“London is the main and capital city of England, a royal, beautiful, large, sprawling and wide city, but nothing is fortified, and it has no walls; people can enter and leave the city by day and night.”1

In London

12 September – 13 November 1585

Samuel Kiechel had arrived late at night in London, having travelled by boat up the Thames from Gravesend. With little knowledge of the city and where to find accommodation, he stumbled across a bakery where the owner was still at work. The baker spoke French and permitted our traveller to spend the rest of the night there. The following morning, Kiechel departed with directions to the White Bear Inn. He knew that the inn belonged to a Dutchman and that German travellers frequently stayed there.

Maps, Views and Descriptions of Elizabethan London

The two oldest depictions of London are a panoramic view by the Flemish artist Anton van den Wijngaerde from around 1544 and the Woodcut Map of London (also known as the Agas Map of London) from approximately 1560.

The view by van den Wijngaerde comprises fourteen sheets and has been drawn to perspective. Westminster Palace and Abbey are visible on the left side of the view, while St. Paul’s Cathedral and London Bridge stand out in the middle, with the Tower discernible to the right. As usual, van den Wijngaerde’s drawing offers a lifelike impression of the city, indicating what travellers like Kiechel saw and experienced. The image is on the website of the Ashmolean Museum in Oxford.

The Woodcut Map has survived in fragments and later copies from the seventeenth century. Based on this and other resources, a project by the University of Victoria has recreated Elizabethan London as an interactive map (“Map of Early Modern London (MoEML)”).

The Woodcut Map displays many similarities to the view of London printed in the “Civitates Orbis Terrarum” and was likely used as a template for it. However, the scale of the Woodcut Map is considerably larger, providing much more detail.

London, 1572

In the “Civitates”, the bird’s-eye view of London is found in the first volume. The view depicts a large city situated mainly on the northern bank of the Thames River. Numerous boats are on the river, and a few larger ships appear on the right-hand side of the map, approaching the mouth of the Thames. Various places and buildings of interest are named on the map.

The final map I wish to present here was created by the cartographer John Norden in 1593. The map is closest in date to Kiechel’s visit. While other depictions show London and Westminster together, Norden produced a separate map for each location. The map of London includes an extensive legend with many street names and buildings.

In 1598, the historian John Stow published a detailed survey of Elizabethan London, with a second edition released in 1603. London is divided into twenty-six wards, and Stow guides the reader through them, akin to a walking tour. While Stow’s primary interest was the history of the places and buildings and the origins of their names, the survey is nonetheless an exceptional source for conveying an impression of England’s capital in the late sixteenth century.

First Impressions

London and the Thames from the west

According to Stow’s survey, a long thoroughfare divides London from east to west. It begins at Aldgate in the east and follows Aldgate Street, Leadenhall Street, Cornhill Street, Poultry and Cheapside Street to St Paul’s Gate and Ludgate in the west. There is no such apparent north-south divide. However, Stow notes that the narrow river Walbrook once partitioned London into an eastern and western part. By the late sixteenth century, this brook had been built over.2

The central role of the River Thames in London’s everyday life is evident in all the images. Numerous ships and boats can be seen travelling back and forth on the river. The Thames served as the city’s major thoroughfare, with around two thousand small boats (wherries) transporting passengers up, down or across the river. River transport was a faster and more comfortable way to navigate London than the crowded and narrow streets. Additionally, larger boats and barges of various sizes carried groups of passengers or cargo along the river.3

London Bridge, 1616

The only bridge across the Thames was London Bridge, which must have been a fascinating sight to behold. John Stow writes, “It is a work very rare, having with the draw-bridge twenty arches made of squared stone, of height sixty feet, and in breadth thirty feet, distant one from another twenty feet, compact and joined together with vaults and cellars; upon both sides be houses built, so that it seemeth rather a continual street than a bridge.”4

Between London Bridge and the Tower was the city’s port, with around twenty quays. Merchant ships, along with boats and barges, sailed up the Thames to moor there for loading or unloading. The vessels brought “fish, both fresh and salt, shell-fishes, salt, oranges, onions, and other fruits and roots, wheat, rye, and grain of divers sorts.” Here, Samuel Kiechel most likely arrived with the boat from Gravesend.5

Kiechel’s first impression of London was that of a royal, beautiful and large city. He commented that it was unfortified, allowing everyone to enter day or night. This must have been a new experience for a traveller from the continent, where towns and cities had fortifications and curfews. Kiechel noticed a castle (Tower) built near the River Thames. He also mentioned that much linen and cloth were traded in the city. Textiles were produced from the wool of the many sheep in England. Merchants in London also traded in unprocessed cloth.

