“Half an hour after leaving the city, we met a poor woman from Lünen, our next stop. Without hesitation, she warned us to be cautious because 17 bandits were waiting near the town. They had already robbed two pedlars and even taken their clothes.“1

From Cologne to Münster

25 December 1585 – 01 January 1586

After resting for a few days within the safety of the sturdy walls of Cologne, our traveller, Samuel Kiechel, decided to resume his journey. He had found new companions, a group of merchants heading to Münster in Westphalia. It was winter, and his fellow travellers had told him that walking was safer than riding, so Kiechel had sold his horse. Besides the cold weather, the journey ahead was perilous because of bandits and roving bands of mercenaries.

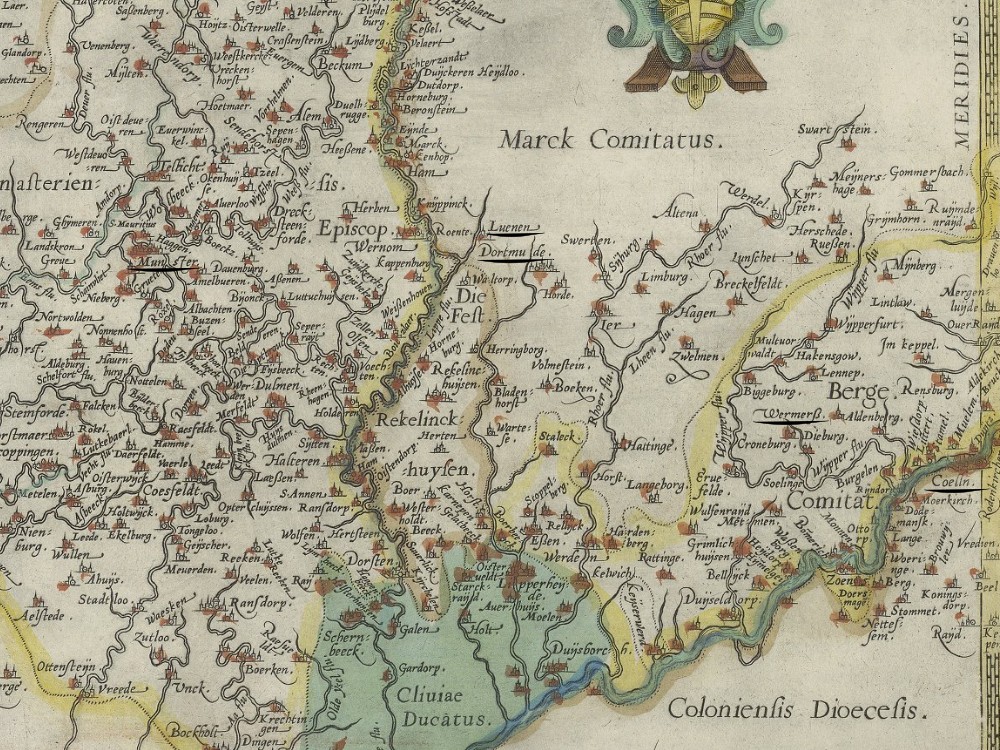

Route from Cologne via Dortmund to Münster (the map is oriented eastward)

From the Rhine River to Dortmund

On 25 December, Samuel Kiechel and his new companions left Cologne. They crossed the frozen Rhine River to Deutz on the opposite bank. From there, the group trudged along a rough path that was covered with a thick layer of snow. No track had been carved into the snow by previous travellers. Progress was slow and tiring.

The villages they passed mainly were destroyed or deserted. The travellers had difficulty finding someone to sell them food to eat at lunchtime. Late in the evening, they arrived in a hamlet called Wermelskirchen. According to Kiechel, the place was in the Duchy of Jülich. It had an inn where they spent the night.

