“Just when we were about to leave and return to the river, her Royal Majesty stepped out of the palace and into the square with her advisers. She gave audiences, and I could watch her as much as I liked.”1

In London

12 September – 13 November 1585

After visiting London’s major sights, there was one more ‘attraction’ Samuel Kiechel wanted to see: Queen Elizabeth I. This feeling was common among many travellers of that period. Kiechel did not plan to seek an audience with Elizabeth I; his visit was more like that of a modern tourist waiting outside Buckingham Palace, hoping for a glimpse of the Royal Family.

By coincidence, while our traveller was in London, a new Lord Mayor was inaugurated. Kiechel observed the celebrations and documented his experience.

Chasing the Queen

One highlight of a visit to England in the late sixteenth century that travellers would not want to miss was the Queen. On 8 October, Kiechel and ten other German travellers, many of whom were noblemen, travelled by boat to Richmond Palace. The palace, located to the west of London and close to the Thames, was described by the traveller as old and poorly constructed. Kiechel had heard that Queen Elizabeth I was expected to travel to Richmond, so he went there to see her.

The trip to Richmond Palace marked Kiechel’s third attempt to see the Queen. He had previously visited Nonsuch Palace, where he had only been able to watch her from such a great distance that he felt he had not seen her at all.

Nonsuch Palace, 1599

While the “Civitates Orbis Terrarum” primarily features views of cities, an image of Nonsuch Palace is in volume five and Richmond in volume six. Nonsuch Palace is depicted within its surrounding countryside. In the foreground of the image is a road that presumably leads to the palace. On the road, the artist has drawn a carriage guarded by soldiers and horsemen. The carriage is richly adorned. This little scene possibly represents the arrival of the Queen at Nonsuch Palace. The Palace, built during the reign of Henry VIII, was demolished in the late seventeenth century, and no trace of it remains today.

In contrast, the view of Richmond Palace is small and less elaborate. It depicts only the building with the Thames River in the foreground.

