“The Øresund is no more than one German mile wide, and all ships sailing into and out of the country must lower their sails, drop anchor and pay the toll.”1

From Copenhagen to Helsingborg

3 February – 9 February 1586

After a winter journey by carriage and boat through Denmark, Samuel Kiechel had arrived in Copenhagen. Our traveller wrote that it was much colder in this country than at home (in Ulm/Swabia) because the further someone travelled in Denmark, the further north he would come. Kiechel had heard stories that one winter had been so cold, the sea had frozen over, and people could travel from Copenhagen across the ice on the Øresund to Malmö. He mentioned that the Øresund was usually very rough, and it must have been very cold for it to freeze over.

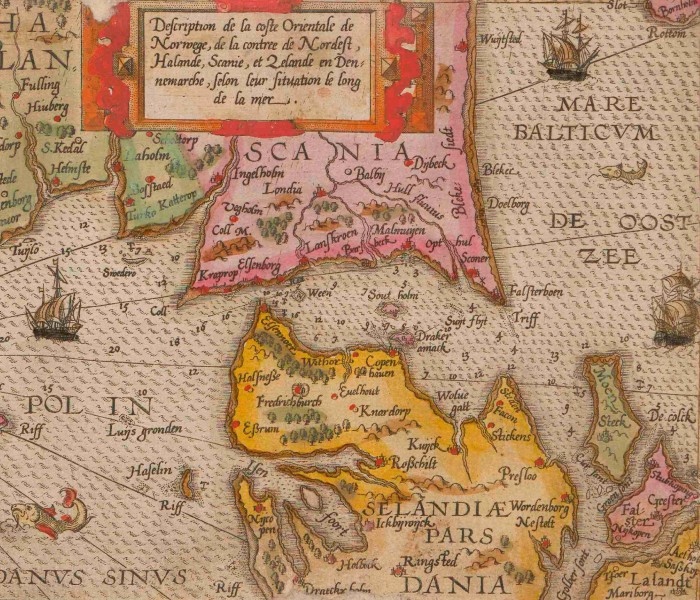

The Øresund is one of the three large straits connecting the Baltic to the North Sea. The other two are the Little and Great Belt, which our traveller had crossed in the previous days. The Øresund, the easternmost of the three, separates the Danish island of Zealand from the Swedish province of Scania. Historically, it was the most important and most frequented of the three sea lanes. The Danish kings have levied a toll (Sound Toll) on ships using the Øresund since the Middle Ages.

In Copenhagen

Samuel Kiechel’s observations of Copenhagen are typically brief. He wrote that the city was the capital of the Kingdom of Denmark. It was not very large and lacked fortifications. The King of Denmark had his residence there, but the palace could be mistaken for a fortress. Copenhagen had a very deep harbour that allowed even large, heavily loaded ships to anchor. At the time of Kiechel’s visit, all vessels in the harbour were trapped in the ice. Eight large ships belonging to the king were anchored close together near the palace.