The destruction and devastation the travellers witnessed were a result of the Cologne War. This confrontation was not fought between large armies along a recognisable frontline. A protracted regional conflict, the fighting in the Cologne War was conducted by small mercenary armies through skirmishes, raids and attacks on minor towns. The mercenaries regularly operated for their profit, sacking the places they besieged without regard for civilian lives. Large cities, like Cologne, were safe behind their thick walls. Villages, on the other hand, had no fortifications and lacked the population to defend themselves. As Samuel Kiechel witnessed, those places were plundered and destroyed, or the people decided to abandon their homes.

In the inn in Wermelskirchen, Kiechel and his companions met a pastor who joined the group. The travellers continued their journey the following morning. The path had not improved, and the countryside was not safe. Due to those circumstances, the group walked only three miles to Gevelsberg. After spending the night there, they continued the next day (27 December) and arrived in Dortmund in the evening.

The road from Cologne to Dortmund ran through the Bergisches Land, an area of low mountain ranges, hills, forests and meadows. The route Kiechel travelled via Wermelskirchen and Gevelsberg was a major thoroughfare through this region. A map from 1635 shows the road starting at Mülheim on the Rhine River, along with the surrounding landscape. Due to its role as a frequently used route by armies and mercenaries, it is no surprise that the settlements along this road often suffered attacks.

Map of the Bergisches Land, 1635

Dortmund

Samuel Kiechel’s destination, Dortmund, is located in the Ruhr Area, the largest and most densely populated urban region in modern Germany. The industrialisation of the nineteenth century significantly accelerated urban growth, but in the sixteenth century, it was still mainly agricultural. By passing through the Bergisches Land, Kiechel’s route skirted the edges of this area.

According to our traveller, Dortmund was a small, imperial city. A fair was scheduled for the day after our traveller’s arrival. However, as Kiechel had already noted, the countryside around Dortmund was unsafe. Mercenaries from both sides in the Cologne War patrolled the land, viewing every stranger as a threat.

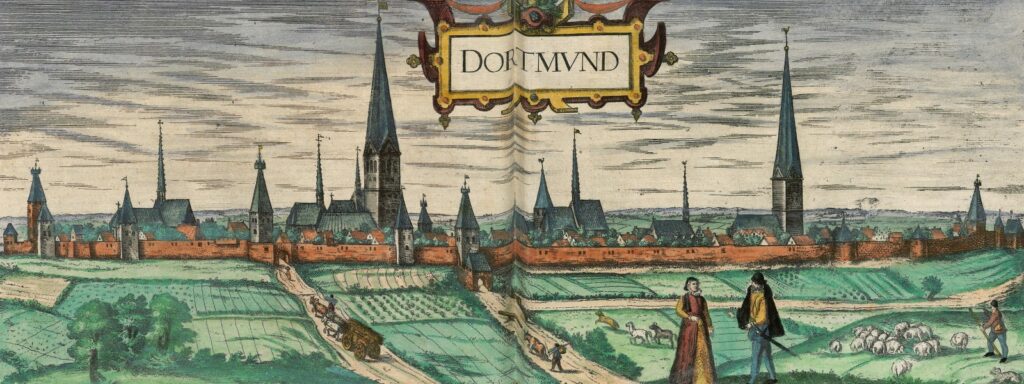

A view of Dortmund appears in volume four of the “Civitates Orbis Terrarum” and supports Kiechel’s sparse observations. The city is not particularly large but is fortified, with two large churches dominating the skyline. Unlike Kiechel’s description, the surrounding area appears peaceful, with fields and pastoral scenes — a shepherd with his flock, a cart transporting wood to Dortmund.

Dortmund was situated along a significant trade route that connected the Lower Rhine in the west to the Elbe River in the east. However, in the late sixteenth century, the city suffered from the fallout of the Eighty Years’ War in the Netherlands and regional conflicts. With the countryside unsafe and merchants threatened by bandits and mercenaries, Dortmund’s prosperity declined. Samuel Kiechel’s journal captures the experience of travelling through this region.

The Dangers Around Dortmund

The travellers left Dortmund on 28 December. The moment the group had left the gate, they noticed a tall and strong man following them. The man carried only a staff. Kiechel and his companions stopped and asked him where he was going. The man told them that he was travelling to Lünen. As this was the next destination of the group, Kiechel offered the man a few coins if he was willing to carry his bag. He agreed, and they continued together.

