“Dresden is in the land of Meissen, and the Elector of Saxony has his residence there. The city is small and heavily fortified. It is a pleasant place with beautiful straight and wide streets. The houses of Dresden are built of stone.”1

From Prague to Dresden

7 June – 9 June 1585

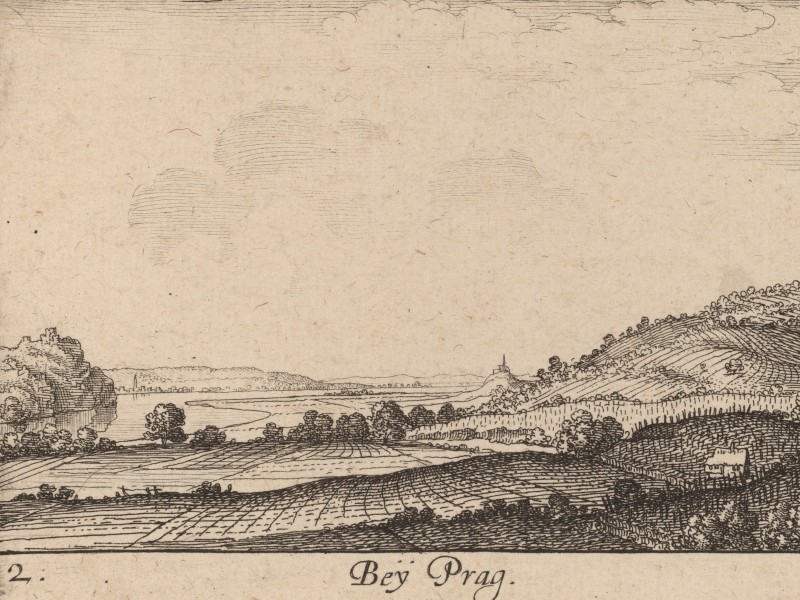

Watching the world pass by from a post-coach window seems quite similar to modern travel. After crossing the mountain range of the Bohemian Forest on foot, a carriage ride to Dresden must have sounded more comfortable to Samuel Kiechel, despite the limitations that such vehicles had in the sixteenth century. The destination, Dresden, was another city worth visiting then, just as it is now.

Leaving Prague

Samuel Kiechel left Prague in the afternoon of 7 June. He had paid for passage in a carriage to Dresden. With him were two more passengers in the vehicle — a Dutch painter and a chef. Kiechel does not mention it explicitly, but he used a postal carriage for this part of his journey. Our traveller would have noted if he had been invited to travel in a private coach.

The postal carriage with our traveller drove from Prague to Budin (Budyně nad Ohří), where he spent the night. The following morning, it continued and arrived in the small town of Aussig (Usti nad Labem) at lunchtime.

Samuel noted that Aussig, situated on the river Elbe (Czech: Labe), was surrounded by a countryside that produced excellent wine. A hill near the river was home to a renowned vineyard where the best wine in the Kingdom of Bohemia was cultivated. This vineyard supplied the court of the Emperor in Prague.

The area along the Elbe was renowned for its vineyards. In this map segment, the town of Leutmeritz (Litoměřice) on the other side of the river from Budin and Aussig is described as “hic colles sunt vineis consiti” — where hills are covered with vineyards.

The carriage with Kiechel and the other two passengers stopped for the night in Peterswald (Petrovice), a village at the border between the Kingdom of Bohemia and the Duchy of Saxony.

Across the Ore Mountains

The Ore Mountains (Germ.: Erzgebirge) are a mountain range on the border between Saxony (Germany) and Bohemia (Czech Republic). As the name suggests, the mountains were rich in ore. In particular, tin, silver, copper and iron were mined in the region. The river Elbe had cut a path through the Ore Mountains, and various roads led across their passes.

Samuel Kiechel’s journey from Prague to Dresden followed one of the major transit routes through the mountains — the “Kulmer Steig”. Kulm (Chlumec) is a town on the Bohemian side of the Mountains, and ‘Steig’ is an old German word for a narrow and steep path. However, the name did not mark a single road but various routes across the eastern part of the Ore Mountains.

Daniel Wintzenberger’s “Reyse Büchlein” from 1578 describes the same route Samuel Kiechel took. Wintzenberger mentions the towns of Welbern (Velvary), Budin (Budyně nad Ohří), Labositz (Lovosice), Außig (Usti nad Labem), Peterswald (Petrovice) and Pirna along this route.2

The road from Usti nad Labem to Petrovice led through the Nollendorfer Pass (Nakléřov Pass) and was the easternmost crossing of the “Kulmer Steig” over the Ore Mountains.

