“Every day, comedies are performed, and it is entertaining to watch the Queen’s Men play, but for a foreigner who does not speak the language, it is dispiriting not to understand it.”1

In London

12 September – 13 November 1585

After arriving in London in the middle of the night, Samuel Kiechel found accommodation at the White Bear Inn in the heart of the city. There, he met other travellers, many of whom were noblemen, and together they visited Westminster Abbey, the Tower, and the theatre.

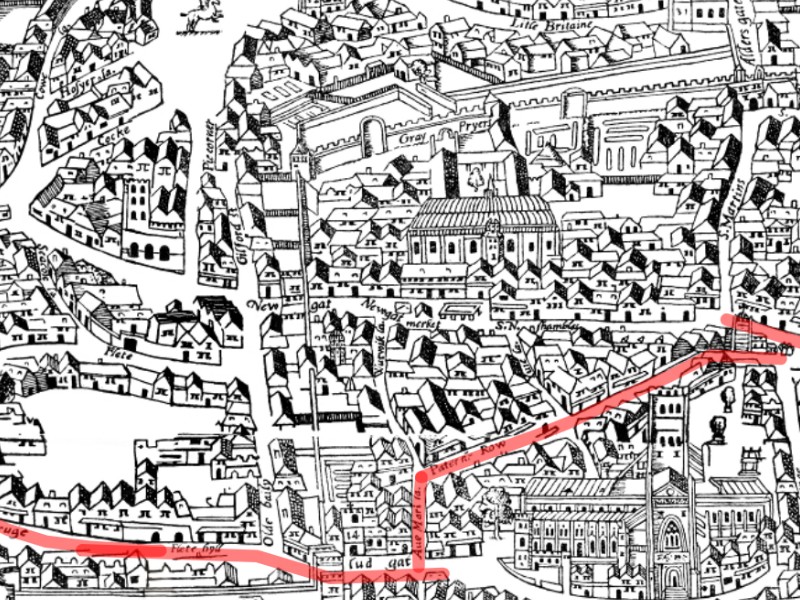

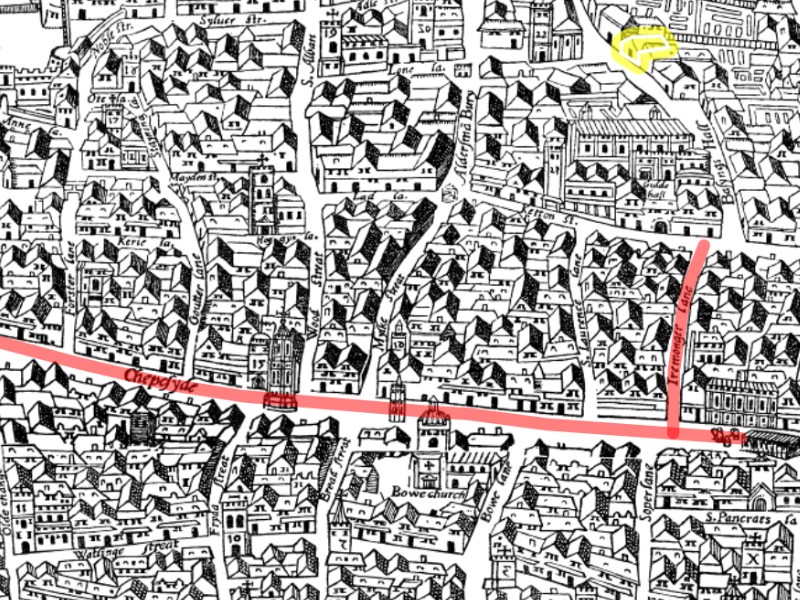

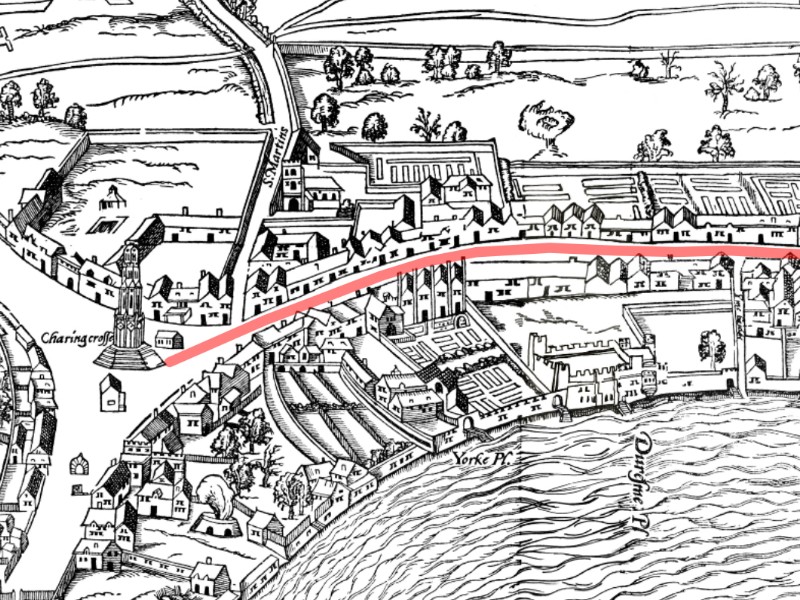

The Route to Westminster

The route from the White Bear Inn (top right) via Cheapside, Paternoster Row and Ludgate on the Agas Map

From the inn on Basinghall Street, the easiest route to Westminster was to walk south to Cheapside, London’s main thoroughfare, then head west to where it split into Newgate Street and Paternoster Row just north of St Paul’s Cathedral. The group would have turned onto Paternoster