Samuel Kiechel noted that London was unfortified. However, some fortifications, in the form of walls and a moat, are visible in all maps and views of London. Kiechel may not have noticed them because the walls no longer marked the city’s borders. London had expanded massively. From a population of around 70.000 people when Elizabeth I ascended to the throne in 1558, the population would grow to around 200.000 at the time of her death in 1603. London was by far the largest city in England. Due to the increase in population, people began to build houses outside the walls, and soon, the old fortifications were overwhelmed by the city, which spread into the surrounding countryside. John Stow laments in his survey of London that the ditch (moat) and walls had disappeared beneath gardens and houses.6

Walking through the Heart of London

Billingsgate, 1598

The port of London was situated in the Billingsgate and Tower Street Wards. The “Survey of London” states that along Thames Street, the longest street in the city, there are numerous large merchants’ warehouses and the Customs House. Kiechel’s boat from Gravesend likely landed in this area. The pastry baker who provided shelter to the traveller for the remainder of the night was most likely located on Thames Street by the river. Stow mentions that cooks and pastry bakers have their shops along this street.7

After spending the night in a bakery, Kiechel left for the White Bear Inn. The inn was located on Basinghall Street in the Basinghall Ward (now Bassishaw Ward), one of the smallest wards in London. To get there, our traveller had to cross the city’s centre. As a stranger following directions provided to him, it is reasonable to assume that he kept to the larger streets.

The Port in Billingsgate Ward and New Fish Street on the Agas Map

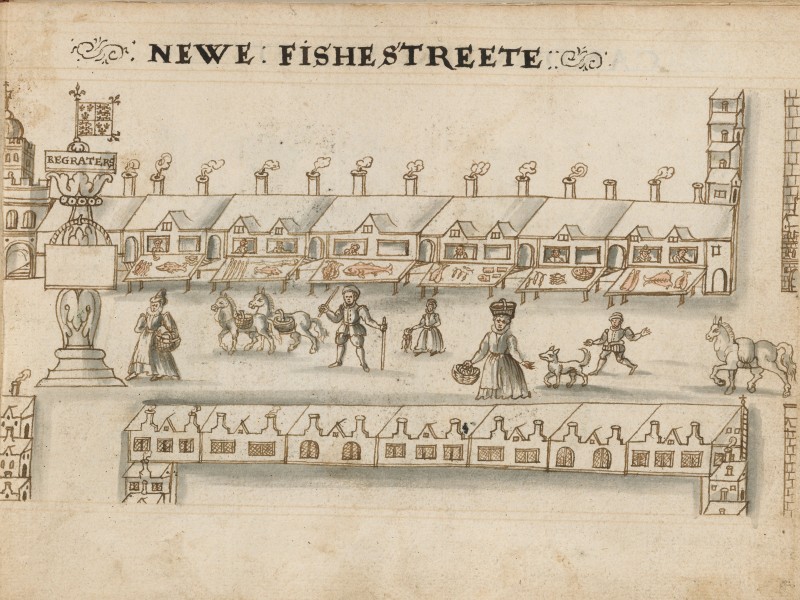

He may have walked along New Fish Street. The street originated at London Bridge, close to the port, and extended northward. Being directly connected to the bridge, it served as a significant access to the heart of London. According to Stow, fishmongers’ houses and various taverns lined the street. New Fish Street crossed Eastcheap Street, where the meat market was situated, and where many butchers lived.8

New Fish Street, 1598

After crossing Eastcheap, New Fish Street became Gracechurch Street. Kiechel might have continued along it until he reached the crossroads with Lombard Street. On Lombard Street, the traveller would have turned left.

Gracechurch Street and Lombard Street

Lombard Street was named after the Italian merchants and bankers who were permitted to settle there in the late Middle Ages. The street remained a hub of commercial activity in the sixteenth century and was close to the Royal Exchange on Cornhill Street.