The distance between Petrovice and Dresden was five miles. Kiechel’s carriage covered it in half a day and arrived in the city at lunchtime.

Mapping Saxony

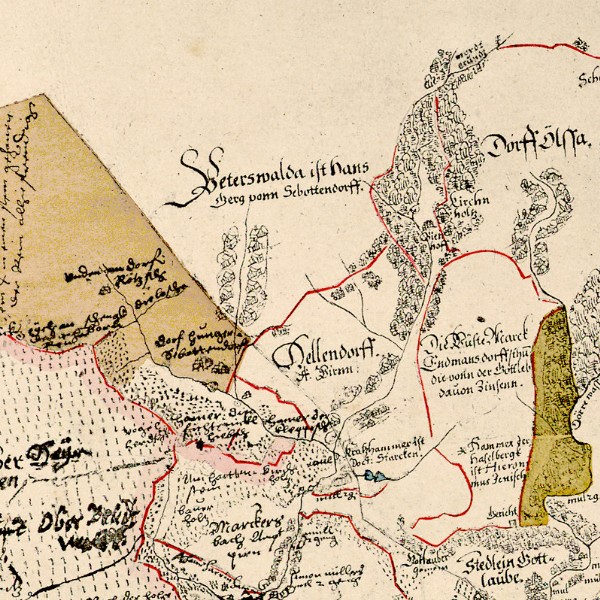

A set of regional maps from the late sixteenth and early seventeenth centuries shows the countryside of Saxony. Inspired by the ”Bairische Landtafeln”, the Elector of Saxony, August I (1526 – 1586), commissioned the surveyor Matthias Oeder in 1586 to make a similar set of maps of Saxony. Oeder’s successors finished the maps in the 1630s. Unlike their Bavarian counterparts, the maps of Saxony were never printed and published.3

Ore Mountains around Petrovice on the Oeder-Map

Mapmaking in the Sixteenth Century

Compared to previous centuries, mapmaking had evolved rapidly in the sixteenth century. New surveying techniques and better instruments to measure distances and angles have been developed. The Dutch physician, mathematician and astronomer Gemma Frisius published “Libellus de locorum describendorum ratione” in 1533 — a book on the method of triangulation. Geographic accuracy grew in importance and supplanted the religious motifs of medieval cartography. With the help of the printing press, local and regional maps began to be produced and published in large numbers.4

However, despite these developments, no global and very few regional or local maps were the products of large-scale surveys. In contrast to measuring fields or local borders, surveying a large area requires a systematic approach. The available instruments to measure distances were still inaccurate, the mathematical calculations for the distances and angles were complicated, and the cost of a large-scale survey was far too high for the individual mapmaker or surveyor.

The Cassini Map of the Kingdom of France was the first map of a whole country made by triangulation and is a good example of the efforts and expenses involved. King Louis XIV ordered the map and financed the work. Initial surveys began in 1669, but work was interrupted between 1683 and 1700 due to the death of Jean-Baptiste Colbert. Colbert was the First Minister of State under Louis and a major supporter of the endeavour. Louis XIV ordered the work to continue in 1700. The first map was published in 1744. It showed only the borders of France and the triangles used to measure and survey the kingdom. Work continued, and the map was divided into regional and local segments to allow for a larger scale and more detail (landscape, settlements, fields). The final sheets of the Cassini map were published in 1818.

The Oeder-Map

Matthias Oeder surveyed and measured parts of Saxony. However, despite the application of modern techniques, there was no systematic approach to it. The maps of Saxony are an amalgamation of many local surveys without an overarching framework. Despite these issues, the maps were the most accurate depictions of the region at the time.

The survey maps of Saxony are oriented towards the south. They show the landscape along the river Elbe from the Ore Mountains to Dresden, Meissen and Leipzig as a mixture of villages, small towns, fields and forests. In addition, the maps contain extensive written information about the various places. For every settlement, fortification and economic structure (e.g. mills), as well as forests and meadows, the owner is mentioned by name. Peterswald belonged to Hans Georg von Sebottendorf (on the map ‘Hans Gerg vonn Sebottendorff’).