Row and continued to Ludgate Street, passing through the old boundary of London via Ludgate, a gate built in Roman times. From the gate, the route to Westminster was simple, following Fleet Street and The Strand to Charing Cross.

Samuel Kiechel mentioned that he saw the palaces of many great lords in London, including the palace where the Queen would stay during her visits to the city. He remarked that these places were located near Westminster Abbey. According to John Stow’s “Survey of London”, many grand houses belonging to bishops and the nobility lined Fleet Street and The Strand.

The Strand and Charing Cross

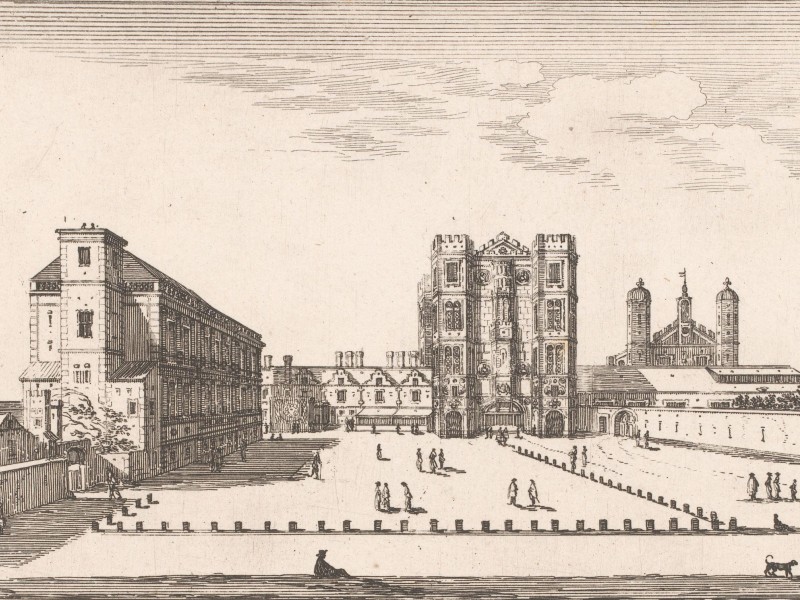

Kiechel mentioned that the Queen’s palace was situated close to the river, describing it as an old building of mediocre quality. He noted that when the Queen visited the city, the rooms and halls of the palace were adorned with beautiful tapestries. However, when she departed for another location, everything was taken down, leaving only the bare walls behind.2

