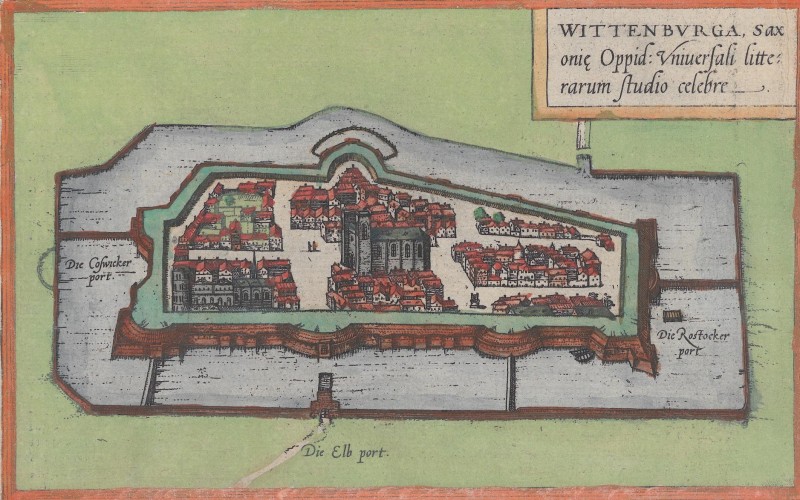

“Wittenberg is in Saxony and has a university. It is close to the Elbe, and a wooden bridge leads across the river. On the bridge, travellers on foot or horseback pay a toll.“1

From Leipzig to Wittenberg

16 June – 17 June 1585

Unlike today, religion was deeply woven into the fabric of sixteenth-century life, shaping not just society but the everyday experiences of a traveller. In those times, religious tolerance was an exception rather than the rule, and any stranger would have been wise to keep their beliefs private.

On the other hand, the immediacy of events that changed the face of Christianity was still vivid. To our imagination, visiting as a Protestant the city where the Reformation started just over half a century ago, and where the great reformer Martin Luther had lived and worked, must have been a powerful experience.

The Road to Wittenberg

Samuel Kiechel departed Leipzig on 16 June, accompanied by a messenger from Silesia. The two men walked to the small town of Bad Düben on the river Mulde in the land of Meissen (district of Meissen in the Electorate of Saxony). They arrived in the evening. It rained throughout the day, leaving both men soaked. Unable to find an inn in the town, they had to spend the night, as Kiechel wrote, ‘on straw’. His mention of the bedding’s quality suggests that our traveller had not found regular accommodation and was forced to sleep in a stable, barn or shed.

It rained throughout the night and into the morning. Kiechel and his companion hesitated to continue in such weather, waiting until noon before departing Bad Düben. The road was rough and soggy, winding through dense forests.

Kiechel frequently commented on the state of the roads. The definition of a road in the early modern period was broad, encompassing dirt tracks as well as cobbled and well-maintained pathways. Most roads were constructed for short-distance travel and the transport of goods between towns and villages in a region. An interconnected, long-distance network of roads, as we know it today, had not yet been established in the sixteenth century. Road construction and maintenance were costly, and high-quality roads were typically found only around the wealthier cities. Wet weather often turned the roads without a solid surface into mires as the water accumulated in the tracks and ruts, turning the ground soggy.

In Wittenberg

The two travellers arrived in Wittenberg on the evening of the same day. Samuel Kiechel’s comments about the town are characteristically sparse. He wrote: Wittenberg is in Saxony, has a university, and the river Elbe flows past it. A wooden bridge crosses the river, and those who use it pay a toll.

Founded in the late twelfth century, Wittenberg is now best known as the place where the Protestant Reformation began. However, the town had also served as the residence of the Prince-Electors of Saxony until 1547. The House of Wettin, which held the title of Prince-Elector of Saxony, split into two branches in 1485 (Treaty of Leipzig). The Albertine line received the Margraviate of Meissen and continued to rule from Dresden. The Ernestine line retained the electoral dignity along with the title of “Duke of Saxony”, but needed to find a new residence. Ernest (1441–1486), Prince-Elector of Saxony, chose Wittenberg.