Peterswald/Petrovice (“Peterswalda ist Hans Gerg vonn Sebottendorff”)

The villages in the higher reaches of the Ore Mountains are presented as elongated and stretched out. These places were along the banks of one of the many small streams of the region. The streams had cut deep valleys into the landscape, and the mountains on both sides hemmed in the settlements.

Gottleuba, Gersdorf and “Haus Giessenstein”

A few roads are visible on the maps, but because the mapmakers used no uniform set of symbols, they are difficult to distinguish from the rivers.

Samuel Kiechel’s route led from Peterswald through Gottleuba, Gersdorf and Ottendorf to Pirna on the Elbe. On the maps, a thin line connects all those places.

According to the maps, Kiechel’s carriage travelled past hammer mills and fortifications. The mills were part of the mining industry that processed the ore from the mountains. Fortifications like “Haus Giessenstein” on the river Gottleuba had been built to safeguard this transit route.

From Pirna, the road followed the Elbe to Dresden. In contrast to the many details on the survey maps, Dresden is only depicted by a circular fortification and a bridge across the Elbe. The mapmakers did not even write the name on the map.

Dresden on the Oeder-Map

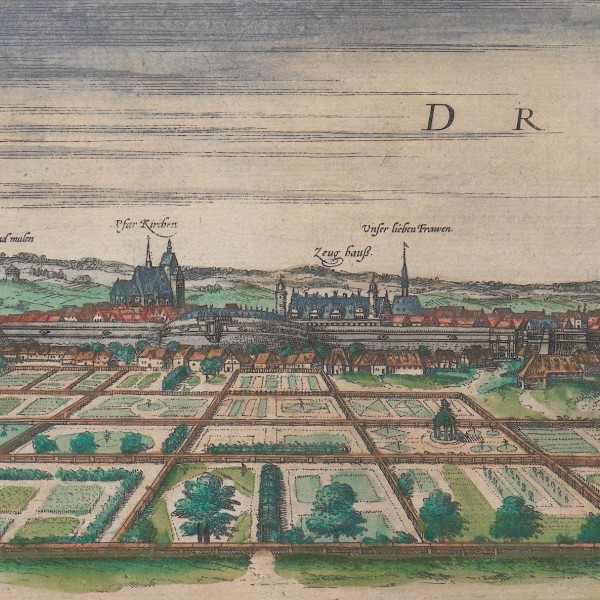

Visiting Early Modern Dresden

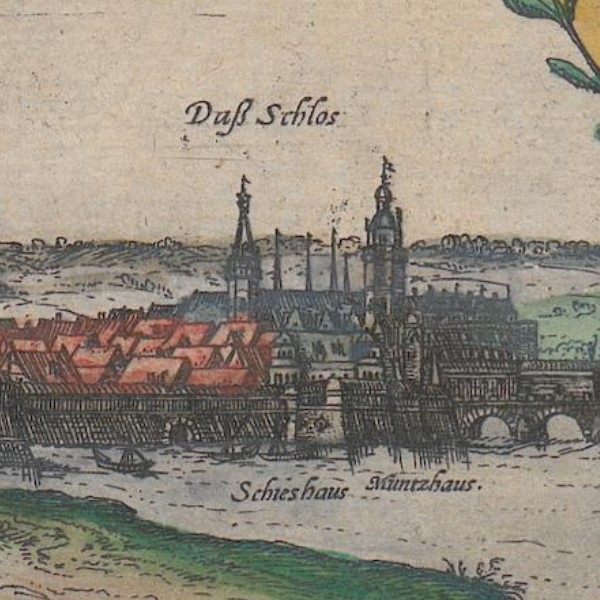

Samuel Kiechel’s first impression of Dresden could not have been much different to this view of the city. The view presents Dresden from the south — the direction our traveller had arrived from. Small fields, gardens and meadows surround the city on the river Elbe. A long stone bridge leads across the river and connects the two parts of Dresden. The settlement on the western bank of the river is the larger of the two and is fortified by a wall. But the fortifications could no longer contain the growing city, and houses had been built outside the wall. Dresden’s two major churches, the armoury and the palace of the Elector of Saxony stand out and dominate the skyline.

Between 1546 and 1591, the walls of Dresden were modernised and in part rebuilt. In the image, they look sturdy and are in the style of the early modern period. At least three bulwarks are visible, with intermittent sections of curtain wall between them. The increased use of gunpowder made the old, medieval fortifications of cities and castles obsolete. High walls were no longer a sufficient protection. Lower, sturdier walls with protruding bulwarks provided the defenders with better lines of fire and became the new architectural norm. For modern visitors to the city, Brühl’s Terrace on the bank of the river Elbe had once been a part of early modern Dresden’s fortifications.