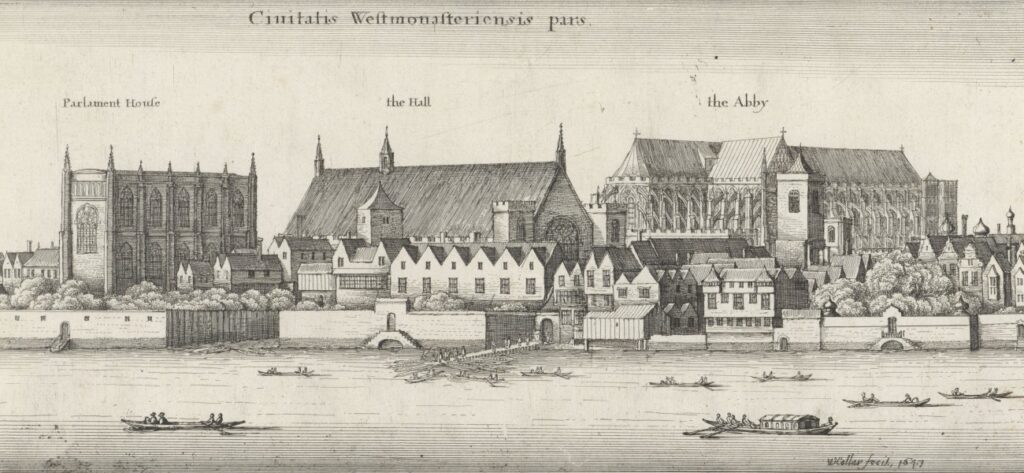

The Palace of Whitehall, mid-17th century

The palace stood south of Charing Cross (Whitehall) but was destroyed by fire in 1698. John Stow asserts that its origins date back to Edward the Confessor. Henry VIII reconstructed the palace, and in the late sixteenth century, it served as the Queen’s main residence when she visited the city.

Kiechel also saw many beautiful gardens in London. However, their beauty depended on the quality of the soil. Kiechel judged that the gardens were not comparable to those in Italy since no wine was cultivated on the island. These gardens were most likely also located in the area of Westminster and The Strand, as only wealthy individuals could afford the space and expense of planting a garden.

Westminster Abbey

Our traveller describes Westminster Abbey as a large, beautiful building. A guide accompanied him and his companions into the Abbey. Kiechel wrote that all English kings and queens were crowned there and, after their deaths, buried in the church. He saw their tombs in the choir. Some tombs were made of white marble, while others were of alabaster, each decorated with an image of the king or queen carved into it.

Kiechel noticed a simple, inexpensive-looking wooden coffin to the left of the choir. The guide told our traveller that it belonged to a former Queen of England. She had been placed in the coffin, and even after 200 years, her body has not decomposed. The coffin’s lid was open, and when the visitors touched the body, the flesh felt hard and dry like wood.3 Kiechel noted that the body looked almost like one of the Egyptian mummies.

The mummified body in the coffin in Westminster Abbey was Catherine de Valois (1401-1437), wife of King Henry V. Her mummified remains had been a popular attraction at the time. John Stow writes: “Katherine, his [Henry V] wife, was buried in the old Lady chapel 1438, but her corpse being taken up in the reign of Henry VII., when a new foundation was to be laid, she was never since buried, but remaineth above ground in a coffin of boards behind the east end of the presbytery.”4

Samuel Kiechel also noted that he saw a chair in the chapel of Westminster Abbey that looked like it was made of stone, featuring a relatively simple design. This chair was used for the crowning of English kings. Kiechel further saw the clothing and attire of former monarchs, noting that their garments were of poorer quality compared to those of his own era.

The chair Kiechel referred to was the Coronation Chair, and although it wasn’t actually made of stone, it contained the Stone of Scone. This stone was previously used in the coronations of Scottish kings. Edward I took it during his invasion of Scotland in 1296, and he commissioned the Coronation Chair in the same year. It has been used in all subsequent coronations.