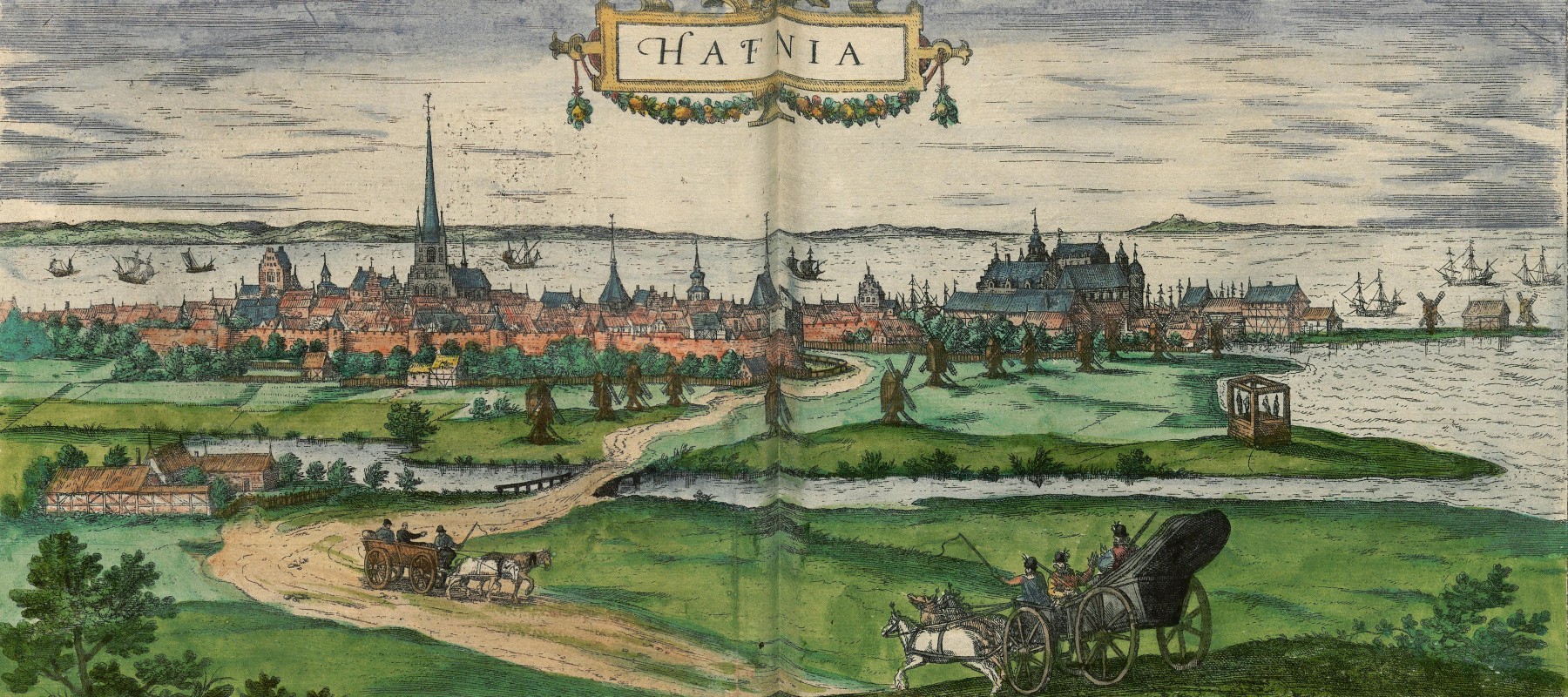

Two views of Copenhagen appear in volume four of the “Civitates Orbis Terrarum”. Both images are profile views and are on the same page. One view shows Copenhagen from the land. In the foreground, there is a farm and a few windmills. In the background, behind the city’s silhouette, are the Øresund and, on the horizon, the coast of Scania. In the foreground of this view are two carriages. One is a peasant’s cart leaving the city, and the other is approaching Copenhagen, seemingly the coach of a wealthy individual. Both vehicles suggest the different modes of transportation available to our traveller.

The city’s silhouette has two focal points: the Church of Our Lady and the royal palace. Kiechel’s remark that the palace looked like a fortress is fitting. It was originally a castle built in the late Middle Ages to defend the harbour. By the mid-fifteenth century, it had become the residence of Danish kings. Neither the church nor the palace still exists. The Church of Our Lady was destroyed by fire in the eighteenth century. The old palace was demolished and rebuilt several times over the centuries. Today, the site is occupied by Christiansborg Palace, constructed in the early nineteenth century.