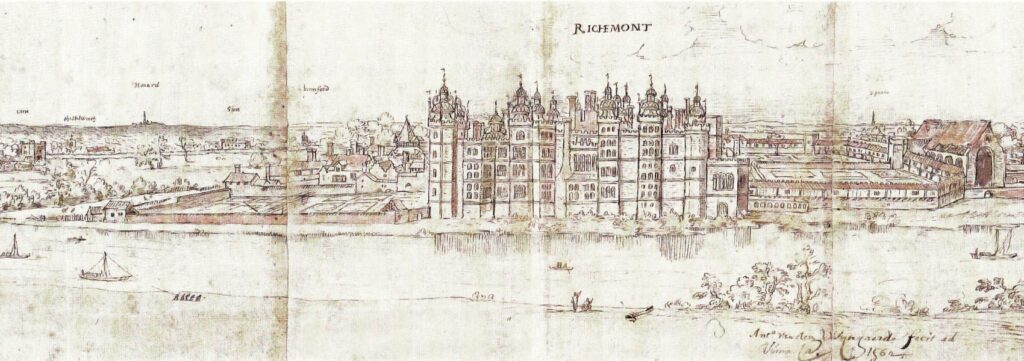

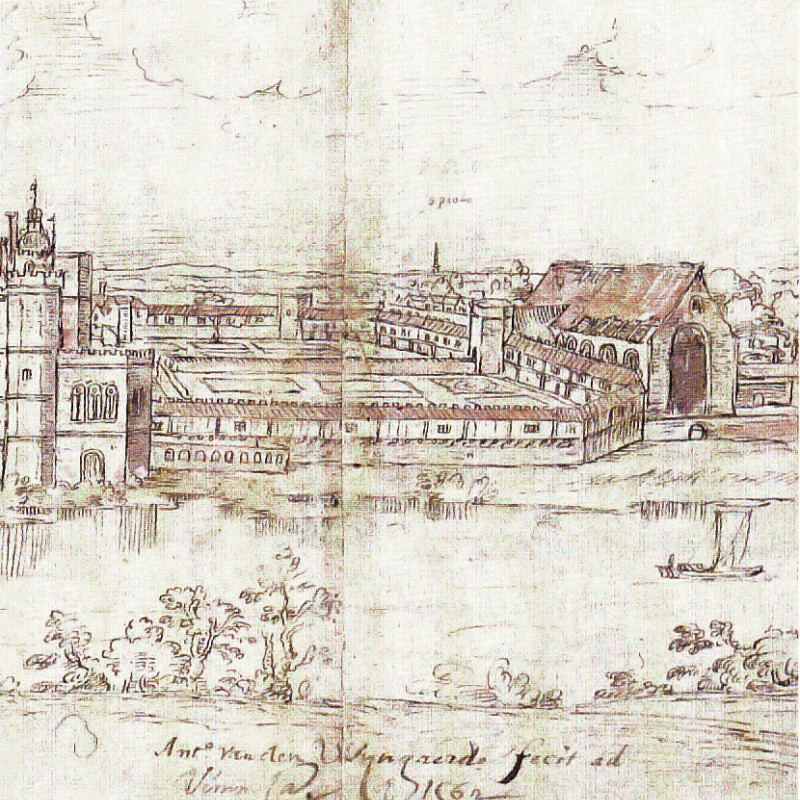

However, the Flemish artist Anton van den Wyngaerde has created two sketches of Richmond Palace. Both sketches are profile views. The first image was drawn from the riverfront, illustrating the Thames in the foreground and the palace on the opposite bank.

The second image offers a panoramic view from the northeast, showcasing the main palace buildings, walls, and surrounding houses. Both views are accessible in the digital collection of the Ashmolean Museum, Oxford.

In Richmond, Samuel Kiechel could finally observe the Queen up close. Elizabeth I arrived in the evening with her maids and advisers, while Kiechel and his companions watched them exit the coach and enter the palace.

On Sunday (10 October), Queen Elizabeth was supposed to attend church. The church was located within the palace grounds, and everything was arranged for Mass. The Queen’s guards lined the path from her chamber to the chapel. Kiechel hoped he might catch a glimpse of her there, but Elizabeth did not appear. Instead, he noted: Her guards were all English and dressed similarly. They wore scarlet-red tunics with a rose embroidered in gold on their chests and backs. They were impressive, strong and tall men of a stature rarely found elsewhere.

English Yeoman of the Guard, 1577

In the afternoon of the same day, just as Kiechel and his companions were about to depart, Queen Elizabeth I emerged from the palace and walked into the plaza in front of it. Her advisers accompanied her, and she conducted audiences and received supplicants. Van den Wyngaerde’s panorama of the palace might offer some insight into where this event took place.

Queen Elizabeth I

Samuel Kiechel could now observe the Queen as much as he wished. He was close enough to witness an audience she gave to the owner of a ship from Hamburg. As far as Kiechel understood, English ships had confiscated the German ship’s goods at sea. The man knelt before the Queen and presented his request. Kiechel could hear the Queen ask if the man spoke English, and then pose the question again in French. However, the man did not understand her and merely shook his head, prompting the Queen to pass his request to one of her advisers.

Many people, both men and women, had gathered around the plaza. As the Queen walked past them, they fell to their knees, lifted their hands, and cried: “gott sauue te genue” (God save the Queen). Kiechel translated it as: “God give our queen a long life.”2 The traveller also noted that it is customary for even a person of noble birth to kneel when speaking to the Queen.

When Elizabeth returned to the palace, Kiechel and the other travellers made their way to the river to take a boat back to London. They arrived in the city late in the evening.

Elizabeth was not the first queen of England; her half-sister Mary had ruled the island briefly before her. Still, for travellers from the continent, having a female regent govern independently and successfully for such a long time was unique and became an attraction for visitors.

As for following the Queen around, hoping to catch a glimpse of her, this was quite a rational approach. Without modern media, rulers had to manifest their authority, power and loyalty by being visible. Representation was key. To achieve this, various ceremonies, rules and rituals were developed. In the Middle Ages, kings were rarely sedentary and often travelled from one castle or city to the next. The purpose was to be seen and present, displaying power and authority directly and immediately.

Institutionalisation, increased literacy and other developments meant that rulers tended to travel less and instead maintain their court permanently in a city that became the capital. Power and authority began to be displayed through elaborate court procedures, lavish palaces and established institutions. However, travelling and personal visibility remained pertinent ingredients. Kiechel was fascinated by seeing the kings and queens of the places he visited. He was successful in this pursuit, as seen with Rudolf II in Prague3 or Elizabeth I.

