“Prague is the capital of the Kingdom of Bohemia, and his Imperial Majesty has his residence there. The city is old and very big. A river flows through it and separates the Lesser Town (where the palace of his Majesty is) from the Old Town. The river is called the Mult, and a beautiful bridge with many arches spans across it.“1

Prague

3 June – 6 June 1585

Prague is a popular destination for travellers. This is not just the case today, but has been in the past. In the late sixteenth century, the city was flourishing. Emperor Rudolf II had made it his residence, and as the imperial capital, Prague attracted investors, artists, and scholars. For Samuel Kiechel, it was a good place to recuperate after the long hike through the Bohemian Forest.

Arriving in Prague

Samuel Kiechel approached Prague from the southwest and was greeted by an impressive sight. The imperial city sits between hills in a valley carved by the Vltava.

The river divides Prague into two parts. The Lesser Town (Malá Strana, Kleinseite) is on the western bank, with the Palace of the Emperor (Prague Castle) and St. Vitus Cathedral on a hill above. The Old Town of Prague is on the opposite side of the Vltava. Kiechel took his accommodation in the Lesser Town in the inn “Zur Zuckerbäckerin” (At the Confectioners).

According to the text in the “Civitates Orbis Terrarum”, a significant collection of city views and maps from the sixteenth century, Old Prague is on a large plain and features many impressive buildings like the courthouse, the market, the city hall and the Karolinum (Charles University). The University of Prague was founded in 1347 by the King of Bohemia and Holy Roman Emperor, Charles IV. It has an exquisite library and magnificent colleges. The university was devastated by the pointless raging of the Hussites, but rebuilt during the reign of the Emperors Ferdinand and Maximilian II (grandfather and father of the current Emperor Rudolf II).2

A View of Prague in the Sixteenth Century

Typical for the early stages of Samuel Kiechel’s journey, our traveller’s description of Prague is short despite spending four days in the city. But sixteenth-century Prague was an important metropolis and the residence of Emperor Rudolf II. A selection of city views from the early modern period are therefore available to illustrate and supplement Kiechel’s experience.

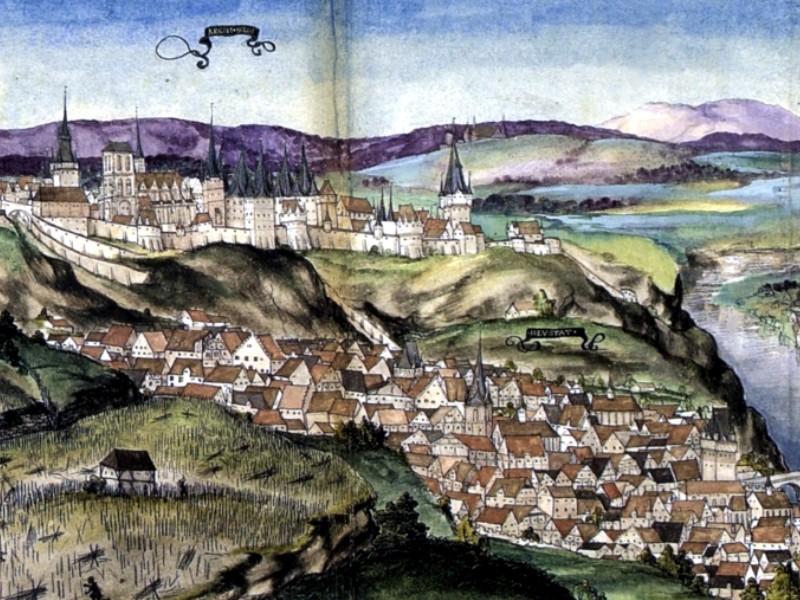

The first realistic depiction of Prague is from 1537. The image is from a collection of drawings made during the journey of Otto-Henry (1502-1559), Elector Palatinate. Otto-Henry had travelled quite extensively in his younger years. In 1536, he went on one more journey. He travelled from Neuburg on the Danube through Bohemia and Silesia to Kraków and returned home via Berlin and Leipzig.3

Prague: Lesser Town and Prague Castle, 1537

An artist accompanied Otto-Henry on this journey and made preliminary sketches of the places they visited. The name of the artist, or possibly artists, is unknown. After Otto-Henry’s return, the sketches served as templates for views of the cities. The views were first drawn in ink and then coloured with watercolours.