The view of Dresden confirms some of Samuel Kiechel’s observations. Our traveller wrote that the city was small and heavily fortified. The Elbe flowed through it, and a delicate stone bridge led across the river.

The description of Dresden in Kichel’s journal is just one paragraph long. As usual, our traveller started by identifying the territory and ruler to which the city belonged. Dresden was in the land of Meissen — an administrative district of the Duchy of Saxony — and it was the residence of the Elector of Saxony. The palace of the Elector is seen close to the river in the centre of the image (“Daß Schlos”).

Entering Dresden, our traveller observed that its houses were well-built and made of stone. Beautiful, straight and broad streets led through the city. At the market square, Kiechel took up his accommodation in the inn “Zum Goldenen Ring” (Golden Ring).

The market square our traveller mentioned is today’s Altmarkt (Old Market Square). At its southwestern corner stood the inn where Kiechel stayed.

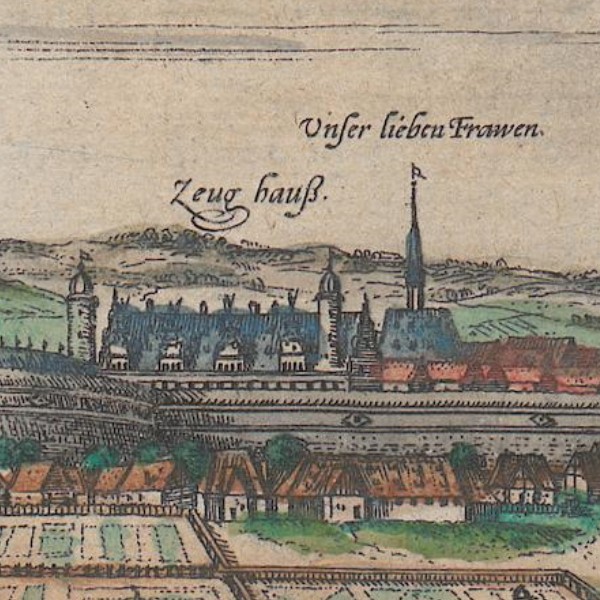

Samuel Kiechel visited the armoury (“Zeug Hauß”) of Dresden. He was impressed and described it as among Germany’s most beautiful half-timbered buildings and a joy to look at. The armoury was also well stocked.

In the view, the roof of the armoury is to the left of the Frauenkirche (“Unser lieben Frawen”, Church of Our Lady). The Frauenkirche is a previous version of the rebuilt, famous, baroque, eighteenth-century Church that is today a major attraction of Dresden. The armoury was modified and converted into the Albertinum (Museum of Modern Art) in the late nineteenth century.

The armoury of Dresden is mentioned in the text accompanying the view in the “Civitates Orbis Terrarum”. In contrast to Kiechel’s observations, the text does not describe the building itself but rather its contents: The armoury contains many different types of armour, arquebuses, shot, powder, and other things used for war. The many heavy guns are of such beauty and size that the author of the text refused to write more about them, as he suspected people would not believe him.