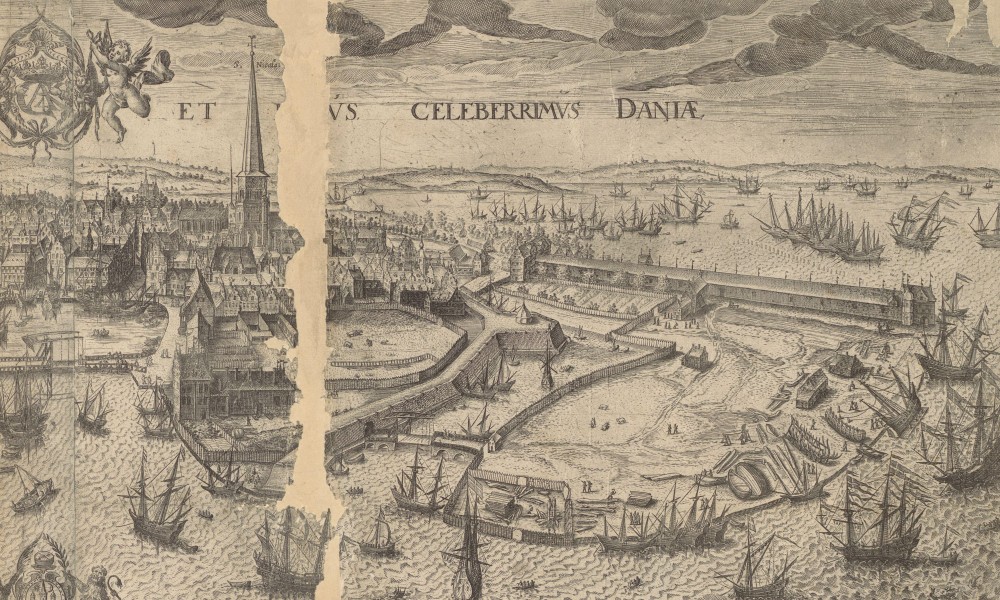

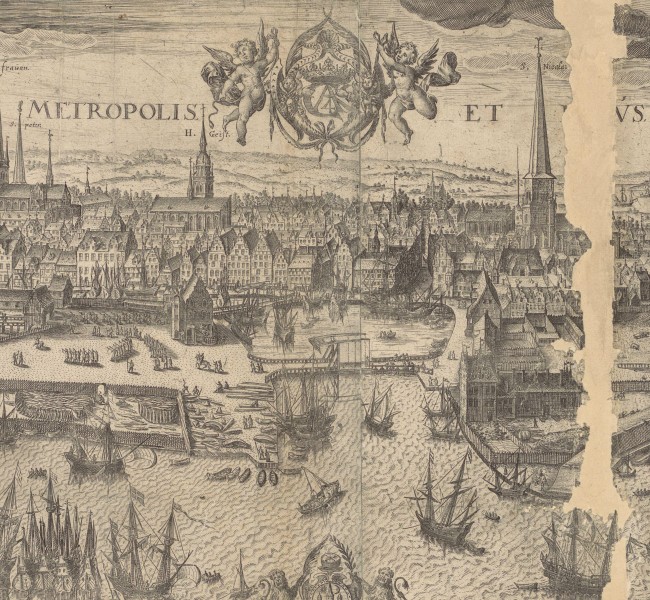

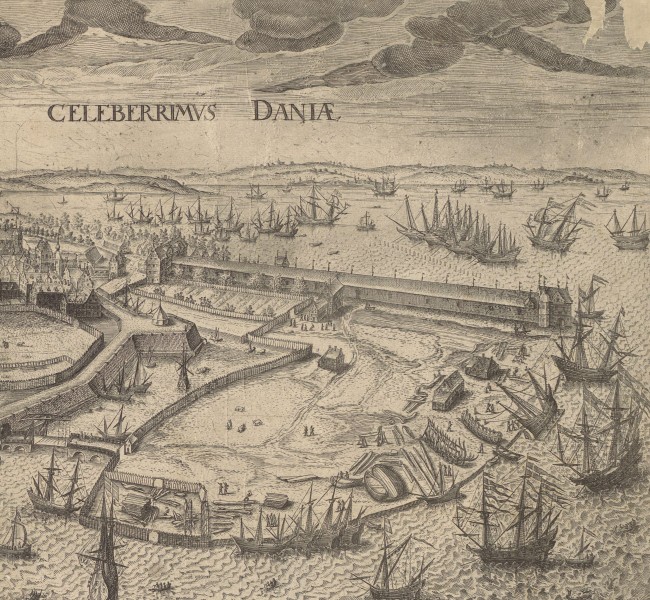

The second image depicts the city from the Øresund. The narrow strips of land in the foreground are islands close to the coast that offer some protection to Copenhagen’s harbour from the sea. The city appears relatively small, just as Kiechel described. Its significance as a major trade centre on the Øresund is highlighted by numerous large ships either anchored or at sea in both images. The palace and the Church of Our Lady are also visible.

An alternative view of Copenhagen from the early seventeenth century provides a more detailed depiction of the city. In this view, the harbour is in the foreground and the Øresund on the right. Both are filled with many ships. On the right is also a shipyard. On the far left side of the image is the Arsenal of Copenhagen, built in 1604. The palace is behind and to the right of the Arsenal, with the Church of Our Lady and other smaller churches situated in the background. Additionally, compared to the images in the “Civitates” and Kiechel’s comments, Copenhagen is now surrounded by fortifications.

Travel Plans

Samuel Kiechel spent five days in Copenhagen. Having reached the city, he had to consider how he should proceed. He could not leave by ship because it was the middle of winter and the sea was frozen. But he was also not in the mood to return to Germany along the same route he had arrived.

Our traveller stayed in the house of a man called Hanns Runckh. Runckh had been born in Hamburg and spoke German. In the same house, two merchants from Lübeck took their accommodation. Both men had businesses and warehouses in Sweden and wanted to travel to Stockholm. Kiechel inquired about them and learnt that both men had a good and honest reputation. So, our traveller approached the merchants and asked if he could join them and travel to Stockholm. The two men agreed, and Kiechel mentioned that they would prove that their good reputation was well deserved.

To Helsingør

