant places. Maps, in particular, became a popular way to display the expanding knowledge of the new world and to depict the old world with greater detail and accuracy. Their publication and distribution were promoted by the invention of the printing press, another influential invention of the Renaissance. Maps could be reproduced and printed in large quantities and sold at an affordable price.

A significant development in cartography was the publication of the “Theatrum Orbis Terrarum” in 1570 by Abraham Ortelius. It was the first modern atlas, featuring the best available maps printed in a consistent format and bound in a book with descriptions and references to the mapmakers.

Map of England in the “Theatrum Orbis Terrarum”

However, people were not only interested in the new world or regional cartography but also in detailed knowledge about specific places. Unlike today, where popular travel destinations can range from urban centres to quaint villages, sunny beaches or remote retreats, a sixteenth-century traveller primarily sought to visit cities. Cities were the economic hubs of the time, where increased trade across Europe and the influx of new commodities from colonial possessions had led to growth and prosperity. They also served as centres of social life and, under the influence of the Renaissance, of education and the arts.

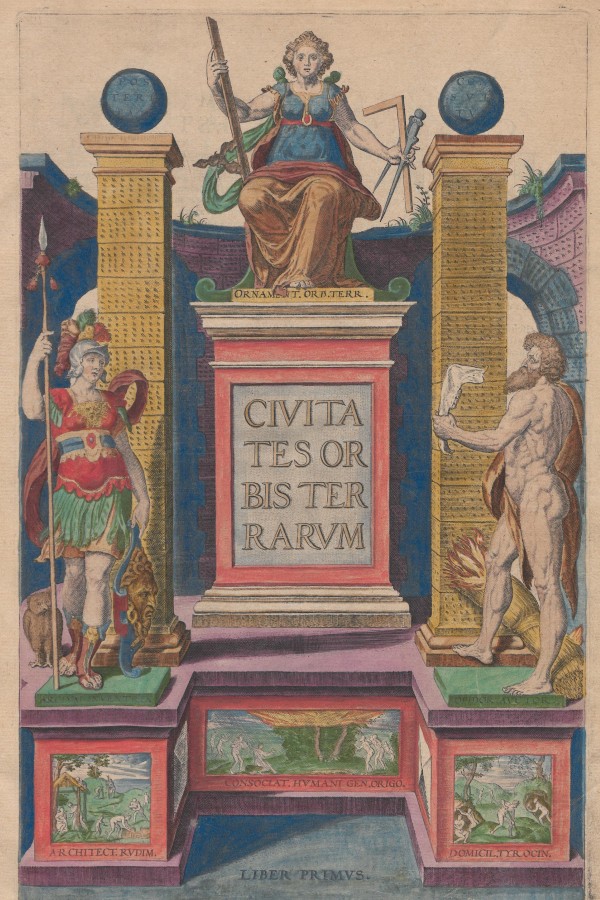

Title page of the “Civitates Orbis Terrarum”

Inspired by the “Theatrum” and initially planned as a supplement to it, Georg Braun and Frans Hogenberg published the “Civitates Orbis Terrarum”. Its first volume was published in Latin in 1572, just two years after Ortelius’ work. At first, its publishers did not plan for more volumes. However, the book was a great success. It was later translated into German (1574) and French (1575) and reissued seven times between 1575 and 1612. Due to its popularity, Braun and Hogenberg decided to continue, releasing five more volumes. The second volume of the “Civitates” was published in 1575, the third in 1581, the fourth in 1588, the fifth in 1598, and the last in 1617. The title “Civitates Orbis Terrarum” was originally only used for the first book. Today, the entire collection is known by this name.1

The Publishers

Georg Braun (1541-1622), a clergyman from Cologne, was the editor of the “Civitates”. He spent two years (1566-1568) in Antwerp as a private teacher to the son of a wealthy Cologne merchant. Antwerp was the cultural centre of the Low Countries. During his time in the city, Braun presumably got to know artists, scholars, publishers, and engravers — contacts that would later prove useful when he set out to publish the “Civitates”.2

Georg Braun’s co-publisher, Frans Hogenberg (1535–1590), was among the leading engravers of maps in the late sixteenth century. Originally from Flanders, Hogenberg had lived in Antwerp but was forced to emigrate to Cologne due to religious tensions. He had worked on many maps for Abraham Ortelius’ “Theatrum Orbis Terrarum” before he began collaborating with Georg Braun on the “Civitates”.