Under the rule of Ernest’s son, Frederick III (1463–1525), Wittenberg flourished. He had the old castle demolished and a new, modern palace built. The Schlosskirche (Castle Church) was renovated and connected to the palace. The Duke possessed one of the most extensive collections of relics and invited artists like Lucas Cranach (1472–1553) to his court. In 1502, Frederick founded the University of Wittenberg, where, ten years later, Martin Luther (1483–1546) would be awarded his doctorate and become chair of theology.

Wittenberg, 1575

The view of Wittenberg from the south in the “Civitates Orbis Terrarum” is poor. It is small and lacks detail. In the centre is the Town and Parish Church of St. Mary’s, where Mass was celebrated for the first time in German rather than Latin in 1521.

A better view of Wittenberg is found in the journal of Otto-Henry, Elector Palatine.2 The city is shown in profile from the south. The Elbe River is in the foreground, with the wooden bridge mentioned by Kiechel crossing it. The castle, Castle Church, and St. Mary’s Church dominate Wittenberg’s outline. Most of the prominent buildings in this view were either built or rebuilt during Frederick III’s reign. Samuel Kiechel, arriving from the south, was most likely greeted by this scene.

Wittenberg, 1537

Wittenberg and the Protestant Reformation

Samuel Kiechel was a Protestant, or as he describes himself, a Lutheran. From our modern viewpoint, and considering the intense religious climate in the Empire, Wittenberg would have been a significant stop on our traveller’s itinerary. However, if that were the case, he did not mention it. Perhaps the city’s importance to the Reformation is a modern perspective, gaining more relevance only once the tensions between different Christian branches had eased.

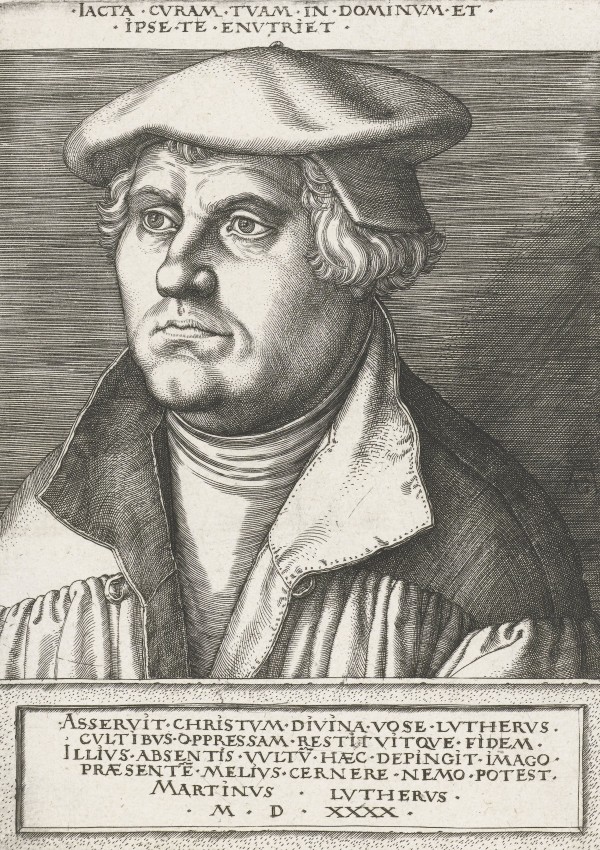

Martin Luther, 1540

Around seventy years prior to Kiechel’s visit, Wittenberg had become the centre of the Protestant Reformation when Martin Luther posted his Ninety-five Theses in 1517. The Theses mainly criticised the sale of indulgences. Luther challenged the claim made by preachers that people could buy forgiveness and absolution for their sins. He maintained that forgiveness could not be purchased and could only be granted by God.

Luther sent his Theses to Albert of Brandenburg (1490–1545), the Archbishop of Mainz and Magdeburg, since Wittenberg was within his diocese. Albert was heavily in debt from bribing the Roman Curia to hold two dioceses. He hoped to use proceeds from selling indulgences to pay off his debts. Albert and the preachers involved in the sale were displeased by Luther’s criticism and sent it to Rome.