The style of the city views is consistent throughout the collection. All cities are shown in a profile or low oblique view and embedded in the surrounding landscape. While the artist depicted them as lifelike and realistic, the landscapes are mostly fictitious and contain recurring set pieces. The high mountains in the background of the view of Prague are, for example, figments of the artist’s imagination.4

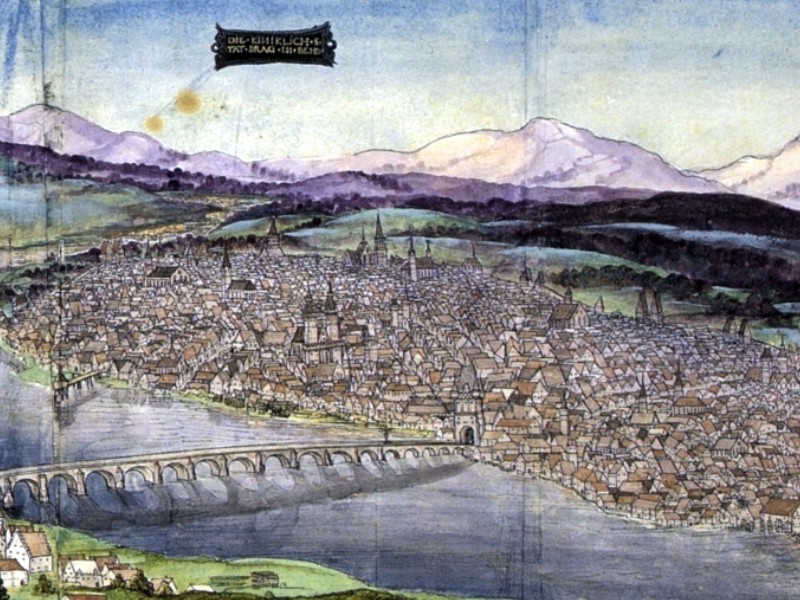

The image of the city itself — the sea of roofs on the right side of the river and the majestic palace on the left — pays tribute to the wealth and power of sixteenth-century Prague at the time.

Prague: Bridge and Old Town, 1537

A particular focus of the image is on the bridge across the river. The artist depicted the river as uncharacteristically calm, and the bridge is mirrored in the water below. It emphasises its size and construction. The bridge still exists today. It was renamed “Charles Bridge” in the nineteenth century. Kiechel was impressed by it and mentioned its many arches.

