“Antwerp is the capital of Brabant and is under the rule of King Philip of Spain. Before the war, no other city in Europe or the world surpassed it in trade.”1

From Ghent to Antwerp

01 December – 10 December 1585

A notable difference between travelling in the sixteenth century and today was the lack of guidance and safeguards to steer travellers away from dangerous areas and to provide safe alternative routes. Travellers had to look after themselves, ask around to learn about the road ahead, and find trustworthy guides and companions.

In the late sixteenth century, the Low Countries (comprising today’s Netherlands, Belgium, and Luxembourg) were embroiled in the Eighty Years’ War (1568-1648) between the Dutch Republic and the Kingdom of Spain. The options for safe alternatives to avoid the area were limited. As our traveller, Samuel Kiechel, knew, taking a ship back to Germany put him in danger from privateers prowling the Channel and North Sea Coast. It also made him dependent on the wind and weather, with winter approaching. Circumventing the war-torn area to the south would have meant a lengthy detour. While staying in Calais, Kiechel had considered this option due to the danger on the road to Antwerp, but could not find companions.

Our traveller was forced to cross the war zone to reach his destination and found himself in a city that had recently been under siege. Antwerp had long been the economic and cultural heart of the Low Countries, making it an attractive destination for curious visitors. However, it had been besieged by a Spanish army and surrendered just months before our traveller arrived. Kiechel was fully aware of the blockade and had undoubtedly heard of the Spanish victory. Nonetheless, it did not deter him; lacking other options, he visited the city, as it was an essential stop on the way to Cologne.

In Ghent

Samuel Kiechel and his two companions arrived in Ghent on the last day of November. Our traveller described the city as the capital of Flanders and noted that it was regarded as the largest city in both Upper and Lower Germany. Furthermore, he observed that Ghent was under the rule of King Philip (Philip II of Spain, 1527-1598). The father of Philip, Charles V (Emperor Charles V, 1500-1558), was born in that city. On the northeastern side of Ghent, towards Antwerp, stood a large fortress. The fortress was garrisoned by Spanish soldiers and surrounded by a wide moat.

Kiechel’s comment that Ghent was a German city stemmed from the region’s historical ties to the Holy Roman Empire and the dynastic links of the ruling Habsburg family. The Habsburgs gained control of the Netherlands when Maximilian of Austria (later Emperor Maximilian I, 1459-1519) married Mary of Burgundy in 1477. After her death in 1482, he inherited the Burgundian Netherlands. Maximilian and Mary’s son, Philip (1478-1506), married Joanna of Castile in 1498, thereby establishing the Habsburg dynasty in Spain. Philip died in 1506; his son, Charles, inherited all Habsburg territories. Charles was born in Ghent’s Prinsenhof in 1500. As Kiechel noted, Charles’ son was Philip II of Spain.

Ghent, 1545

Maps of Ghent are included in the “Civitates Orbis Terrarum” and Jacob van Deventer’s collection of sketch maps. As with Saint-Omer, Lille and Kortrijk, the publishers of the “Civitates” had used van Deventer’s map and adjusted it to fit. However, this time, much of the surrounding landscape was not cropped. Van Deventer’s map of Ghent is oriented towards the south, while the “Civitates” presents the city from the west. The notable difference between the two maps is the extensive legend with 103 entries in the view published in the “Civitates”.

Ghent, 1572

In both maps, Ghent is a large, sprawling city with numerous canals crossing through it. There are many windmills surrounding the city in all directions. The fortress, Kiechel mentioned, is easily recognisable. However, it is not Gravensteen Castle, the medieval stronghold that was the seat of the Counts of Flanders and is now one of Ghent’s main tourist sights. Gravensteen had fallen into decline in the sixteenth century. It is marked as no. 31 in the centre of the lower half of the map in the “Civitates”, near where four large canals converge.

The large fortress depicted on the map was constructed around 1540 under the orders of Charles V, following the citizens’ rebellion against him in the Revolt of Ghent (1539-1540). Saint Bavo’s Abbey once stood on this site, but it was demolished to make way for the fortress. Its purpose was not to defend the city but to control it. As Kiechel noted, Spanish soldiers garrisoned the fortress.