Half an hour later, the travellers met a poor woman coming from the direction of Lünen. Without being asked, the woman advised them to be careful. Seventeen bandits were lying in wait close to Lünen. The bandits had already ambushed two traders heading to the fair in Dortmund. They robbed them and even took their clothes. Upon hearing this, Kiechel and his companions were shocked and worried. But the man they had met outside of Dortmund encouraged the travellers to continue on their route.

They walked on and met another woman who also warned them about the bandits near Lünen. Now, the travellers were fearful of continuing and went to the next tavern located on the roadside to reconsider their options. In the tavern, the locals told them that the bandits had been in this place the previous night. They had been eating and drinking and left in the morning.

Not far from the tavern was a small hamlet. Two or three of the travellers went there to ask the Schultheiß (head of the village) for advice. He offered the travellers a guide to lead them by a different and slightly longer route to Lünen.

Back in the tavern, the travellers told the man they had met outside of Dortmund that they would take a different route. They asked him to come along, but the man refused and became obstinate. Kiechel and his companions concluded that he was a spy for the bandits and would have led them into an ambush. An argument broke out between the travellers and the man. Unfortunately, the innkeeper and his servants joined in and sided with the man. When they threatened the travellers with pitchforks and shovels, the group quickly left.

Reading Samuel Kiechel’s journal, to our traveller, the line between mercenaries, bandits and peasants in a dangerous region seems to have been ambiguous. It was not unusual for people in desperate situations to make a living by openly or secretly collaborating with criminals. Samuel Kiechel expressed this suspicion earlier while still crossing the Low Countries. With word-of-mouth being the main way of sharing local news, it was easy for personal opinions, stereotypes and exaggerated stories to foster suspicion, mistrust and fear, which could then grow into outright hostility.

Kiechel’s description of his stopover in the roadside inn suggests that the man they had met outside Dortmund was indeed spying for the bandits who were supposed to wait around Lünen. He might have been tasked with leading the travellers straight into an ambush. Kiechel mentioned that the same group of bandits had spent the previous night in this inn, eating and drinking without interference from the innkeeper. In the about-to-turn-violent argument with the travellers, the innkeeper and his servants supported the man. So, maybe both this lone man and the innkeeper were involved with the criminals.

On the other hand, facing seventeen armed bandits, the innkeeper might not have had a choice but to serve them. The man who had joined the group outside Dortmund might have been upset by being accused by Kiechel and his companions of being a spy. The innkeeper and his staff then supported him because they had heard such accusations before and were tired of being lumped together with bandits.

Whatever the truth was behind this encounter, Samuel Kiechel and his companions were glad to get away from the place. They followed their new guide along a different but safe route. It turned out to be a long detour on a rough path. The track was covered in deep snow, making progress exhausting.

They arrived in Lünen after lunchtime, even though the town was only a mile from Dortmund. The group took a break. After the tiresome trek through the snow, the travellers were hungry. In the afternoon, they continued and walked to Wehren (Werne?), where they spent the night.

The following day (29 December), the travellers walked to Münster. On their way, they were unable to buy any food, and in Münster, they had to search for a long time before finding an inn.

In Münster

Kiechel described Münster as a small but heavily fortified city in Westphalia. It was the seat of a bishopric and had a monastery. Münster was well-built, and many houses had arcades, similar to those found in Padua or Bologna. The arcades allowed the people to cross from one street to another.

An image of Münster is in the first volume of the “Civitates”. The view presents the city as a well-fortified and wealthy place.

Münster, 1572

Münster is an ancient city. It originated from a monastery that had been founded there in 793. In the early eighth century, the Diocese of Münster was established. A settlement formed around the monastery, grew and received city rights in 1170. Münster developed into an important regional economic and political centre and became a member of the Hanseatic League. As the seat of a Diocese, the citizens were in regular conflict with their bishop. Similar to other cities in the Empire, the quest for civic autonomy clashed with the attempts of regional lords to keep their power and privileges.