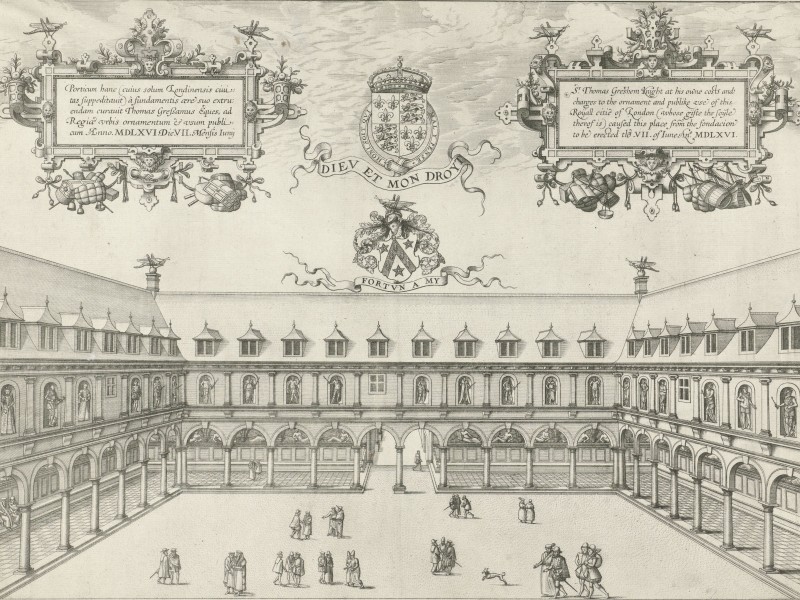

Royal Exchange, 1569

Samuel Kiechel would visit the Royal Exchange during his two months in London. After his visit, he wrote: The merchants of London meet daily in a beautiful building called ‘Börse’ (Royal Exchange). It is a square building with a broad and open yard in the middle. Arcades on all four sides surround the yard, allowing people to walk there during rain and stay dry. At the Royal Exchange, all sorts of goods are sold. Whatever someone needs, it is available there. The merchants of the Royal Exchange have a custom: they return home for lunch at one o’clock every day, despite some having to walk for half an hour. The same custom can also be observed in Antwerp and other places in the Netherlands. Before the merchants leave their homes in the morning, they have breakfast.

The Royal Exchange was founded in 1565 by Thomas Gresham. The building was modelled on the Antwerp Exchange.

The crossroad of Cornhill, Poultry and Lombard Street with the Royal Exchange on the right and the Stocks Market on the left

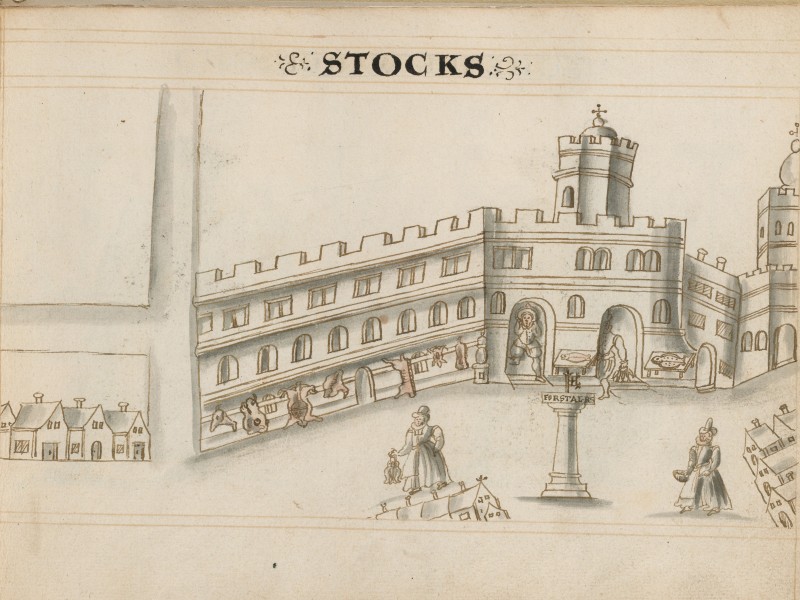

Following his route to the inn, Samuel Kiechel would have walked along Lombard Street until he reached a major crossroad in London. The east-west thoroughfare, with Cornhill Street to the east and Poultry to the west, met Threadneedle Street from the north and Lombard Street from the south. To his left, Kiechel would see St. Mary Woolchurch, and as he walked past it into Poultry, he would pass the Stocks Market where meat and produce were sold.