The Road to Antwerp

Samuel Kiechel and his two companions spent the night in Ghent. At the inn, a mercenary approached the group and asked to join them. The group agreed, and they left the following morning (1 December).

However, after five miles, the mercenary began to fall behind and eventually stopped in a village. Kiechel’s companions, who had been with him since London, distrusted the mercenary and suspected him of being a brigand. Kiechel agreed, noting that it was only the lack of accomplices that had prevented the mercenary from robbing them. When the man had fallen far enough behind, Samuel and his companions spurred on their horses and rode off at speed.

The travellers arrived in the village of Haasdonk in the evening. They put their horses into the stable and were about to take off their boots when the innkeeper rushed in and announced that her best horse had been stolen. The horse was valued at 60 Brabant guilders. Upon hearing this, the messenger was so worried that he spent the night in the stable. Kiechel and his other companion did not have a restful night either. Their room had no lock and was on the ground floor facing the road. There was no bed in the room, so the two men had to sleep on benches.

The travellers left the village before daybreak the following morning and rode until they reached the Scheldt River half a mile from Antwerp. They left their horses behind and continued the journey on a small boat. The boat did not travel along the river itself but across flooded land where meadows had once been. They returned to the Scheldt just opposite Antwerp and only had to cross the river to reach the city.

The Siege of Antwerp

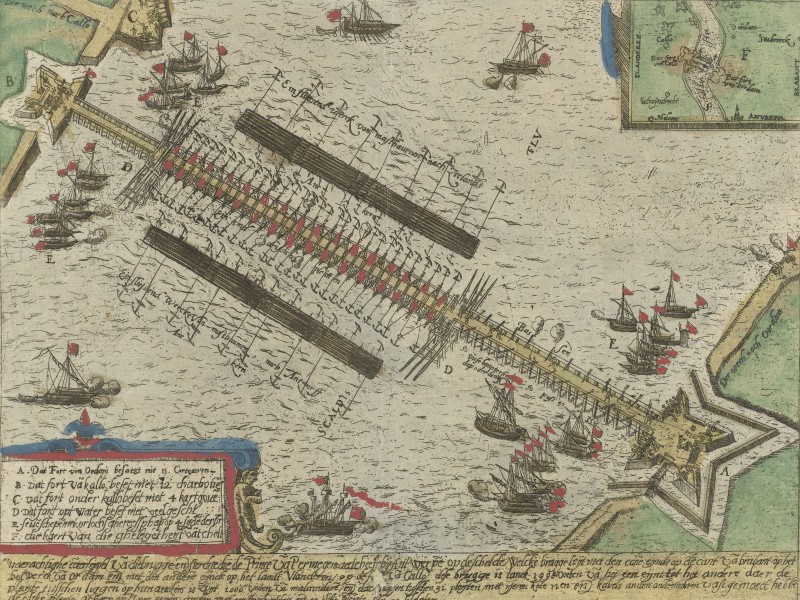

The submerged land resulted from the siege of Antwerp. Antwerp had joined the Dutch rebellion against Spain in 1579 (Union of Utrecht), after mutinous Spanish soldiers had sacked it three years earlier. The city was the economic and cultural centre of the Low Countries and one of the leading trade hubs in Western Europe, with the Scheldt River serving as its gateway to international trade routes. During the ongoing conflict, Antwerp was besieged in July 1584 by a Spanish army led by Alessandro Farnese, Duke of Parma (1545-1592).

In response to the siege, the defenders employed a typical Dutch tactic suited to the landscape. They opened the dykes and flooded the surrounding countryside to stop or at least impede advancing armies. Frans Hogenberg, the engraver behind the “Civitates Orbis Terrarum” and a former resident of Antwerp, created a print of this event in the same year. The image illustrates the aftermath of the action, with the area around Antwerp largely submerged.

The submerged land around Antwerp during the siege

However, the Spanish managed to maintain their siege, and by 17 August 1585, Antwerp was compelled to surrender. Attempts to relieve the city with the aid of English troops arrived too late. Samuel Kiechel had witnessed the arrival of an English army while he was in Vlissingen three months prior.

