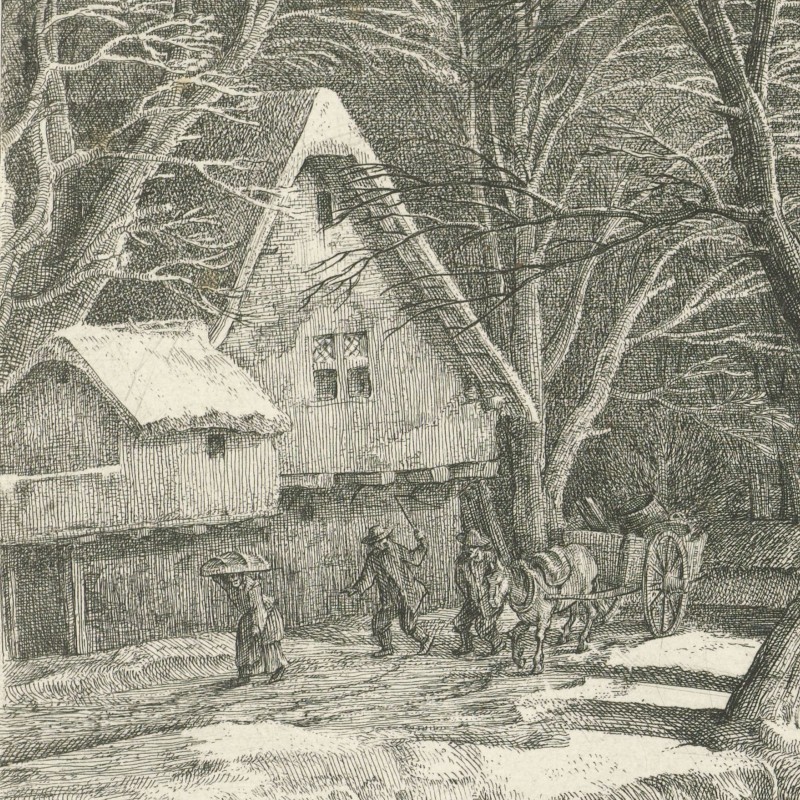

“Heavy snow began to fall and cover the tracks. The carters could not see where they were driving and went off the road. Often, their horses stood up to their bellies in deep snowdrifts and could barely move.”1

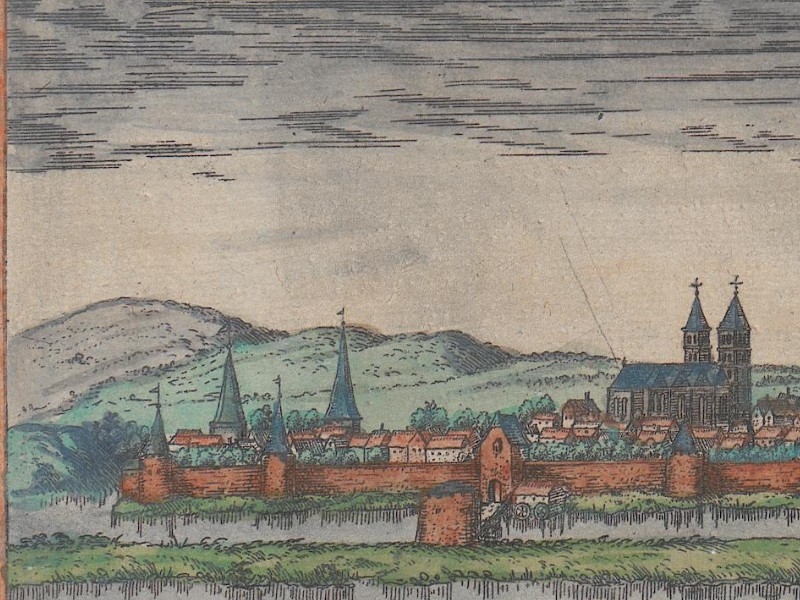

From Münster to Hamburg

01 January – 10 January 1586

After spending the end of 1585 in Münster, Samuel Kiechel found a farmhand who claimed to know the way to Osnabrück. The city was his next stop on his return journey to Hamburg. Although the land between Münster and Hamburg was no longer as threatened by banditry as the areas around Cologne and the Rhine River, it was January. Temperatures had dropped, and the roads were covered with deep snow, making the journey difficult and dangerous.

To Osnabrück

Samuel Kiechel left Münster with his new companions, the farmhand he had hired to carry his bag and lead him to Osnabrück. Unfortunately, soon after departing, our traveller realised that his supposed guide was unfamiliar with the route.

Getting lost was one thing, but the area around Münster was also unsafe. Kiechel had heard that a company of Spanish soldiers had been spotted two miles from the city. They were supposed to escort the Elector of Cologne to the Bishop of Münster. However, many soldiers at the time were mercenaries. The experiences of previous weeks had heightened Kiechel’s awareness of the dangers when travelling in this region. Sometimes, there was no clear distinction between bandits and mercenaries. And who would miss a lone traveller?