Hogenberg’s work with Ortelius probably inspired the idea of creating a city atlas. Ortelius was actively involved in bringing this idea to fruition. A letter from Georg Braun to the esteemed cartographer, requesting advice on using German place names instead of the usual Latinised versions, exemplifies their cooperation.3

For each volume of the “Civitates Orbis Terrarum”, Georg Braun wrote the foreword and compiled the descriptive texts accompanying each view. He had built a network of contacts to obtain drawings of cities that had not yet been published. In the foreword to every volume, Braun even asked readers to send him images and information about their hometowns. While he directed this call mostly at the educated elites in the cities, it is an early form of public engagement with the publication.

Frans Hogenberg adapted the maps and city drawings supplied by artists and other sources in his workshop to fit the publication before they were engraved and printed.

The “Civitates Orbis Terrarum”

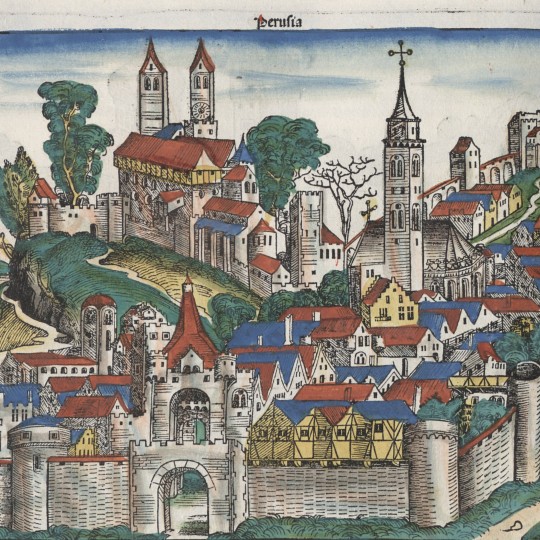

The “Civitates” was not the first collection of city views. However, earlier publications such as the “Nuremberg Chronicle” (1493) by Hartmann Schedel or Sebastian Münster’s “Cosmographia” (1544) focused mainly on textual descriptions and used images solely as illustrations. These authors presented many cities in the form of generic depictions unrelated to reality. For example, in his book, Hartmann Schedel reused some woodcuts multiple times to represent different places, such as Naples and Perugia.4

Conversely, Georg Braun and Frans Hogenberg aimed to publish precise, realistic depictions. The six volumes of the “Civitates Orbis Terrarum” contain images of 475 different towns and cities. In some instances, the collection features two views of the same location, and Rome even has three. When a second view of a city appears, it is usually found in a later volume and a more up-to-date view. While a large number of city views are presented as individual maps, some are arranged to share a page. The extreme case is twelve Swiss cities on a double page in the first volume. Generally, however, between two and five cities share the same page.5

Each view of a city is accompanied by textual information. The texts are usually collations of general information that Georg Braun found in popular chronicles and cosmographies, as well as some contemporary news and details received by letter or oral communication from local sources. However, the maps and city views are rarely described or even mentioned in the texts. Many descriptions mainly focus on the history of the place, the etymology of its name, wealth, and trade.

In contrast to the “Theatrum Orbis Terrarum” with its systematic structure, the “Civitates” appears more random. There is a geographical sequence in all five volumes, starting with the British Isles, Spain and Portugal, then France, the Low Countries, Germany, Scandinavia, northeastern Europe, and finally Italy and the Mediterranean. However, the selection of which cities are shown depended on the images available to the publishers.

A distinctive feature of the “Civitates Orbis Terrarum” is the relationship between text and image. In earlier publications, like Schedel’s “Nuremberg Chronicle”, the text formed a coherent narrative guiding the reader through the volume. The images were merely illustrations. In the “Civitates”, the views and maps take centre stage. The texts provide some additional information, but there is no consistent narrative or order linking the cities.

Presenting European Cities in the Sixteenth Century

A notable feature of the “Civitates” is the variety of visual styles, as different artists contributed to the publication. Some views are top-down, showing the grid of streets in detail, similar to modern maps. Others depict cities from a bird’s-eye perspective, while some present them from ground level in profile view.