Once Kiechel and his companions completed their tour of the Abbey, they departed after paying the man who had guided them and unlocked the chapel for them.

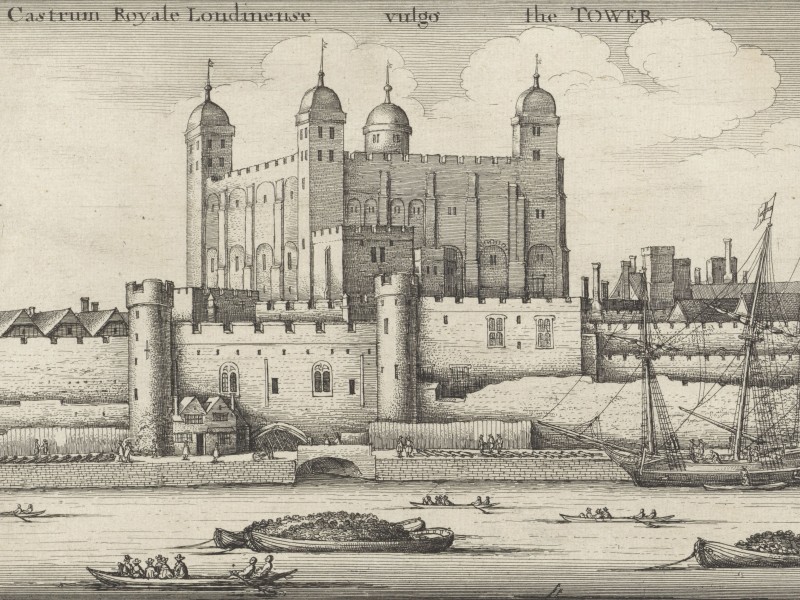

The Tower

On 19 September, Kiechel and the travellers he had met in London visited the Tower. The Tower was situated on the Thames at the eastern end of the city. To reach it, Kiechel might have retraced his route from the port in Billingsgate. The adjacent ward was Tower Street ward, and as the name suggests, its main street led directly to the Tower.

The Tower, 1647

Kiechel wrote: The Tower was heavily guarded, and visitors could not enter with their weapons. All weapons had to be left in the guardhouse for safekeeping.

In the Tower, a guide led the visitors into a room, displaying numerous pieces of jewellery made of gold and gems. Next, he guided the group into another room filled with exquisite curtains, tapestries, and pillows. Kiechel noted that these items were crafted from silk and gold, with many adorned with pearls. Our traveller remarked that most of these items were stacked to about head height on top of each other. He observed that many rooms and halls could have been furnished with them, lamenting that they were not used.5

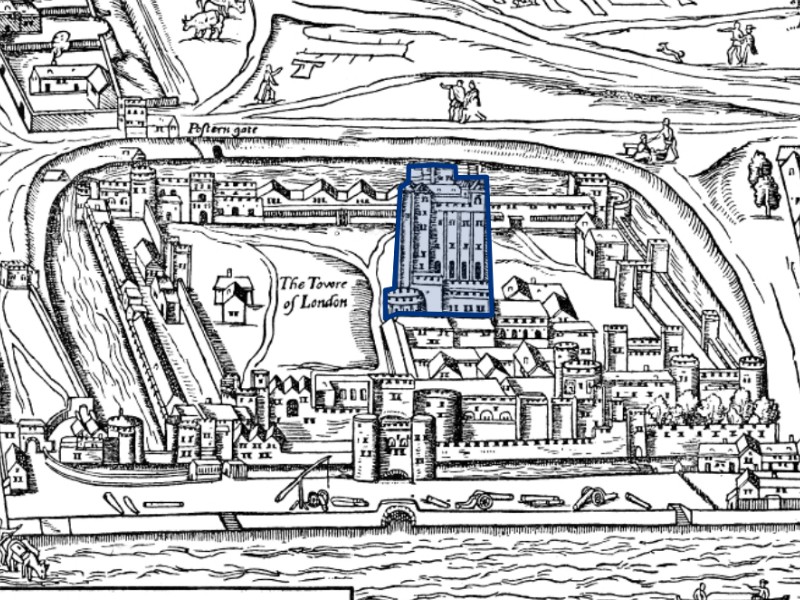

Both rooms Kiechel had visited so far were in the central part of the castle, known as the White Tower. In the same building were also two armouries. Our traveller observed numerous cannons stored there, along with armour, pikes, arquebuses and other weapons. Most of the weaponry appeared rather old-fashioned. Additionally, many bows and arrows were kept in storage.