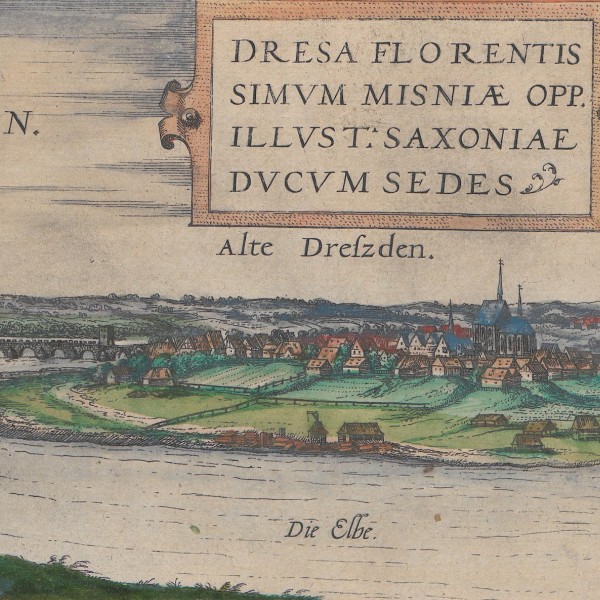

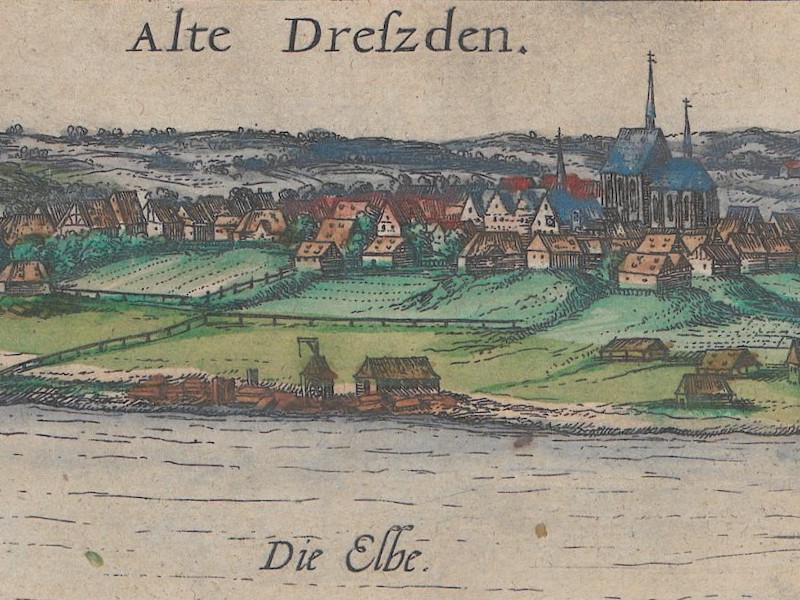

The Bridge and Altendresden

Kiechel mentioned the bridge across the Elbe. He wrote that it was beautiful and delicate, connecting the New Town on the western bank of the river with the Old Town on the eastern side.

A print from 1585 provides a closer look at the bridge and the palace.

This image was made from the river’s eastern bank. It is almost identical to the point of view of a later and more famous painting of Dresden. The Italian artist Bernardo Bellotto painted it in 1748 (Dresden From the Right Bank of the Elbe Below the Augustus Bridge).

What our traveller identified as the Old Town and what is marked in the view as “Alte Dreszden” is today part of Dresden-Neustadt (New City). The name ‘Neustadt’ was given to the area in the eighteenth century.

In the Middle Ages, two separate settlements were founded — one on each side of the river. The settlement on the western bank of the river developed into the city of Dresden, with all its sights and historic buildings still visible today. The settlement on the Elbe’s eastern bank remained a village called Altendresden. In 1549, Altendresden became part of Dresden, but the name remained in use throughout the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries.

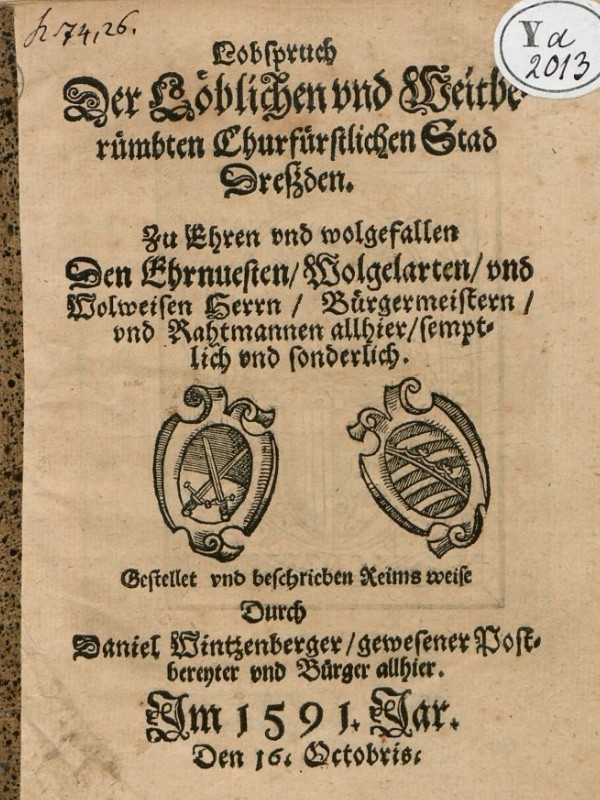

A Panegyric of Early Modern Dresden

Besides two Itineraria, the messenger and post rider Daniel Wintzenberger had written a short panegyric of his hometown.5 (A panegyric is a speech or text praising someone or something.) This text is in the form of a poem.