Queen Elizabeth I did not maintain a permanent court. Instead, she travelled about, being hosted by noblemen and courtiers or visiting her various palaces, such as Nonsuch and Richmond. As a queen, she could not fulfil all the requirements and expectations associated with a ruler, including leading her troops into war. Isolating herself in one of her palaces would have limited her authority and effectiveness as a ruler by making her reliant on her advisers and somewhat distant royal proclamations. Being present and visible to the people was a means to bolster loyalty.4 Part of this ritual of public presence included, according to the observation of Samuel Kiechel, walking outside the palace with her advisers, meeting supplicants, and receiving the adulations of her subjects.

The Lord Mayor’s Show of 1585

On 29 October, Samuel Kiechel observed the induction of the new Lord Mayor of London and provided a relatively comprehensive description of the event. However, it must be emphasised that Kiechel was merely an observer and had a limited understanding of what he saw. He did not speak English and could therefore not ask for explanations. His description may be patchy and inaccurate.

The position of Lord Mayor of London has existed since the twelfth century. Representatives of the livery companies elected a new mayor to serve a single one-year term. To be eligible, a candidate must have served as sheriff of the city and be an alderman of one of London’s wards. The Lord Mayor of London, whose inauguration Samuel Kiechel witnessed, was Wolstan Dixie, a member of the Skinners’ Company and alderman of Broad Street Ward.

A public parade and festivities accompanied the inauguration. The so-called Lord Mayor’s Show became one of the grand yearly events in sixteenth-century England and continues to be so today. While Samuel Kiechel did not mention locations apart from the Thames and Westminster Abbey, the procession likely went along Cheapside. This broad street in the heart of London, with its representative houses, was typically used for such events.5

Kiechel wrote: After his election, the new Lord Mayor would take an oath in the church of Westminster in front of various important men, but, to Kiechel’s surprise, not the queen. The event involved many ceremonies. First, the predecessors in office assembled at the new Lord Mayor’s house in the morning. Together (Kiechel wrote they were twenty-one men), they rode through the city towards the river. They all wore identical scarlet-red tunics lined with marten or sable pelts. In front of the new Lord Mayor and his predecessors walked the masters of the livery companies. They wore long black robes, similar to the robes of the noblemen of Venice. Each master had one flap of his robe slung over his left shoulder, which was half red and half black.

Beside and in front of the mayors and masters walked six men dressed in black velvet, wearing golden chains. Each of the six men carried a long black staff to clear a path so the many people watching would not hinder their progress. Fifteen trumpeters marched in three rows, accompanying the parade.

Kiechel noticed a large structure carried in the procession. To our traveller, it resembled a small summer house. Twelve children, both girls and boys, were seated around its four sides. They were richly dressed and adorned with gold and jewellery. The structure was decorated like a garden with flowers, roses and other beautifully crafted elements. The people bearing it were concealed by the exquisite textiles draped down to the ground. Additionally, something that appeared to Kiechel as a large camel was carried in front of the structure. It was so skillfully made that, from a distance, it looked like a real camel. There were more customs and rituals to observe, but Kiechel chose not to write about them as he wished to keep his description brief.

The strange structure Kiechel observed was part of the pageant accompanying the procession. A pageant is an elaborate theatrical performance set in a lavishly constructed scene placed on a float to accompany a procession. The English poet and playwright George Peele wrote this performance. His text “THE DEVICE of the Pageant borne before Woolſtone Dixi LORD Maior of the Citie of London. An. 1585. October 29”6 is one of the earliest pageants that have survived.

Peele sets the scene: “A Speech ſpoken by him that rid on a Luzarne before the Pageant apparelled like a Moore.”7 A “luzarne” was a lynx, an animal whose fur was highly valued and expensive.8 It might have been playing on Dixie being of the Skinner’s Company. “Apparelled like a Moore” meant the person was dressed in a ‘Moorish’ style. The term presumably encompassed anything that appeared vaguely exotic and reflected how the people of London imagined North African or Muslim fashion.

The twelve children Kiechel mentioned were also part of the performance:

“Spoken by the Children in the Pageant viz. London.