Papal authorities could have dismissed the entire matter if it were not for Luther’s skill in using modern media. Modern, in the sense of the sixteenth century, refers to the printing press. Luther published his arguments, which quickly caught the attention of like-minded individuals. What began as a scholarly critique of a specific Church practice escalated into a dispute over doctrine and papal authority. While the conflict focused on Luther and Wittenberg, reformist influences spread across the Empire. The territorial princes in the south remained mainly Catholic, but many cities, such as Kiechel’s hometown of Ulm, chose to become Protestant.

The beginning of the Protestant Reformation coincided with the reign of Charles V (1500–1558) of the Habsburg Dynasty. Charles ruled over a vast empire that included large parts of Europe and the Spanish colonies in America. He spent much of his time as ruler fighting the new Protestant ideas. Maintaining religious unity was crucial for such a large empire.

Charles V summoned Martin Luther to the Diet of Worms in 1521 and assured him safe conduct. The Imperial Diet was a deliberative assembly of the Imperial Estates of the Holy Roman Empire that met regularly. The locations of the Diets moved between cities until the seventeenth century.

Charles V, 1548

In Worms, Luther was asked to either renounce or confirm his criticisms. He reaffirmed his views and was therefore considered a heretic and declared an outlaw. Because Charles had guaranteed his safety, Luther was allowed time to leave the city.

Much to Charles’ frustration, this sentence had little effect. Luther’s ideas had already spread and gained the support of some influential regional princes of the Empire. Notably, Frederick III, Prince-Elector of Saxony, helped Luther avoid both papal and imperial authorities, hiding him at Wartburg Castle near Eisenach in modern Thuringia.

Frederick III, 1533

Frederick died in 1525, and his successor, his brother John (John the Steadfast, 1468–1532), established the Protestant faith as the official religion of the Duchy of Saxony in 1527. Other regions, especially in the north of the Empire, followed suit, and reformers such as Martin Bucer, Huldrych Zwingli, and John Calvin became active in cities in southern Germany and Switzerland.

At the Diet of Augsburg in 1530, the “Confessio Augustana” (Augsburg Confession) was presented to the Emperor. The Diet was seen as an attempt at reconciliation amid the Ottoman Empire’s military advances. Under Sultan Suleiman the Magnificent, the Ottomans had laid siege to Vienna the previous year (1529).

Charles had asked the Protestant princes and free cities to explain their religious beliefs. The “Confessio Augustana” consisted of twenty-eight articles that represented the main principles of the Protestant faith. However, the Diet became confrontational, and Charles, along with the papal legates, presented a response to refute the “Confessio” and demanded a return to the Catholic Church.

In response, and as a defence against a possible attack by Charles, the Protestant princes formed the Schmalkaldic League in 1531. The League grew into a powerful bloc within the Empire. Yet, like many alliances of influential people with differing political ambitions, it was troubled by internal struggles and disagreements about its aims and purposes.

In 1546, it finally came to a military confrontation. Charles decided to unite the Empire under his rule by force. The members of the Schmalkaldic League chose to wage a pre-emptive war due to Charles’s significantly larger resources (Schmalkaldic War, 1546/1547). However, the League was defeated, and Charles captured many of its leading figures.

One of the captured princes was John Frederick, Elector of Saxony and nephew of Frederick III. Charles initially sentenced him to death, but subsequent negotiations changed the sentence to imprisonment. These talks led to the Capitulation of Wittenberg (1547). John Frederick was forced to surrender his title of Elector of Saxony and much of his territory. The title and land were transferred to Maurice of Saxony (1521-1553), who belonged to the Albertine line of the House of Wettin. Maurice was a Protestant, but during the Schmalkaldic War, he remained loyal to Charles.

The victorious Charles, now at the height of his power, ordered the Protestant princes to reintegrate into the Catholic Church through the Augsburg Interim, an imperial decree issued in 1548. The Augsburg Interim was a compromise that included some concessions to the Protestants. However, most Catholic princes in the Empire were now reluctant to agree. They opposed the Interim, fearing it might introduce Protestant practices into their territories. As a result, Charles had to agree that the Interim would only be enforced in Protestant lands. This decision sparked renewed resistance among the Protestant princes.