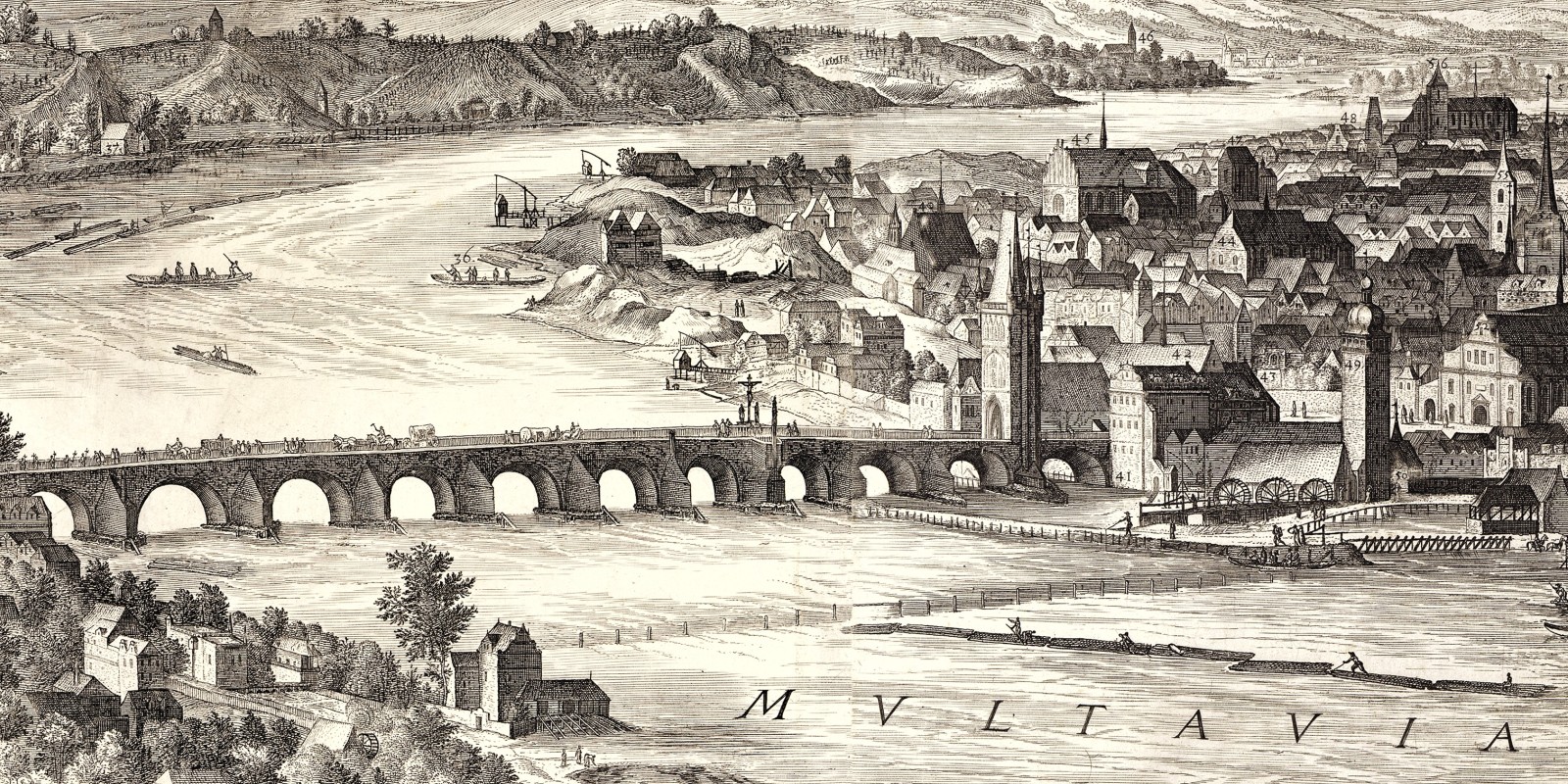

With just one bridge crossing the river, ferries connected parts of the Lesser Quarter and the Old Town of Prague. Aegidius Sadeler published an impressively detailed view of the Bohemian capital in 1606. A closer look shows the bridge and the traffic on it in detail. Ferryboats and various rafts are also visible. The river Vltava, just like the Danube, was used to transport wood from the forests upstream to the city. You can see two rafts made from logs in the foreground.

Prague and bridge across the Vltava, 1606

Prague under Emperor Rudolf II

During his four days in the Bohemian capital, Samuel Kiechel visited Prague Castle. At the time, the castle was the primary residence of the Emperor of the Holy Roman Empire, Rudolf II of Habsburg (1552-1612). Rudolf had been crowned King of Bohemia in 1575 and Emperor in 1576. In 1583, he moved the imperial court from Vienna to Prague.

Emperor Rudolf II, 1594

Rudolf II is considered a weak and ineffective ruler. His ambitions collided with the political reality of increasing religious tensions in the Empire. Due to his indecisiveness and passivity, a long and exhausting war with the Ottoman Empire and his refusal to marry and thereby secure his succession, Rudolf’s brother Matthias rebelled. Supported by other members of the Habsburg Family, Matthias stripped Rudolf of his powers. By 1611, Rudolf was still Emperor but had lost all influence and died soon after.

However, Rudolf was known as a great patron of the arts and sciences. Influenced by Humanist ideals, he was tolerant towards Protestants and Jews. Rudolf was interested in natural philosophy, astronomy, astrology, and alchemy. At his court in Prague, he surrounded himself with artists, poets, mathematicians, and astronomers like Tycho Brahe and Johannes Kepler. His interest in and dedication to cultural and intellectual matters would have been palpable in every corner of the city.

Rudolf was not the first Emperor to choose Prague as his residence. In the fourteenth century, the city had been home to the court of Charles IV (1316-1378). Prague flourished under Charles’ rule. He ordered the destroyed Prague Castle to be rebuilt, and the construction of the New City started. The stone bridge across the river was built during Charles’ reign to reconnect the Lesser Quarter with the Old Town. A flood had destroyed the previous bridge in 1342. Charles founded Prague University. He elevated the Diocese of Prague to an Archdiocese, and the construction of St. Vitus Cathedral also began during his reign.

