“On 31 May, we left the inn early in the morning. We arrived in a hamlet called Schettenbach at lunchtime. The hamlet was at the edge of the Bohemian Forest. In the afternoon, we crossed through the forest and arrived in Frauenburg after dusk. We were tired and soaked because it was raining all day.“1

From Regensburg to Prague

29 May – 3 June 1585

Samuel Kiechel had travelled on the Danube from Ulm to Regensburg. Now it was time for him to leave the river behind. The Danube was the last vestige of home for the young man. The river was the lifeline that tied towns and cities on its banks together. News and messages travelled on boats and barges together with goods and passengers. Regular contact along the river led to familiarity despite the distances.

As Samuel turned north and away from the river, he faced the practical issues of travelling in the sixteenth century for the first time: orientation, safety, companions, transport or the daunting task of walking long distances.

To Amberg

The road to Nuremberg

In the lower-left corner of the view of Regensburg, you see the road that leads to Nuremberg. In the background are the Danube and the gate of Stadtamhof, the town on the other side of the river from Regensburg. Samuel Kiechel left the city along this road towards his next destination, Amberg.

In a straight line, Amberg is about fifty kilometres north. But the road wound through the hills and across the upland of the Franconian Jura (Upper Palatinate Jura). For a traveller, the distance would have been considerably longer, too far for a person on foot to cross in one day. Kiechel had probably found a carriage to take him to his destination.

Kiechel arrived in Amberg after nightfall. Oddly, he did not mention difficulties when entering the town after sunset. In the sixteenth century, most places in central Europe were fortified by walls, and the gates were locked during the night. Our traveller would repeatedly take notice of this practice in his journal.

According to Kiechel, Amberg was the capital of the Upper Palatinate and under the rule of the Prince-Elector of Heidelberg (Electoral Palatinate).

Amber in Philipp Apian’s “Bairische Landtaflen“, 1568

The Holy Roman Empire was an elective monarchy. The privilege to elect a future King and Emperor was held solely by seven Prince-electors. Established in the thirteenth century, the Prince-electors were the three Archbishops of Cologne, Mainz and Trier, the Duke of Saxony, the Margrave of Brandenburg, the King of Bohemia and the Count Palatine. At the time of Kiechel’s visit, the Prince-Elector of Heidelberg was Frederick IV, Elector Palatine (1574-1610).

As with many other territories in the Holy Roman Empire, the Electoral Palatinate was not one contiguous domain. Despite the similarity in name, the Palatinate and the Upper Palatinate were different places. The Palatinate was a region along the upper Rhine, with Heidelberg as its capital. The Upper Palatinate was north of the Duchy of Bavaria and on the border with the Kingdom of Bohemia. Amberg was the capital of the Upper Palatinate. The Upper Palatinate was politically a part of the Electoral Palatinate despite the geographic distance and various smaller territories between them.

Samuel Kiechel stayed in Amberg for one night. The following day was Pentecost. Our traveller went to church in the morning and left the town in the afternoon.

Messengers and the Postal Service

One mile outside of Amberg, he met a messenger from Prague. The man was on the way home to the Bohemian capital. Both men agreed to travel together. Further along the road, Kiechel and the messenger met a monk from a monastery in Riedlingen. He joined the group as well.

In the late fifteenth and early sixteenth centuries, communication and the flow of information became increasingly important in politics and business. Major European powers had begun to develop some form of regular postal service. For example, the House of Habsburg established regular links between their domains. The first postal routes existed between the Habsburg courts in Germany, the Netherlands and Spain. Soon, however, this network expanded to other places. Initially, the postal service was supposed to transport only the letters of the respective rulers and their families. But people often ignored this restriction.

A German messenger, 1569

Soon, travellers began to use the postal system. They would accompany messengers on horseback or, where available, travel in postal carriages. In some travelogues, the use of postal services is called “postieren”, and it was the fastest form of travel at the time.

The new postal service organised and unified the transport of messages. So far, a single messenger often delivered letters from the sender to the recipient. Along the new postal routes, messengers on horseback were stationed at fixed intervals. The letters changed hands from one rider to the next (“posted” at “posts”). The line of messengers and the regular exchange of horses at each station significantly increased speed and reliability.