The new Elector of Saxony, Maurice, played a crucial role. He had been shunned within the Protestant community after supporting Charles in the Schmalkaldic War. With many princes uneasy about the Augsburg Interim, Maurice saw his opportunity and led a rebellion against the Emperor. The uprising took Charles by surprise and forced him to retreat. Attempts to reconcile both sides in the following years proved unsuccessful.

In 1555, Charles’ brother Ferdinand negotiated the Peace of Augsburg. The treaty temporarily ended the religious conflict. Protestantism was effectively recognised as a legal confession within the Empire. The princes of the German territories were allowed to decide on the religion of their domains.

However, the religious division persisted after the Peace of Augsburg. Calvinists and other Protestant groups were excluded from the treaty. The Catholic Church aimed to reclaim lost territories through the Counter-Reformation, while Protestant adherents sought to establish a foothold in southern German regions. At the time of Samuel Kiechel’s journey, the already decentralised and fragmented Empire was a patchwork of regions and cities with diverse religious beliefs, some Protestant and some Catholic. Ultimately, the Peace of Augsburg proved to be merely a temporary respite. Confessional tensions would flare up again, culminating in the Thirty Years’ War (1618-1648), one of the most destructive conflicts of the era.

Religion and Travelling

Questions of faith and religion played a role in Samuel Kiechel’s journey. Our traveller was not a pilgrim, but he visited the holy sites in Palestine. Kiechel did not openly share his religious beliefs but did mention when he disagreed with different practices. Possibly because of the lingering tensions between the Catholic Church and the Protestant faith at home, Kiechel seemed more tolerant towards Muslims than Catholics. What he observed of Muslim religious practice in the Ottoman Empire and Egypt was approached with the curiosity of a tourist, whereas Catholic practice appeared dull and outdated to him.

Samuel Kiechel was also aware of the dangers posed by religious tensions. His first journey abroad was into the conflict zone of the Dutch War of Independence (or Eighty Years’ War, 1568–1648) between the Protestant northern Dutch provinces and the Catholic Kingdom of Spain. Our traveller visited both the independent provinces and the Spanish Netherlands.

In Italy, Kiechel was careful not to arouse suspicion of the Inquisition. While in the Holy Land, he joined a group of Catholic pilgrims and pretended to be one of them. However, his companions grew suspicious, and tensions within the group escalated. Eventually, they threatened to report him to the Inquisition once they returned to Venice.

Nevertheless, while there was some danger in holding beliefs that did not conform to the dominant faiths of the countries he visited, Kiechel rarely stayed long enough for suspicion to deepen. Additionally, strange behaviour could often be seen as cultural differences.

Illustrations & References

All images are in order of appearance with links to sources on external websites:

- Wittenberg, in: Reisealbum des Pfalzgrafen Ottoheinrich 1536/37; Wikimedia Commons.

- Avercamp, Hendrick, View of a Country House with Sowers in the Field, c. 1610 – c. 1615; Rijksmuseum Amsterdam.

- Ortelius, Abraham, Theater of the World, Antwerp 1587, fol. 50v; Library of Congress.

- Wittenberg, in: Braun/Hogenberg, Civitates Orbis Terrarum (1), Cologne 1593, fol. 27v; Heidelberg University.

- Aldegrever, Heinrich, Portret van Martin Luther, 1540; Rijksmuseum Amsterdam.

- Tiziano Vecellio, gen. Tizian, Bildnis Kaiser Karls V. im Lehnstuhl, 1548, Bayerische Staatsgemäldesammlungen – Alte Pinakothek München.

- Lucas Cranach the Elder, Friedrich III (1463–1525), the Wise, Elector of Saxony, 1533; Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York.

- Saftleven, Herman: Een zittende en drie staande mannen, 1619 – 1685; Rijksmuseum Amsterdam.

- Die Reisen des Samuel Kiechel aus drei Handschriften, K. D. Haszler (ed.), Stuttgart 1866, p. 5; Bayerische Staatsbibliothek. ↩︎

- Pabel, Angelika, Pleticha-Geuder, Eva, Schmid, Anne, Schmidt, Hans-Günther (eds.): Reise, Rast und Augenblick. Mitteleuropäische Stadtansichten aus dem 16. Jahrhundert, Ausstellungsführer, Dettelbach 2002. ↩︎