Charles IV was from the House of Luxembourg. The shift of power from the Luxembourgs to the Habsburgs after the death of Charles’ son Sigismund in 1437 meant that Prague lost its prestigious position as home to the imperial court. The city flourished for a second time when Rudolf II made Prague Castle his residence.

Sightseeing in Sixteenth-Century Prague

Samuel Kiechel mentioned only a few observations about Prague Castle in his journal. He was impressed by the enormous size of the palace’s main hall and its ribbed vault. The vault covered the entire hall without the need for supporting pillars in between.

The hall is the Vladislav Hall. It was built between 1493 and 1502 and was one of the largest secular halls in Europe at the time. It is among the structurally most complex late medieval constructions. The hall is about sixty meters long, twenty meters wide and fifteen meters high.

Vladislav Hall, 1607

Kiechel visited the church where the Emperor went to worship. It had been built close to the palace, and a passageway connected both buildings. Our traveller even watched Emperor Rudolf II go to church. The church was St. Vitus Cathedral.

Prague Castle and St. Vitus Cathedral, 1606

Throughout his journey, Samuel Kiechel repeatedly displayed an interest in seeing members of the noble and ruling families of the places he visited. But he did not seek audiences and was content to watch them. His interest appears similar to the modern fascination with celebrities and royalty.

Finally, Kiechel visited the imperial stables where he saw beautiful Turkish, Neapolitan and Spanish horses. Rudolf II had ordered the construction of the stables in 1583. To make room, he had a section of the medieval ramparts on the northern side of the castle demolished.

The imperial garden and zoo were north of the castle and about half an hour from the city. Kiechel visited them and wrote: The area consists mainly of woodland, and a wall surrounds it. Within the garden is a lake where the animals drink. Beside the lake are pleasant meadows. At the entrance is a beautiful summer palace.

Prague from the north, 1599

The Royal Garden (Královská zahrada) was a Renaissance-style garden. Emperor Ferdinand (1503-1564), the grandfather of Rudolf II, had commissioned it. Construction of the garden was completed in 1534. Ferdinand built the Summer Palace there for his wife Anna of Bohemia and Hungary (Queen Anne’s Summer Palace, finished in 1560). The nobility used Summer palaces as a seasonal retreat. Kiechel regularly mentioned such places. They were worthwhile attractions for our traveller to visit.

As for the zoo, Rudolph II had a lion house built in the garden in 1583 (Löwenhof, Lví Dvůr). As the name suggests, it housed lions and other exotic animals.

Samuel Kiechel left Prague on the 7 June by carriage to travel to the Duchy of Saxony.

Illustrations & References

All images are in order of appearance with links to sources on external websites:

- Prague Castle, in: Braun, Georg, Hogenberg: Frans, Civitates Orbis Terrarum (5), Cologne 1599, fol. 49v; Heidelberg University.

- Prague, in: Braun, Georg, Hogenberg, Frans: Civitates Orbis Terrarum (1), Cologne 1593, fol. 29v; Heidelberg University.

- View of Prague from the Journal of Otto-Henry, Elector Palatinate, 1537; Wikimedia Commons.

- Wechter, Johannes: View of the City of Prague, 1606; Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York.

- Custos, Dominicus, Portret van keizer Rudolf II, 1594; Rijksmuseum Amsterdam.

- Aegidius Sadeler, Interior View of Vladislav Hall at Prague Castle during the Annual Fair, 1607; Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York.

- Wechter, Johannes: View of the City of Prague, 1606; Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York.

- Prague Castle from the north, in: Braun, Georg, Hogenberg, Frans: Civitates Orbis Terrarum (5), Cologne 1599, fol. 49v; Heidelberg University.

- Die Reisen des Samuel Kiechel aus drei Handschriften, K. D. Haszler (ed.), Stuttgart 1866, pp. 3-4; Bayerische Staatsbibliothek. ↩︎

- Braun, Georg, Hogenberg, Frans: Civitates Orbis Terrarum (1), Cologne 1593, fol. 29. ↩︎

- Pabel, Angelika, Pleticha-Geuder, Eva, Schmid, Anne, Schmidt, Hans-Günther (eds.): Reise, Rast und Augenblick. Mitteleuropäische Stadtansichten aus dem 16. Jahrhundert, Ausstellungsführer, Dettelbach 2002. ↩︎

- Pabel et al. (eds.): Reise, Rast und Augenblick, pp. 8-18, 44. ↩︎