The different styles are apparent in a comparison between the images of two of the artists who contributed the most views to the “Civitates”: Georg (Joris) Hoefnagel (1542-1600) and Jacob van Deventer (1500-1575).

View of Angers by Georg Hoefnagel

Hoefnagel had travelled to Spain, Italy, France, England and Germany. During his travels, he drew and sketched numerous cities, with sixty-three of his images published in the “Civitates”. He commonly depicted the places from a low oblique angle, creating bird’s-eye views. Additionally, he integrated them into the surrounding countryside and often added allegorical elements or scenes of local life. However, he kept the city and its immediate surroundings separate. Hoefnagel endeavoured to depict the city as realistically as possible, even when including peripheral scenery.6

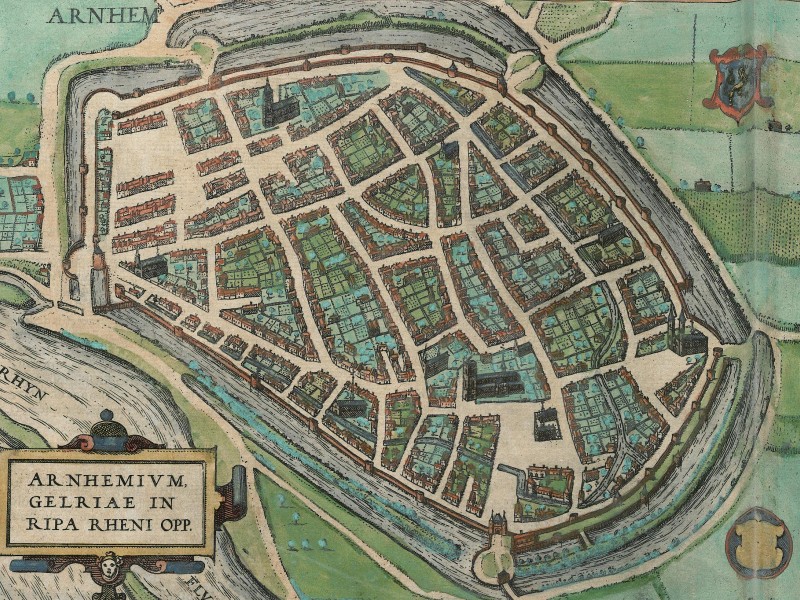

Jacob van Deventer contributed forty-eight images to the “Civitates”. In the service of King Philip II of Spain, van Deventer travelled through the Low Countries, creating maps of all the towns and cities he visited. His views are top-down and resemble modern city plans. He relied on local surveys as the basis for his work. Van Deventer did not embellish his drawings. The views are remarkably accurate representations of a town’s layout. But he did not bother with the buildings. Unlike other views in the “Civitates”, many of his maps show only streets, canals, walls, public buildings, gates, and churches, with features outside the walls such as roads, windmills, canals, rivers, and surrounding minor settlements.7

View of Arnhem by Jacob van Deventer

Van Deventer’s maps were adapted to the style of the “Civitates”, but you can view two notebooks with his drawings in the digital collection of the Biblioteca Nacional de España.

On Costumes and the Turks

One final, intriguing aspect of the “Civitates Orbis Terrarum” is the depiction of people dressed in local attire in the foreground of many views. These figures were not a product of the mapmakers’ imagination; the artists had consulted costume books. The clothing exemplifies regional styles and fashion of the period, and even indicates how Samuel Kiechel might have been dressed.

Example of people in local dress in the “Civitates”

Georg Braun states in his foreword to the “Civitates” that the inclusion of these people was a deliberate decision. The Ottoman Empire was viewed as a threat in the sixteenth century. There was a widespread fear that they might use the published maps to gather strategic information about a city’s defences. To allay this concern, Braun explains they deliberately included the people in each city-view because: “the bloodthirsty Turk, who is not allowed to see printed or painted illustrations, will never allow this book to be seen regardless of its benefits.”8 Muslims were forbidden from viewing images of humans. As a logical consequence, placing people in the foreground or around the edges of maps would prevent the Ottomans from gaining any useful information. It remains uncertain whether this precaution was adequate.