When the Protestant Reformation spread through the Empire in the sixteenth century, it took its own unique and rather violent path in Münster:

Samuel Kiechel reported: He saw three iron cages built into the tower of the church at the market square. The cage in the middle was positioned slightly higher than the other two. Kiechel learnt that this cage contained the remains of Johan von Leyden, a tailor from Holland. Von Leyden was an Anabaptist and had proclaimed himself king when Münster was under siege. Eventually, the city surrendered due to famine. Von Leyden and his close allies were executed, and their bodies were put into the cages as a spectacle. Kiechel observed that some bones and part of the skull of von Leyden were still there, but nothing remained of the other two bodies.

The event Kiechel described was the Münster Rebellion (1534-1535). The Protestant Reformation did not simply split the church into Catholic and Protestant. Various branches of Protestantism emerged, including Calvinism and Anabaptism.

The Anabaptists were successful among Münster’s Protestants. They managed to drive out and suppress all other confessional strands. Many Anabaptists were Dutch migrants. One of them was Johan von Leiden (1509-1536), who arrived in the city in 1533 and quickly became a leader of the Anabaptist movement. In the same year, the radicalised Anabaptists took control of the city, expelling the bishop and establishing a theocratic reign. Citizens of other confessions were given a choice to convert or leave.

Johan van Leiden

In response to his expulsion, the Bishop of Münster assembled an army and laid siege to the city in 1534. During the siege, von Leyden, by now the sole leader of the Anabaptists, proclaimed himself king of the Kingdom of New Jerusalem. Despite the deprivations of the siege, he established a luxurious court and introduced polygyny. Executions of potential enemies or traitors were commonplace and often carried out by von Leyden himself.

As Kiechel wrote, after a lengthy siege, Münster had to surrender due to famine. When the bishop retook the city, many Anabaptists were killed. Von Leiden and his two deputies were tortured and executed. Their bodies were placed in iron cages that were hung from the tower of St. Lambert’s Church as a warning. The church and the three cages are still there today.

St. Lambert’s Church in Münster

Kiechel stayed in Münster until 1 January. He had to look for new companions to carry on. Additionally, our traveller wanted to buy a horse but was unable to find one for sale. Instead, he decided to hire a farm hand to carry his bag and guide him to his next destination, Osnabrück.

Illustrations & References

All images are in order of appearance with links to sources on external websites:

- Avercamp, Hendrick, Landscape with Houses and Two Windmills along a Road, with Three Fishermen in the Foreground, before 1620; Rijksmuseum Amsterdam.

- Ortelius, Abraham, Theatrum Orbis Terrarum, 1606, fol. 54v; Folger Shakespeare Library.

- Anonymous, Berge Ducatus Marck Comitatus, 1635; Landesarchiv NRW, Signature: RW Karten / RW Karten, Nr. 10001.

- Dortmund, in: Braun, Georg, Hogenberg Frans: Civitates Orbis Terrarum (4), Cologne 1594, fol. 20v; Heidelberg University.

- Anonymous, Studieblad met boerenwagens, vee, landlieden en ruiters, 1600-1700; Rijksmuseum Amsterdam.

- Saftleven, Herman, Zeven mannen, staand, zittend en lopend, 1619 – 1685; Rijksmuseum Amsterdam.

- Avercamp, Hendrick, View of a Country House with Sowers in the Field, c. 1610 – c. 1615; Rijksmuseum Amsterdam.

- Münster, in: Braun, Georg, Hogenberg Frans: Civitates Orbis Terrarum (1), Cologne 1593, fol. 22v; Heidelberg University.

- de Hooghe, Romeyn, Iohannes Bucholdi á Leyda, before 1701; Rijksmuseum Amsterdam.

- Die Reisen des Samuel Kiechel aus drei Handschriften, K. D. Haszler (ed.), Stuttgart 1866, p. 45; Bayerische Staatsbibliothek. ↩︎