At noon on 8 February 1586, Samuel Kiechel left Copenhagen in the company of the two merchants he had met in the city. They travelled in the back of a cart north along the coast of the Øresund. The weather was freezing, and a strong northerly wind cut into their faces. Kiechel was worried that he might suffer frostbite on his nose or ears. This worry was based on stories our traveller had heard from his innkeeper in Copenhagen. The man had told him that he had once travelled from Bergen in Norway in the winter in the company of fourteen other people. Only six of the travellers brought their ears back home, while all the others suffered from frostbite due to the cold and wind.

Kiechel and his companions arrived in Helsingør in the evening. According to our traveller, it was a small and unfortified town by the sea. The sea was called the Sound (Øresund). Castle Kronborg had been built there by the current king, Frederick II. The castle was fortified with mounted guns and garrisoned by many soldiers.

The Sound Toll

The Øresund was the most important shipping lane for trade between the Baltic and the North Seas. A toll (Sound Toll) collected in Helsingør was levied from all ships passing through the Sound. This toll was the single largest source of income for the Kingdom of Denmark for many centuries. It was introduced in the fifteenth century (1429) and abolished in 1857. Toll collection was also enforced in the Great Belt and the Little Belt — the only other routes available.

A navigational chart from the sixteenth century shows the Øresund and the surrounding coastlines in detail. The chart is oriented towards the east and depicts the eastern coast of the Sound from southern Norway to the province of Scania. It contains detailed information about water depths, natural hazards and safe anchorages.

Naval chart of the Øresund, 1596

The toll and the traffic on the Sound interested Samuel Kiechel. He wrote: The Øresund is no wider than one German mile, and all ships entering and leaving Denmark must stop and pay a toll. Our traveller further explains: A vessel carrying grain, salt, herring or similar goods must pay half a Reichsthaler per ’Last’. Ships without cargo, only carrying ballast, still had to pay a quarter of a Reichsthaler per ‘Last’. According to our traveller, it was a hefty toll.