Suspicion arose about a mile outside Münster when Samuel Kiechel noticed that two men had begun to follow him. According to their clothing, they appeared to be a peasant and a soldier. They kept at a fixed distance and followed him for two hours. Kiechel urged his companion to hurry. Eventually, they reached a village where they decided to rest and wait, hoping their pursuers would move on.

Map of northern Westphalia with Münster at the bottom and Lengerich and Tecklenburg Castle at the top, 1595

After a long rest (and a jug of beer), Samuel and the farmhand decided to press on, as it was getting late. The two men who had been following them had disappeared. However, now our traveller was worried that they had gone ahead and were waiting for him along the road. Nonetheless, he continued and reached the village of Lengerich in the evening without incident. Kiechel saw Tecklenburg Castle to the left of the settlement, high in the mountains.

Our traveller stayed overnight in Lengerich and set out again the following day. During the night, snow fell and covered the road, making it hard to see the path. Soon after leaving the village, the two men lost their way and wandered through a forest for three hours before finding the road again. Due to these problems, Kiechel arrived in Osnabrück in the afternoon, despite it being only two miles from Lengerich.

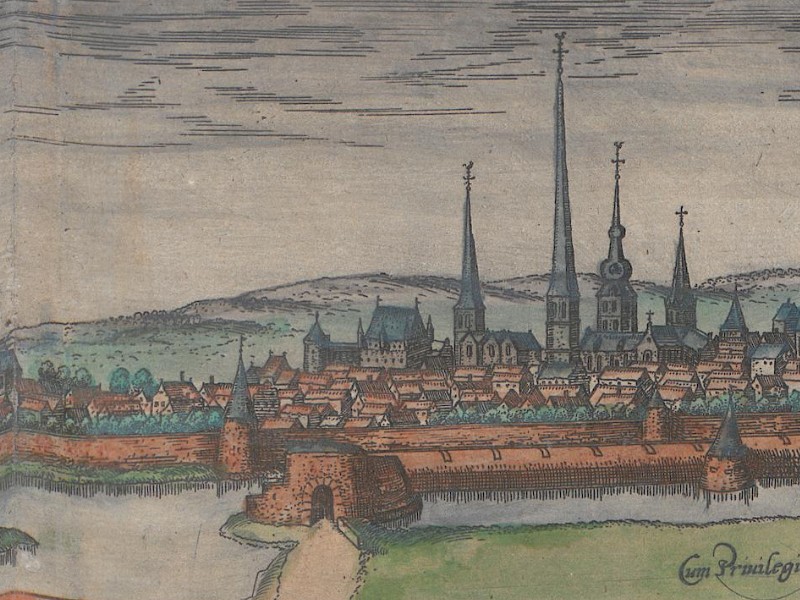

In Osnabrück

According to Samuel Kiechel, Osnabrück was large and old. It was poorly fortified and looked neglected and uninviting. The city was the seat of a bishopric, with a small river called Hase flowing outside its walls. However, our traveller praised the local bread. It was a light, well-baked white bread. Up to that point, Kiechel had only eaten rough, thick, black bread of inferior quality in the villages of Westphalia.

Osnabrück, 1572

This view of Osnabrück is on the same page as the image of Münster in the “Civitates Orbis Terrarum”. The image presents a large city, fortified by walls and a moat. The skyline, as usual, is dominated by multiple churches. The church spires are very narrow and extremely tall. They are likely somewhat exaggerated by the artist, pointing out from the sea of roofs towards the sky. The entire image seems to be a slightly idealised depiction, but that was common for the “Civitates”.

Kiechel remarked that he liked the local bread of Osnabrück. The quality of bread in early modern Germany varied a lot. Bread was a status symbol. Eating white bread was a sign of wealth. Its production was the most labour-intensive, as the flour had to be sieved to remove chaff and improve the texture of the dough.

Dark bread, by contrast, was the staple food for most common people. It could be made from various grains, such as rye or barley. The flour was not as carefully processed as wheat flour for white bread. In times of war or famine, it was not uncommon to use acorns, peas or other available ingredients to supplement the dough. The rough, thick, black bread Kiechel mentioned was probably typical in the villages of Westphalia. With the ongoing Cologne War, its contents were presumably a mixture of whatever ingredients were available at the time.

A Freezing Journey

Samuel Kiechel spent 3 January in Osnabrück because heavy snow had started to fall. The next day, he left in the vehicle of a carter who had delivered goods from Bremen to Osnabrück and was now on his way back. The weather was freezing, and the snow on the road was deep. However, a track had been carved by other carts, making progress easier. Kiechel arrived in a small town he called För after nightfall.