Visiting Sixteenth-Century European Cities

The Hague in the “Civitates Orbis Terrarum“

The images in the “Civitates” depict moats and walls, skyline-dominating churches, and gatehouses that shape the first impressions of a city to any arriving traveller. The bird’s-eye views enable us to see streets and marketplaces, as well as familiar municipal buildings like town halls, and unfamiliar structures such as armouries. Many of the prints also include a glimpse of everyday life. This could be a local scene played out in the foreground, like in Georg Hoefnagel’s images, or simply depictions of boats on a river, carts and people rushing by, or a busy harbour with cargo stacked on the quays.

Despite the desire for realism and accuracy, the city views in the “Civitates” are somewhat biased. Because of its popularity, the publication of a city in this collection served as a form of advertisement. As mentioned, Georg Braun requested contributions from the readers to showcase their city. As a result, many views focus on size, wealth, and strength. The walls, churches, and municipal buildings often form the central features of the images. Sometimes, these structures are depicted more prominently than their surroundings. In many views, the publishers identified important buildings by name or function. Conversely, signs of decay, damage, or low-quality housing of the poor are rarely visible.

In the 400 years since the “Civitates Orbis Terrarum” was first published, wars, natural disasters, and modernisation have greatly altered the appearance of European cities. The “Civitates Orbis Terrarum” therefore provides an invaluable window into the world of the sixteenth century. Samuel Kiechel’s journey took place at the time of its publication, and the cities featured in the collection are as close to Kiechel’s experience of those places as we can get without a time machine.

Illustrations & References

All images are in order of appearance with links to sources on external websites:

- Görlitz, in: Braun, Georg, Hogenberg, Frans: Civitates Orbis Terrarum (2), Cologne 1575, fol. 45v; Heidelberg University.

- England, in: Ortelius, Abraham, Theater of the World, Antwerp 1587, fol. 11v; Library of Congress.

- Braun, Georg, Hogenberg, Frans: Civitates Orbis Terrarum (1), Cologne 1593; Heidelberg University.

- Schedel, Hartmann, Nuremberg Chronicle, 1493, fol. 42v & 48v ; Bayerische Staatsbibliothek.

- Angers, in: Braun, Georg, Hogenberg, Frans: Civitates Orbis Terrarum (5), Cologne 1599, fol. 20v; Heidelberg University.

- Arnhem, in: Braun, Georg, Hogenberg, Frans: Civitates Orbis Terrarum (3), Cologne 1593, fol. 17v; Heidelberg University.

- Rostock, in: Braun, Georg, Hogenberg, Frans: Civitates Orbis Terrarum (5), Cologne 1599, fol. 47v; Heidelberg University.

- The Hague/Den Haag, in: Braun, Georg, Hogenberg, Frans, Civitates Orbis Terrarum (6), Cologne 1618, fol. 9v; Heidelberg University.

- Füssel, Stephan: Natura Sola Magistra — Der Wandel der Stadtikonografie in der Frühen Neuzeit, in: Braun, Georg & Hogenberg, Franz: Civitates Orbis Terrarum — Städte der Welt, Katalog der Stadtansichten (Füssel, Stephan & Althoff, Joahnnes, eds.), Cologne 2015, pp. 58-59. ↩︎

- Ibid., pp. 19-30. ↩︎

- Ibid., pp. 19-20. ↩︎

- Ibid., p. 12. ↩︎

- van der Krogt, Peter, Mapping the towns of Europe: The European towns in Braun & Hogenberg’s Town Atlas, 1572-1617, in: Belgeo 3-4, 2008. ↩︎

- Koeman, Cornelis, Schilder, van Egmond, Marco and van der Krogt, Peter, Commercial Cartography and Map Production in the Low Countries, 1500–ca. 1672, in: The History of Cartography (Woodward, David ed.), vol..3, pt. 2, pp. 1296-1383, see p. 1334. ↩︎

- Koeman, Cornelis and van Egmond, Marco, Surveying and Official Mapping in the Low Countries, 1500–ca. 1670, The History of Cartography (Woodward, David ed.), vol. 3, pt. 2, pp. 1246-1295, see p. 1275. ↩︎

- Braun, Georg, Hogenberg, Frans, Civitates Orbis Terrarum (1), Cologne 1593, Praefatio; Heidelberg University. ↩︎