A Reichsthaler was a standard silver coin introduced in the Holy Roman Empire in 1566. It was accepted outside of the Empire, especially in trade between northern German cities and Scandinavia. Samuel Kiechel often used currencies he was familiar with to communicate the value of things.

A ‘Last’ was a unit of weight and volume used in the Middle Ages and early modern period to estimate the carrying capacity of ships. One ‘Last’ was approximately 2000 kilograms in weight or about 2.7 cubic metres in volume.

Kiechel further reports: In good weather, more than fifty to sixty ships often pass through the Sound in a single day. These ships come from Holland and sail to Danzig (Gdańsk) to pick up grain. Despite sailing empty, they must lower their sails and pay the toll. It is easy to see that the toll is the primary source of income for the Kingdom of Denmark, because all ships heading to Sweden, Finland, Narva, Rügen (Island of Rügen), Reval (today: Tallinn), Königsberg (today: Kaliningrad), Danzig (Gdańsk), Stettin (Szczecin), Stralsund, Greifswald, Rostock, Wismar and Lübeck must pass through the Øresund. All ships sailing westward, towards the Netherlands, France, England, Spain and Portugal, also need to pass through the Sound.

About control of the Sound, Samuel Kiechel noted: Directly opposite Helsingør is a village with a castle on a hill above it. This is Helsingborg. No ship can safely sail through the Sound as the mounted guns of both castles can fire all the way to the opposite coast. It is not advised for ships to sail under full sail through the Sound. During the summer, royal Danish ships are present. They are armed with guns and ammunition and carry soldiers and sailors. These royal ships must be ready to raise anchor at any moment. Therefore, no other vessel can pass through the Øresund without paying the toll.