The Tower and White Tower on the Agas Map

Next, the visitors were shown an eagle, a lynx and eight lions. These animals were also housed in the same building (White Tower) and belonged to the Queen.

By the late sixteenth century, the Tower was no longer a royal residence. Instead, it served various functions and was an attraction for visitors. According to John Stow’s “Survey of London”, the Tower was “a citadel to defend or command the city; a royal palace for assemblies or treaties; a prison of state for the most dangerous offenders; the only place of coinage for all England at this time; the armoury for warlike provision; the treasury of the ornaments and jewels of the crown; and general conserver of the most records of the king’s courts of justice at Westminster.”6 It also housed the royal menagerie with its exotic animals. For a fee, guides or wardens showed visitors around.7

The Tower is recognisable on all the maps of London mentioned earlier. It formed a distinct set of fortifications on the city’s eastern edge next to the Thames. Walls, a moat and several gatehouses separated it from the city. The characteristic appearance of the oldest part of the fortification complex, the Norman White Tower, is most clearly visible in Anton van den Wyngaerde’s panoramic view of London. The Flemish artist even made a separate drawing of the Tower. It may have been a preliminary sketch for his panorama.

Animal Baiting

While writing about his visit to the menagerie at the Tower, Kiechel mentioned that he saw more animals in a house on the other side of the river near the bridge. There, sixteen bears, two times 250 and sometimes more English bulldogs, a small horse and two bulls were kept. The owner of the building made a significant profit because, on Sundays and Thursdays, when a hunt took place, many people came to watch it. The word ‘hunt’ in this context refers to animal fights.

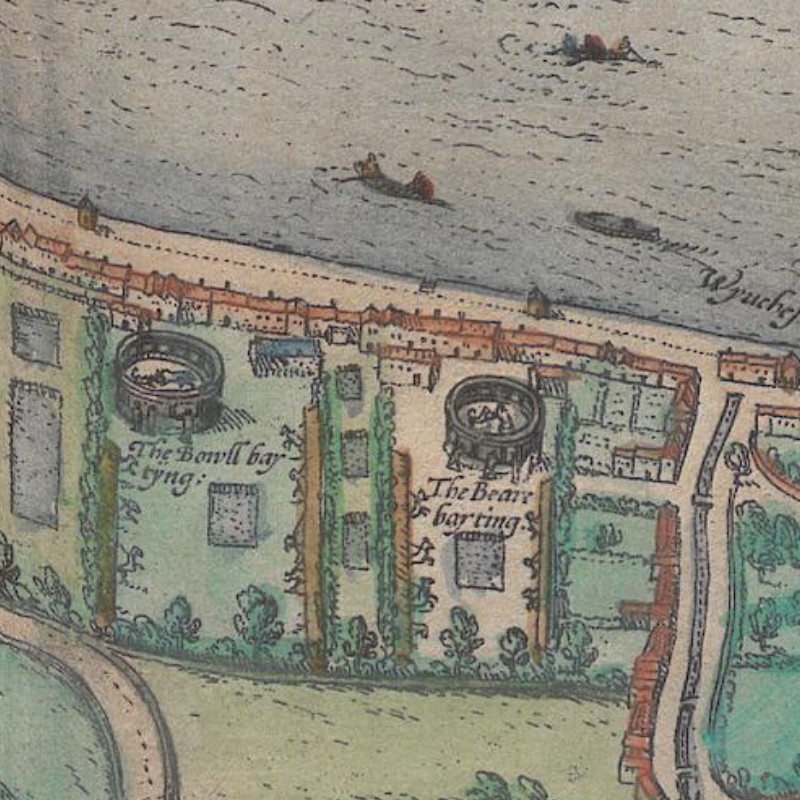

The two houses for animal fights on the southern bank of the Thames.