The Stocks, 1598

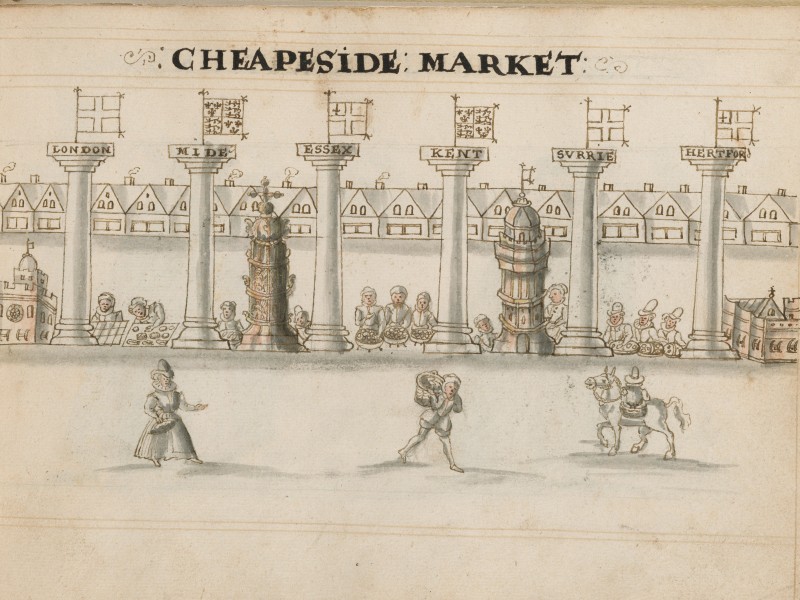

Soon, Poultry would open up onto Cheapside Street. According to John Stow, Cheapside derived its name from a market called West Cheping. It was the central marketplace and the widest street in London, as well as the wealthiest street, lined with the shops and houses of merchants and goldsmiths on both sides. Most of those houses were three or four stories high.9

Cheapside, 1598

At the eastern end of Cheapside, where Kiechel entered, stood the Great Conduit and Mercers’ Hall. The Great Conduit was a fountain connected to underground channels and pipes that supplied the city with drinking water. It was constructed in the mid-thirteenth century, and the channels were later extended into other parts of the city. Another fountain, the Standard, stood further west on Cheapside.10

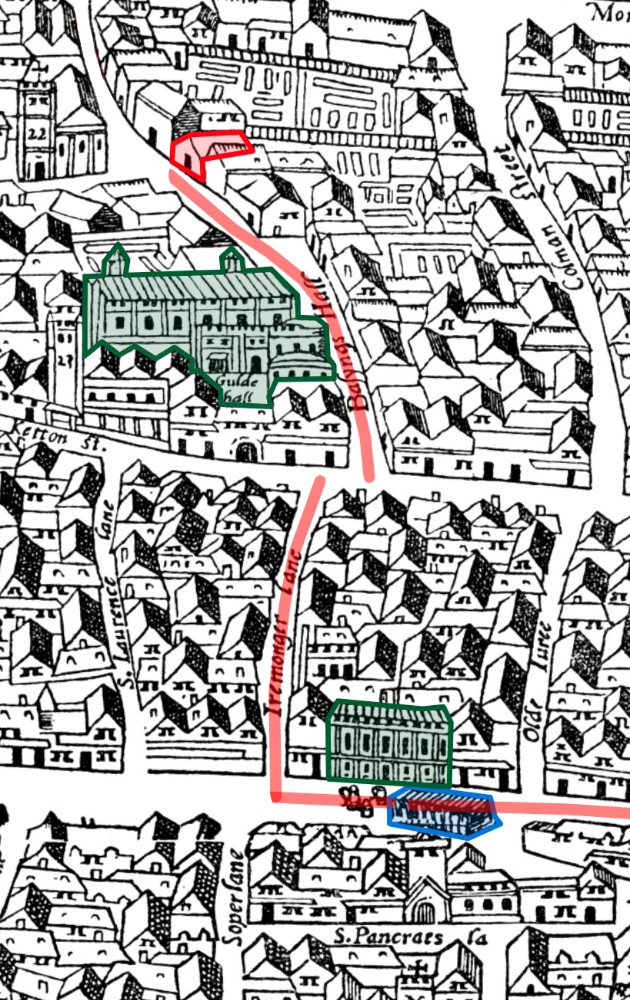

Cheapside with the Mercer’s Hall and the Conduit at the bottom, the Guildhall in the centre and White Bear Inn at the top

The Mercers’ Hall stood just north of the Great Conduit, and Samuel Kiechel would have passed it on his right-hand side. Mercers were merchants, and the Worshipful Company of Mercers was one of the livery companies of London. Livery companies were trade associations or guilds established to regulate their professions. The companies were very protective of their trade, allowing only their members to work in their craft. This protectionism ensured the quality of their products and the training of their craftsmen. The Mercers were the oldest and first in rank among the livery companies. The coats of arms of the twelve highest-ranking companies are displayed on the left and right edges of John Norden’s map of London.