Messenger on horseback in front of an inn

The new measures proved popular but required structural changes, steady management and material support. Postal stations had to be established where messengers could wait and horses could be stabled. Roadside inns were considered the ideal facilities for this purpose because they provided accommodation, food and drink. The distances between postal stations were kept relatively uniform.

Roadside inns were also the places travellers would stop to exchange information about the road ahead, possible dangers and the distances. They were places to find transport, a guide and companions.

However, the new postal service was still in development, and the routes connected only major political and economic centres. Plenty of messengers on the road were still doing their job the old way. These messengers were a common sight and regular and welcome companions to travellers like Samuel Kiechel. Due to their knowledge of roads, directions, distances and the various towns along the way, they were the ideal guides.

Through the Bohemian Forest

Kiechel and his companions stopped at an inn called “Schindehitten” in the evening. Our traveller remarked that the name reflected the food and drink on offer.

The first part of the inn’s name, ‘schinden’, translates into ‘maltreated’. The service and available food in this place were presumably of poor quality. But the inn was in a remote area, and the travellers had no other options except to spend the night in the open.

The three men stayed in the inn and continued their journey the following morning. At lunchtime, they stopped in a settlement called Schettenbach at the edge of the Bohemian Forest.

The only place with a similar name is Schnaittenbach, northeast of Amberg. But the distance from Schnaittenbach to Přimda (the next destination) is about fifty kilometres. Even on horseback, this would have been too much to travel in an afternoon. Kiechel mentioned that the distance between the “Schindehitten” and Přimda was five miles (ca. 37 km). Schettenbach was, therefore, either another place closer to the Bohemian Forest that no longer exists or our traveller mistook the name.

In the afternoon, the three men crossed through the Bohemian Forest, a heavily forested mountain range that has been a natural border between Bavaria (Germany) and Bohemia (Czech Republic) for centuries. The area where Samuel Kiechel and his two companions passed through is called Upper Palatine Forest today.