On Norden’s map of London, a place called ‘Beargarden’ is situated south of the river. Both the Woodcut Map and the view in the “Civitates Orbis Terrarum” depict two houses named “The Bearebayting” and “The bolle bayting.” In all three maps, these buildings are located in the sparsely built-up area south of the Thames in the district of Southwark. These houses are absent only from van den Wyngaerde’s panoramic view of London. However, as his view is the oldest of the images, the arenas might not yet have been constructed.

John Stow also wrote about these places in his “Survey of London”: “ … there be two bear gardens, the old and new places, wherein be kept bears, bulls, and other beasts, to be baited; as also mastiffs in several kennels, nourished to bait them. These bears and other beasts are there baited in plots of ground, scaffolded about for the beholders to stand safe.”8 Visitors wishing to watch the animals fight had to pay an entrance fee of one penny.9

Regarding the animal fights, Kiechel wrote: Inside the house was a large open area with a wooden pillar in the middle. A bear was tied to the pillar. Next, two, three, four, or more dogs were released. The dogs were young and trained to attack. If the bear caught a dog, it would strike it with its front paw, and the dog would be unable to attack. In bullfights, if a bull caught a dog with its horns, it would toss it into the air. Often, pieces of the dog’s skin were torn off by such an attack. The small horse kept in the arena was not tethered but had to run from the dogs and kick at them.10

Various descriptions of animal fights on the south bank of the Thames during the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries have survived. The detailed account of the spectacle in Samuel Kiechel’s journal suggests that our traveller probably witnessed such a fight.

Another popular spectacle among Londoners was cockfighting. The fights took place in various locations across the city, attracting large crowds. The fascination with this blood sport lay not only in watching the fights but also in betting on the animals.11

Entertainment: Elizabethan Theatre

Samuel Kiechel found London not a dull place. He noted that a wealth of entertainment was available to visitors, including fencing, dancing, music and learning to play a string instrument. People could also learn various languages such as French, Italian, Spanish, Dutch and English. London had schools for each of these languages, as well as churches offering services in multiple tongues. Besides English churches, there were Dutch, Italian and French churches with their respective preachers.

Moreover, London boasted ballrooms, and comedies (plays) were performed daily. Kiechel attended one of these plays and mentioned that it was particularly entertaining to see the Queen’s “comedianten” act on stage. However, he remarked that a foreigner unfamiliar with the language might find it difficult to understand much of it.12