NEW Troye I hight whome Lud my Lord ſurnam’d,

London the glory of the weſtern ſide:

Throughout the world is louely London fam’d,

So farre as any ſea comes in with tide.

Whoſe peace and calme vnder her Royall Quéene:

Hath long bin ſuch as like was neuer ſéene.”9

Following this, various allegorical figures and personifications — such as Loyalty, the Country, the Thames, a soldier, a sailor, and three nymphs — make an appearance to praise London. I doubt Samuel Kiechel understood any of it. However, even without knowing what the characters in the pageant were saying, it was still an impressive event to witness.

Kiechel continued his description: The procession moved to the Thames, and upon arriving at the river, the new Lord Mayor and his predecessors boarded a beautifully decorated ship. Each livery company had a boat, and many more vessels journeyed up the Thames to Westminster Abbey.

At Westminster, everyone disembarked. The former mayors, guild leaders, and others entered the church in pairs. The documents upon which the new Lord Mayor had to take his oath were presented to him inside. This part of the ceremony did not take place in public. It was done in a special corner of the church.

After taking the oath, the new Lord Mayor exited the church. A sword and a sceptre were carried in front of him. Kiechel interpreted the two items as symbols of the new Mayor’s power to punish evil.

From Westminster Abbey, the procession returned to the river. The people boarded the various ships to journey back downriver to London. Among the many ships was also a small warship. It was richly decorated, painted, and filled with people. The warship fired multiple gun salutes and used a great deal of powder that day.

When the ships arrived in London, the new Lord Mayor returned to his residence, where he hosted a grand banquet. Many men and women, noblemen and strangers, participated in the feast as if it were an open celebration. The banquet continued into the afternoon, and afterwards, the new Lord Mayor, along with other dignitaries and the guild leaders, rode to Westminster Abbey for Vespers (evening prayer). After Vespers, the attendees listened to what Kiechel called “treffenliche musica” (splendid music = probably Evensong), which was performed in praise of the new mayor. Following this, he was escorted back to his residence.

Kiechel concluded his description by stating that it was an impressive yet costly event.

Illustrations & References

All images are in order of appearance with links to sources on external websites:

- Hollar, Wenceslaus, Gezicht op Richmond Palace in Surrey, 1638; Rijksmuseum Amsterdam.

- Nonsuch Palace, in: Braun, Georg, Hogenberg, Frans, Civitates Orbis Terrarum (5), Cologne 1599, fol. 1v; Heidelberg University.

- van den Wyngaerde, Anton, Richmond Palace, 1562; Wikimedia Commons.

- de Bruyn, Abraham, Engelse Yeoman of the Guard, 1577; Rijksmuseum Amsterdam.

- Anonymous, Portrait of Elizabeth I, Queen of England, 1550-1599; Rijksmuseum Amsterdam.

- Alley, Hugh, A caveatt for the citty of London, or, A forewarninge of offences against penall lawes [manuscript], 1598, fol. 13r; Folger Shakespeare Library, Washington DC.

- Alley, Hugh, A caveatt for the citty of London, or, A forewarninge of offences against penall lawes [manuscript], 1598, fol. 8r; Folger Shakespeare Library, Washington DC.

- Die Reisen des Samuel Kiechel aus drei Handschriften, K. D. Haszler (ed.), Stuttgart 1866, p. 25; Bayerische Staatsbibliothek. ↩︎

- Ibid., p. 26. ↩︎

- Ibid., p. 3. ↩︎

- Mortimer, Ian, The Time Traveller’s Guide to Elizabethan England, London2021, pp. 39-46. ↩︎

- Mortimer, Time Traveller’s Guide, p. 34. ↩︎

- Peele, George, The Device of the Pageant Borne before Wolstan Dixie Lord Maior of the citie of London. An. 1585, in: J. Jenstad (Ed.), The Map of Early Modern London (Edition 7.0), University of Victoria 2022. ↩︎

- Ibid., fol. 2r. ↩︎

- Phipson, Emma, The Animal-Lore of Shakespeare’s Time, 1883, pp. 30-31; Veale, Elspeth M., The English Fur Trade in the Later Middle Ages, 2003, Glossary, pp. 215-229. ↩︎

- Peele, The Device of the Pageant, fol. 2v. ↩︎