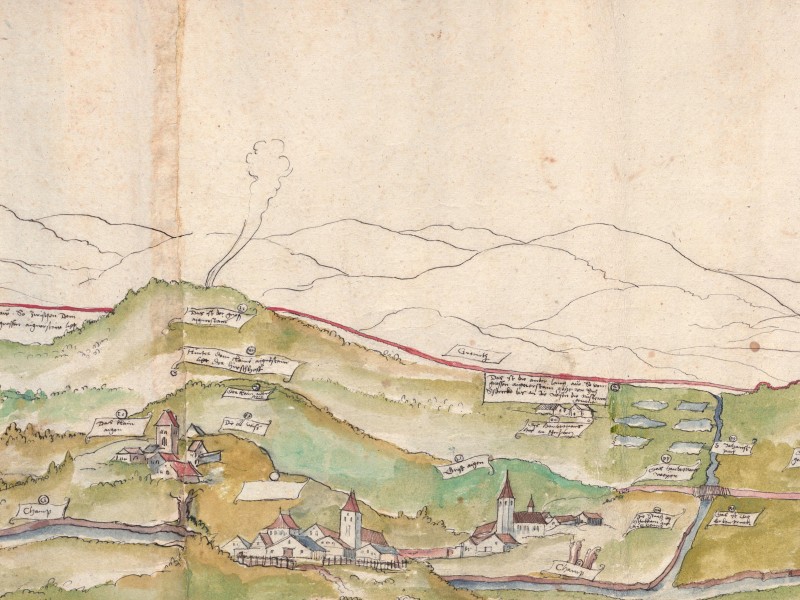

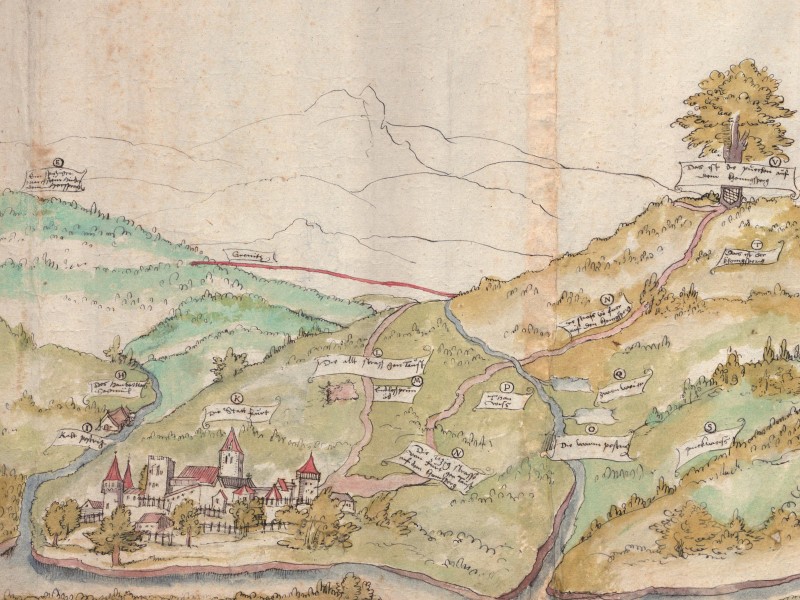

Philipp Apian, the mathematician who made the “Bairische Landtaflen” (Bavarian regional maps)2, had drawn some preliminary sketches of the area along the Bohemian Forest. The sketches are not in the top-down view of his map but from a low-oblique angle. The area depicted is a short distance from where Samuel Kiechel passed through. The drawings show forested hills and mountains and some towns and villages. Even a few roads can be seen leading into the Forest. But the area is sparsely settled.

The Bohemian Forest from the west, 1563

On the way to Bohemia, the travellers followed a road that was part of a network of routes collectively known as the “Goldene Straße” (Golden Road). The “Goldene Straße” was a trade route connecting Nuremberg with Prague. Its name signifies its economic importance. Merchants have used those roads to cross the Bohemian Forest since the Middle Ages, and they played a crucial role in trade and cultural exchange.

An interesting feature of Apian’s drawings is the red line in the background. It indicates the border between Bavaria and Bohemia. As a mapmaker, Apian was keen to draw the borders accurately. But the line is just a rough indication. In a densely forested area, borders were notoriously difficult to establish, mark and communicate. A traveller in the sixteenth century would rarely have to deal with border posts, fences, guards or checkpoints. However, the lack of a clear demarcation could lead to confusion and potential disputes.

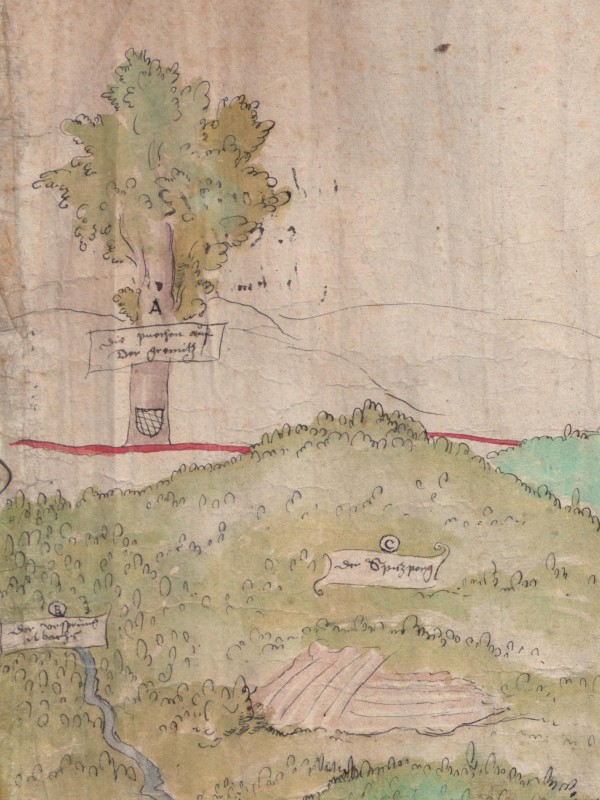

Drawing of a tree marking the border between Bavaria and Bohemia

What a border sign at the time might have looked like can be seen in the drawing. Along the red line, Apian drew individual, large trees with a shield or coat of arms below them. Trees, often oaks, were used to mark borders. Sometimes, markings were cut into the tree; at other times, a sign with a coat of arms was nailed onto it. The apparent drawback of those border marks was that trees could be cut down. In times of war, this was not uncommon.

Samuel Kiechel and his two companions arrived after nightfall in Frauenburg (Přimda), an unfortified market town on the Bohemian side of the Forest. The journey had been unpleasant. It had rained throughout the day. The three men were tired, and their clothes were soaked.