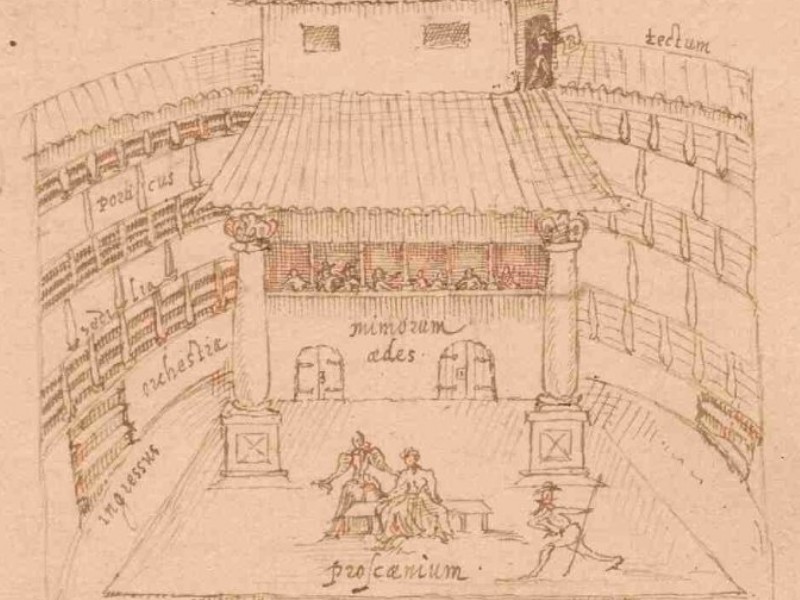

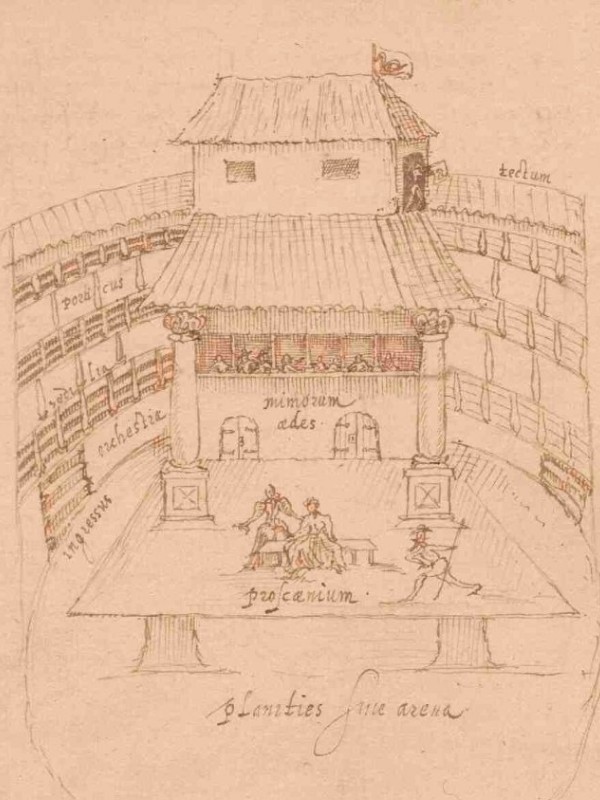

The Swan Theatre, ca. 1600

The word “comedianten” (Komödianten) is an old-fashioned German term for actors who mainly performed in comedies and should not be confused with the modern term comedian. The Queen’s Men was a popular theatre company founded in 1583, and Kiechel may have seen one of their performances. Alternatively, he might have found a particular character especially amusing. Theatre companies included clowns among their members, and one of the most renowned clowns of Elizabethan England was Richard Tarlton, who performed with the Queen’s Men.13For someone who did not speak English, watching a clown prance about could have been the most captivating part of the show.

Samuel Kiechel observed that plays were performed in dedicated venues (theatres) across London, where large audiences gathered to watch. These venues were constructed with three storeys stacked vertically. Theatre owners could earn fifty to sixty Thalers from a single performance, especially if it featured a new play that justified doubling the entry fee. Plays were staged throughout the week, excluding Fridays and Saturdays, although this rule was often disregarded.

Until the mid-sixteenth century, theatrical productions mainly consisted of miracle plays and scenes from the Bible. However, these plays were seen as remnants of Catholic tradition under Elizabeth’s reign and faced suppression. Nonetheless, it was not force or suppression that drove the developments that defined theatre for centuries; rather, public interest shifted towards secular plays. The first English play incorporating blank verse was performed for Queen Elizabeth in 1562. It was a success, and subsequent plays followed suit.14

Shortly thereafter, theatre companies began performing in the yards of large inns, such as the Boar’s Head in Whitechapel Street. The actors were all male, with boys dressed as women to portray female roles.

Following the success and popularity of these performances, the first purpose-built theatre, the Red Lion in Whitechapel, was constructed in 1567. However, it failed to attract large audiences because it was situated too far from the city, leading people to continue watching performances in the inns instead.15

The first commercially successful theatre, The Theatre, was constructed in the Shoreditch district north of the city in 1576. A year later, The Curtain, another theatre, opened nearby.

The Theatre was a polygonal building with an open yard in the centre and three galleries. Kiechel describes a structure with three corridors stacked one above the other, and he may have visited The Theatre to watch a play.