The place is somewhat difficult to identify. It could be Vörden (Neukirchen-Vörden), twenty-two kilometres north of Osnabrück. But Kiechel wrote that För was a small town. Vörden is merely a hamlet. The other option would be Vechta, fifty kilometres north of Osnabrück. However, the distance is quite far for a journey along snow-covered roads. Vechta is also too close to the next destination, Wildeshausen.

After spending the night in För, our traveller continued his journey on the back of the cart. They drove in a convoy with various other vehicles. Snow had begun to fall again, covering the tracks. The carters had difficulty following the road and would repeatedly drive into high drifts of snow that reached the horses’ bellies. Progress was very slow.

Kiechel, sitting in the back of the cart, was freezing. He thought about getting off and walking for a while to warm up. But he did not dare. He was afraid of getting stuck in the deep snow and falling behind.

Winter clothing in the sixteenth century typically included fur-lined items such as boots, gloves or cloaks. Samuel Kiechel did not mention whether he had purchased winter gear. Nonetheless, sitting for hours in a cart that was most likely open to the wind and snow, it would have been impossible to prevent the cold from seeping in. Kiechel knew that walking might have helped keep him warm, but he judged he would not have been able to keep up, and the carters, also feeling the cold, would not wait for him. The situation threatened the well-being of our traveller, and it grew more serious as night fell.

At midnight, the convoy arrived in Wildeshausen. The carts had to wait outside for a long time until someone opened the gate. When our traveller got off the cart, he was frozen stiff from the cold and could hardly stand. He had difficulty finding an inn. Many of the carters lived in this town and simply went home. Eventually, Samuel found someone who pointed him in the direction of the mayor’s house. The house was also a tavern, and after knocking on the door for a long time, he was allowed inside. Kiechel wrote that he lay down on a bench close to the fire and slowly began to warm up again.

The next day, the weather worsened. With all the wind and snow, none of the carters dared to leave, and Kiechel had to stay in Wildeshausen. But the following day was much calmer, and the convoy with our traveller on board set off. The road was deeply covered in snow, and the horses pulled the carts with incredible difficulty. Eventually, they reached Delmenhorst. From there, an open road led to Bremen.

The convoy arrived in Bremen in the evening. Because Delmenhorst and Bremen were two cities Kiechel had already visited on his way to London, and he did not mention any additional details about either place.

Return to Hamburg

Samuel spent one night in Bremen and left on 8 January on a sledge with two boatmen and a messenger from Emden. The group stayed overnight in the village of Pennigbüttel, which is now part of the town of Osterholz-Scharmbeck.

The travellers continued the next day to Bremervörde. They had paid for a sledge to take them there, and now tried to persuade their sledge-driver to go further, but he was unwilling. Kiechel and his companions searched for transport in Bremervörde but failed. Eventually, they decided to continue on foot, but without a guide, they quickly became lost.

Two hours after nightfall, the group found an inn near the village of Hagenah. The innkeeper thought they were mercenaries and initially refused entry. After long begging, they were allowed inside. Kiechel was very hungry after walking through deep snow all day, but apart from a few raw herrings, he found no food. He went into the stable and slept there for a few hours.

Long before sunrise, the travellers left the inn and headed for Stade. However, they lost their way again and had to wander through deep snow searching for the road. Due to being lost, the group accidentally walked into swampy terrain. Kiechel wrote that the ground beneath the snow was not frozen but very wet, and water seeped into their shoes. When the bells rang three in the morning, the travellers finally reached the gate of Stade. But since it was still night, they had to wait until morning for it to open. They were freezing, and their feet were wet from the swamp.

Kiechel and his companions did not stay in Stade. They found a man willing to drive them three miles to the Elbe, where boats to Hamburg departed. During winter, boatmen had to be cautious and closely watch the ice on the river. Kiechel noted that the winter was so cold that the river around Hamburg was frozen, and people travelled on it using sledges. The boatmen kept a stretch of water open, and a boat carried them across the Elbe. From there, they walked to Hamburg and arrived in the city the same day.

Illustrations & References

All images are in order of appearance with links to sources on external websites:

- van Plattenberg, Matthieu, Winterlandschap met een dorpsgezicht, 1617 – 1660; Rijksmuseum Amsterdam.

- Mercator, Gerhard, Westfaliae Secunda Tabula, 1595 (Atlas sive Cosmographicae meditationes de fabrica mvndi et fabricati figvra); Library of Congress, Washington DC.

- Osnabrück, in: Braun, Georg, Hogenberg Frans: Civitates Orbis Terrarum (1), Cologne 1593, fol. 22v; Heidelberg University.

- van Ruisdael, Jacob Isaacksz, Winter Landscape, c. 1665; Rijksmuseum Amsterdam.

- van Goyen, Jan, Ice Scene near a Wooden Observation Tower, 1646; National Gallery of Art, Washington D. C.

- Die Reisen des Samuel Kiechel aus drei Handschriften, K. D. Haszler (ed.), Stuttgart 1866, p. 48; Bayerische Staatsbibliothek. ↩︎