Past the Mercers’ Hall, Samuel Kiechel would have turned right into Ironmonger Lane, where metalworkers lived.11 Walking down this lane, he soon found himself in front of the Guildhall, London’s town hall and the administrative heart of the city. On the right side of the Guildhall was Basinghall Street, lined with merchants’ houses. Between the Halls of the Girdlers and the Weavers, two of the livery companies of London, and opposite the church of St Michael Bassishaw, was the White Bear Inn.

Much like in our time, foreign travellers often gravitated towards specific, well-known inns and hostelries owned by countrymen. Language barriers did not exist in those establishments; information and advice about the city could be shared, and occasionally, guided tours to notable attractions were organised. These inns allowed travellers to find companions to spend time with or travel alongside. Like modern tourists, early modern travellers sought the company of fellow countrymen. For visitors from Germany, the White Bear Inn in London was one such place.

Close to the Guildhall and Cheapside, the inn was situated in an affluent area of the city. According to Kiechel, its guests were mainly German travellers from noble families or, like our traveller, prosperous merchant families. In the inn, Kiechel found companions to occupy his time in London and explore the city’s attractions.

Illustrations & References

All images are in order of appearance with links to sources on external websites:

- Smith, William, London, 1588; British Library.

- London, in: Braun, Georg, Hogenberg, Frans, Civitates Orbis Terrarum (1), Cologne 1593, fol. A; Heidelberg University.

- Hollar, Wenceslaus, Londen gezien over de Theems vanuit Milford Stairs, 1643 – 1644; Rijksmuseum Amsterdam.

- Visscher, Claes, Londinum florentissima Britanniae urbs, 1616; Folger Shakespeare Library, Washington DC.

- Billingsgate, in: Alley, Hugh, A caveatt for the citty of London, or, A forewarninge of offences against penall lawes [manuscript], 1598, fol. 9r; Folger Shakespeare Library, Washington DC.

- The Route of Samuel Kiechel reconstructed on: Jenstad, Janelle, Newton, Greg, McLean-Fiander, Kim (eds.), The Agas Map of Early Modern London, 2013-present; University of Victoria, Victoria, BC.

- New Fish Street, in: Alley, Hugh, A caveatt for the citty of London, or, A forewarninge of offences against penall lawes [manuscript], 1598, fol. 10r; Folger Shakespeare Library, Washington DC.

- Hogenberg, Frans, Beurs in Londen, 1569; Rijksmuseum Amsterdam.

- Stocks, in: Alley, Hugh, A caveatt for the citty of London, or, A forewarninge of offences against penall lawes [manuscript], 1598, fol. 14r; Folger Shakespeare Library, Washington DC.

- Cheapside, in: Alley, Hugh, A caveatt for the citty of London, or, A forewarninge of offences against penall lawes [manuscript], 1598, fol. 15r; Folger Shakespeare Library, Washington DC.

- Die Reisen des Samuel Kiechel aus drei Handschriften, K. D. Haszler (ed.), Stuttgart 1866, p. 22; Bayerische Staatsbibliothek. ↩︎

- Stow, John, Survey of London, 1598, pp. 107f. ↩︎

- Ibid., p. 13. ↩︎

- Ibid.; pp. 25f. ↩︎

- Ibid.; p. 185. ↩︎

- Ibid., pp. 19f. ↩︎

- Ibid., p. 124. One bakery in Billingsgate Ward, which would gain unfortunate fame in 1666, was the Bakery of Thomas Farriner, where the Great Fire of London supposedly began. The bakery was situated on Pudding Lane (offal was referred to as pudding, and butchers used the lane to transport said offal to the river for disposal by boats; Stow, John, Survey of London, 1598, p. 189). ↩︎

- Ibid., pp. 190-194. ↩︎

- Ibid., pp. 240f, Mortimer, Ian, The Time Traveller’s Guide to Elizabethan England, London2021, p. 34. ↩︎

- Stow, Survey, p. 237. ↩︎

- Ibid., p. 242. ↩︎