Views of Helsingør and the Øresund

Helsingør, 1598

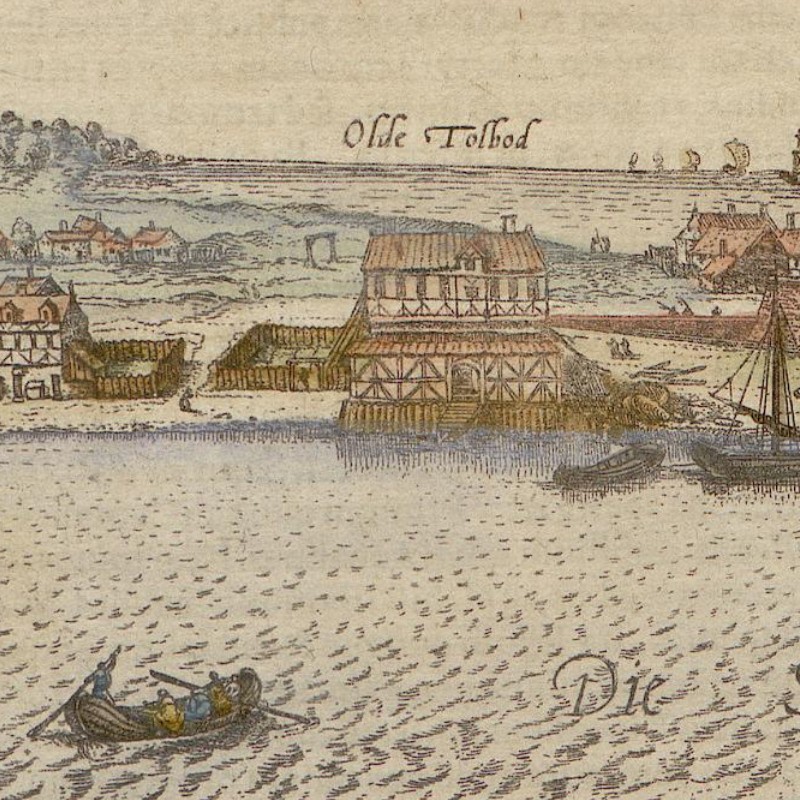

A view of Helsingør is found in volume five of the “Civitates Orbis Terrarum”. The town is depicted from the east with the Øresund in the foreground. Kronborg Castle appears on the right side of the image. Helsingør is positioned in the centre-left and is shown as a small town. Two churches are highlighted by their names. They are both called “Deutsche Kirch” (German Church), which is likely an error by the mapmakers. The largest church in Helsingør is St. Olaf’s Church. The other, smaller church, marked as “Deutsche Kirch” on the map, might have been built by German merchants who settled in Helsingør.

Between the town and Kronborg Castle stands a large house at the edge of the Sound named “Olde Tolbod” (Old Tollhouse). Presumably, ships had to stop here and pay the toll. Three ships are shown in the foreground: two at anchor, and a small rowing boat moves towards the toll house.

A bird’s-eye view of the entire Øresund from the west appears in volume four of the “Civitates”. At the centre of this image is Kronborg Castle, whose location dominates the Sound. Its significance in controlling traffic across the Sound is strongly highlighted. Around Kronborg, over forty large ships are visible; many are anchored on both sides of the castle, likely stopping to pay tolls. Some gunfire is also seen: two ships are firing their guns, along with a single shot from Kronborg. These shots could be gun salutes or might have been fired to emphasise Kronborg’s control over the traffic in the Øresund.

Øresund, 1588

Below Kronborg is the town of Helsingør, and in the lower right corner of the map, a small part of Copenhagen (“Hafniae pars”). Across the Sound from Kronborg, the village and castle of Helsingborg are depicted. Towards the right side of Helsingborg (south), along the coast of the Sound, are the cities of Lund (Landeskron) and Malmö (Elbogen).

A view of Helsingborg is also included in the “Civitates”, but upon closer inspection, it is the same as its depiction in the view of the Øresund. Either the separate view of Helsingborg was made by copying part of the Øresund view, or the other way around.

Samuel Kiechel and his companions were fortunate as a boat left Helsingør to cross the Sound the following day. Kiechel mentions that during winter, travellers often have to wait three or four days for a vessel to Helsingborg because of the ice. He explains: The Øresund is very narrow at this point and filled with ice, but it does not freeze over completely. When the wind blows towards the sea, it pushes the ice out of the Sound, but when it blows towards the land, the ice is pushed back in. There is rarely a moment without wind, so crossing the Sound is always dangerous.

The travellers faced this difficulty navigating through the ice of the narrow Sound. If the wind had shifted and blown towards the land, they might have become stranded with no way to reach either side. Fortunately, the weather remained stable and the travellers safely reached Helsingborg.

Illustrations & References

All images are in order of appearance with links to sources on external websites:

- Copenhagen, in: Braun, Georg, Hogenberg Frans: Civitates Orbis Terrarum (4), Cologne 1594, fol. 28v; Heidelberg University.

- van Campen, Jan Diricks, Gezicht op Kopenhagen, 1570 – 1622; Rijksmuseum Amsterdam.

- Waghenaer, Lucas Jansz., Thresoor der zeevaert, inhoudende de geheele navigatie ende schip-vaert vande Oostersche, Noordtsche, Westersche ende Middellantsche Zee, met alle zee-caerten daer toe dienende …, Amsterdam 1596, fol. 116v; Utrecht University Repository.

- Helsingør, in: Braun, Georg, Hogenberg Frans: Civitates Orbis Terrarum (5), Cologne 1599, fol. 33v; Heidelberg University.

- Øresund, in: Braun, Georg, Hogenberg Frans: Civitates Orbis Terrarum (4), Cologne 1594, fol. 26v; Heidelberg University.

- Die Reisen des Samuel Kiechel aus drei Handschriften, K. D. Haszler (ed.), Stuttgart 1866, p. 56f; Bayerische Staatsbibliothek. ↩︎