Wintzenberger writes: Dresden has four inns at the market square — the Golden Lion, Golden Sword, Golden Ring and the Morningstar. A fifth inn is on a side road (Seegasse).

The city has two main churches, the Church of the Holy Cross (Kreuzkirche) and the Church of Our Lady (Frauenkirche). The Church of the Holy Cross is a graceful building with a beautiful altar and stone font. The tower of the Church has two walkways at the top. From there, guards watch for fire or other dangers and warn the city’s inhabitants. The roof of the tower is made of copper and painted green. On top of the church tower is a golden cross.

The houses in Dresden are well-built and beautiful. The council enforces a strict regimen to keep the city clean. People have to take care of the street in front of their houses. Refuse has to be removed quickly, or the person responsible for that part of the street is fined.

On his journey, Samuel Kiechel often showed interest in the price and availability of food and drink in the places he visited. The following part of Wintzenberger’s panegyric would likely have caught the attention of our traveller:

Many butchers live in Dresden. They import animals from Poland, Bohemia, and Silesia, as well as from the surrounding land of Meissen. Meat is readily available in the city and sold at a reasonable price. The bakeries of Dresden sell bread for a Groschen, half a Groschen, three Pfennig or one Pfennig.

As for drinks, wine from Greece, Spain, Franconia and the Rhineland is available. But there is also good local wine from the hills along the Elbe and Bohemia. Beer is imported from Freiberg, Torgau, Belgern and other places. But the beer produced in Dresden is also of high quality.

The final part of Wintzenberger’s panegyric is about the bridge across the Elbe. He writes that the bridge’s construction began in 1119 and took thirty years. The bridge was 900 cubits long ( cubit = the distance from the fingertips to the elbow) and had twenty-one arches. Later, the bridge was shortened by three arches.

Illustrations & References

All images are in order of appearance with links to sources on external websites:

- van Cleve, Hendrick, Dresda, 1585; Rijksmuseum Amsterdam.

- Hollar, Wenceslaus, Title Page, Amoenissimae Aliquot Locorum in Diversis Provinciis Iacientiu Effigies, 1635; National Gallery of Arts, Washington, DC.

- Hollar, Wenceslaus, Bey Prag, 1635; National Gallery of Art, Washington, DC.

- Ortelius, Abraham, Theater of the World, Antwerp 1587, fol. 53v; Library of Congress.

- van Valckenborch, Frederik, Gezicht op een dal met een dorp en een bergbeekje, 1598-99; Rijksmuseum Amsterdam.

- Die erste Landesvermessung des Kurstaates Sachsen Auf Befehl Des Kurfürsten Christian I. ausgeführt von Matthias Oeder (1586-1607). Zum 800Jährigen Regierungs-Jubiläum Des Hauses Wettin, Dresden 1889, map 3.

- Ibid, map 9.

- Dresden, in: Braun, Georg, Hogenberg, Frans, Civitates Orbis Terrarum (1), Cologne 1593, fol. 28v; Heidelberg University.

- Wintzenberger, Daniel, Lobspruch der Loeblichen vnd Weitberuembten Churfuerstlichen Stad Dreßden, Dresden 1591; University Halle-Wittenberg.

- Die Reisen des Samuel Kiechel aus drei Handschriften, K. D. Haszler (ed.), Stuttgart 1866, p. 4; Bayerische Staatsbibliothek. ↩︎

- Wintzenberger, Daniel, Ein naw Reyse Büchlein von der Stad Dreßden aus durch gantz Deudschlandt in die andern anstossenden Königreichen und umbligenden Lendern, Dresden 1578. ↩︎

- Die erste Landesvermessung des Kurstaates Sachsen Auf Befehl Des Kurfürsten Christian I. ausgeführt von Matthias Oeder (1586-1607). Zum 800Jährigen Regierungs-Jubiläum Des Hauses Wettin, Dresden 1889. The University of Göttingen provides a digital version: http://resolver.sub.uni-goettingen.de/purl?PPN543440540 ↩︎

- Lindgren, Uta, Land Surveys, Instruments, and Practitioners in the Renaissance, in: Woodward, David (ed.), The History of Cartography, Vol. 3 (Pt. 1): Cartography in the European Renaissance, Chicago 2007, pp. 477-508. ↩︎

- Wintzenberger, Daniel, Lobspruch der Loeblichen vnd Weitberuembten Churfuerstlichen Stad Dreßden, Dresden 1591. ↩︎