In 1587, The Rose opened in Southwark, followed by The Swan in 1595 and The Blackfriars Theatre in 1596. In 1598, The Theatre was closed and dismantled, with its materials reused to build The Globe. The theatres changed their programmes daily, presenting new plays regularly.16

The Globe, 1647

Attending plays was extremely popular among all social classes in Elizabethan London. People would queue for entry. The admission fee was one penny for standing in the yard in front of the stage, with extra charges for those wishing to secure a place in the gallery. Unlike modern performances, the audience was far from silent. They would chat, and vendors moved through the crowds selling snacks and drinks. There was also a risk of pickpockets.17

Elizabethan theatre must have been a truly novel experience for Samuel Kiechel. 1585 was still before the time of Shakespeare and other renowned English playwrights of the Elizabethan Age. Nonetheless, theatre performances were already developing, laying the foundation for the revolution that would occur in a few years.

Following these observations, Kiechel remarks that, in comparison to the countless activities available in London, life outside the city was distinctly different, and the locals were not very welcoming. This observation seemed quite common among travellers. Other visitors of his period also commented on an unfriendly, suspicious and sometimes hostile attitude towards them.18

Illustrations & References

All images are in order of appearance with links to sources on external websites:

- The Swan Theatre in London, in: Buchelius, Arnoldus, Adversaria, Hs. 842 (Hs 7 E 3), 1592-1621, fol. 132r; Utrecht University Repository.

- The Route of Samuel Kiechel reconstructed on: Jenstad, Janelle, Newton, Greg, McLean-Fiander, Kim (eds.), The Agas Map of Early Modern London, 2013-present; University of Victoria, Victoria, BC.

- Silvestre, Israël, Gezicht op het paleis van Whitehall in Londen, 1631-1661; Rijksmuseum Amsterdam.

- Hollar, Wenceslaus, Civitatis Westmonasteriensis pars, 1647; Rijksmuseum Amsterdam.

- Hollar, Wenceslaus, Castrum Royale Londinense vulgo the Tower, 1647; Rijksmuseum Amsterdam.

- Braun, Georg, Hogenberg, Frans, Civitates Orbis Terrarum (1), Cologne 1593, fol. A; Heidelberg University.

- Noseret, Luis Fernandez, Stier aangevallen door honden, 1795; Rijksmuseum Amsterdam.

- The Swan Theatre in London, in: Buchelius, Arnoldus, Adversaria, Hs. 842 (Hs 7 E 3), 1592-1621, fol. 132r; Utrecht University Repository.

- Hollar, Wenceslaus, London [the long view], 1647; British Museum.

- Die Reisen des Samuel Kiechel aus drei Handschriften, K. D. Haszler (ed.), Stuttgart 1866, p. 29; Bayerische Staatsbibliothek. ↩︎

- Kiechel, Reisen, pp. 30f; see: Mortimer, Ian, The Time Traveller’s Guide to Elizabethan England, London 2021, p. 28. ↩︎

- Kiechel, Reisen, p. 23. ↩︎

- Stow, John, Survey of London, 1598, pp. 408f. ↩︎

- Kiechel, Reisen, p. 24. ↩︎

- Stow, Survey, p. 55. ↩︎

- Mortimer, Time Traveller’s Guide, p. 321. ↩︎

- Stow, Suvey, p. 360. ↩︎

- Mortimer, Time Traveller’s Guide, p. 334. ↩︎

- Kiechel, Reisen, pp. 24f. ↩︎

- Mortimer, Time Traveller’s Guide, p. 333. ↩︎

- Kiechel, Reisen, pp. 28f. ↩︎

- Mortimer, Time Traveller’s Guide, p. 355. ↩︎

- Ibid., pp. 351f. ↩︎

- Ibid., pp. 352f. ↩︎

- Ibid., pp. 353f. ↩︎

- Ibid., pp. 356f. ↩︎

- Ibid., pp. 115-117. ↩︎