The group spent the night in the town and prepared to leave the following morning. But the monk from Riedlingen complained that he did not want to get into his wet clothes. In addition, he did not have enough money to pay for the accommodation. The monk had to stay behind, and Kiechel left Přimda with the messenger. Both men walked six miles to the city of Pilsen.

Towards Prague

The trade road from Nuremberg to Prague led through Pilsen. Presumably, Kiechel followed it down from the mountains. Pilsen is at the confluence of the rivers Mže and Radbuza. The cathedral of St Bartholomew, the town hall and various church and gate towers would have greeted our traveller from afar.

In Pilsen, Samuel Kiechel left his companion. Our traveller had met a citizen who planned to travel to Prague with his ‘housewives’. The term ‘housewives’ could mean the man’s wife and any daughters he had. It could also include female servants as, in early modern society, they would be considered part of the extended household.

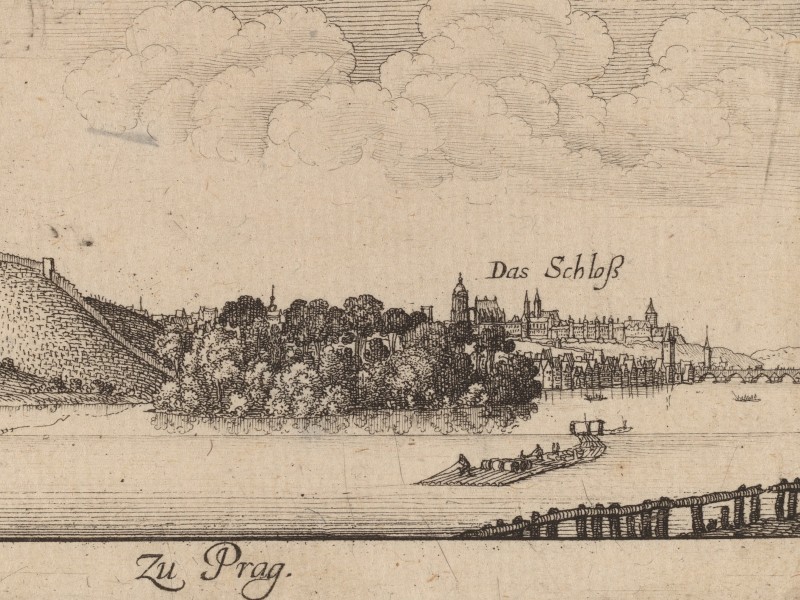

The man and his family travelled in their carriage and invited Kiechel to join them. They left Pilsen the next day and drove to Beraun (Beroun). They spent the night in the town and continued the following morning to Prague.

Illustrations & References

All images are in order of appearance with links to sources on external websites:

- Apian, Philipp: Sketches for the “Great Map of Bavaria”, 1563, Library of Congress.

- Regensburg, in: Braun, Georg, Hogenberg, Frans: Civitates Orbis Terrarum (5), Cologne 1599, fol. 51v; Heidelberg University.

- Apian, Philipp, Chorographia Bavariae, Ingolstadt 1568, map 2; Bayerische Staatsbibliothek.

- Bertelli, Ferando, Cursor Germanus, 1569; Rijksmuseum Amsterdam.

- de Hooghe, Romeyn, Koerier stapt van zijn paard voor een herberg, 1668; Rijksmuseum Amsterdam.

- Anonymous, Landschap met een herberg, c. 1500 – c. 1600; Rijksmuseum Amsterdam.

- van Uden, Lucas, Boslandschap, 1605 – 1673; Rijksmuseum Amsterdam.

- Apian, Philipp: Sketches for the “Great Map of Bavaria”, 1563, Library of Congress.

- Hollar, Wenceslaus: Zu Prag, 1635; National Gallery of Art, Washington, DC.

- Die Reisen des Samuel Kiechel aus drei Handschriften, K. D. Haszler (ed.), Stuttgart 1866, pp. 2-3; Bayerische Staatsbibliothek. ↩︎

- Philipp Apian, Chorographia Bavariae — Bairische Landtaflen. XXIIII. Ingolstadt 1568; Bayerische Staatsbibliothek. ↩︎