Antwerp after the Siege

Despite Antwerp having just been besieged for a year and now being under Spanish occupation, Samuel Kiechel mentioned no increased security measures or any difficulties when entering, staying in or departing the city.

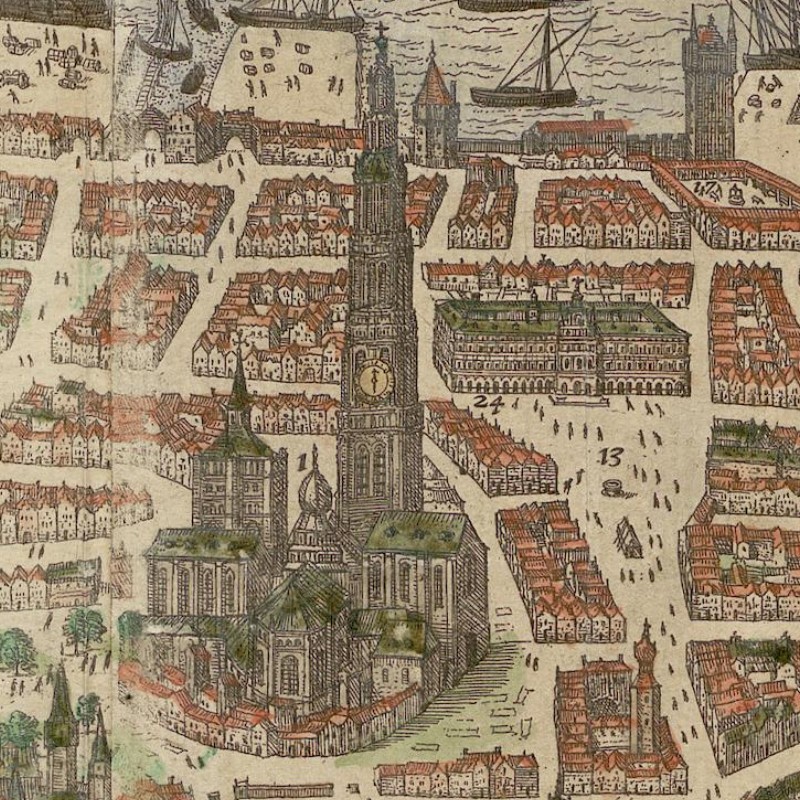

Antwerp, 1572

Our traveller wrote that Antwerp was the capital of the province of Brabant and was under Spanish rule. Before the war, the volume of trade in Antwerp was greater than in any other city in Europe or the world. The trade was so lucrative due to the city’s location and its proximity to the sea. Multiple canals led from the river Scheldt into the city.

In Antwerp, our traveller saw a beautiful high tower. The tower had a clock, and its bells played a verse from the psalter before it rang the hour. Samuel found the bells charming to listen to. Around the market in Antwerp, he saw many well-built and tall houses. The town hall was also a beautiful building.

The tower was the belfry of the Cathedral of Our Lady.

Cathedral of Our Lady and the town hall (located on the right behind the cathedral)

The Harbour of Antwerp

Kiechel wrote: In the harbour, each nation had a designated place to moor its ships. The English and Scottish ships had their separate quays, as did the ships from Spain, Portugal, France, Italy and other regions. Each foreign trading nation had its own house. These houses were all well-constructed, decorated and large. Two sides of each house faced the land, while the other two faced the water’s edge, allowing large ships to moor at its gateway. No other buildings had been constructed around them.

The buildings Kiechel mentioned were warehouses used for storing trade goods that the ships loaded or unloaded.

Antwerp, 1598

Two bird’s-eye views of Antwerp are found in the “Civitates Orbis Terrarum”. Both views are pretty similar. The first image depicts the city from the south, and the second from the east.

The river Scheldt and the harbour facilities of Antwerp are visible in both maps. The harbour is divided into several quays. In both views, the quays are busy areas with many vessels anchored and goods ready for transportation into the warehouses.

Antwerp harbour

The Spanish Occupation

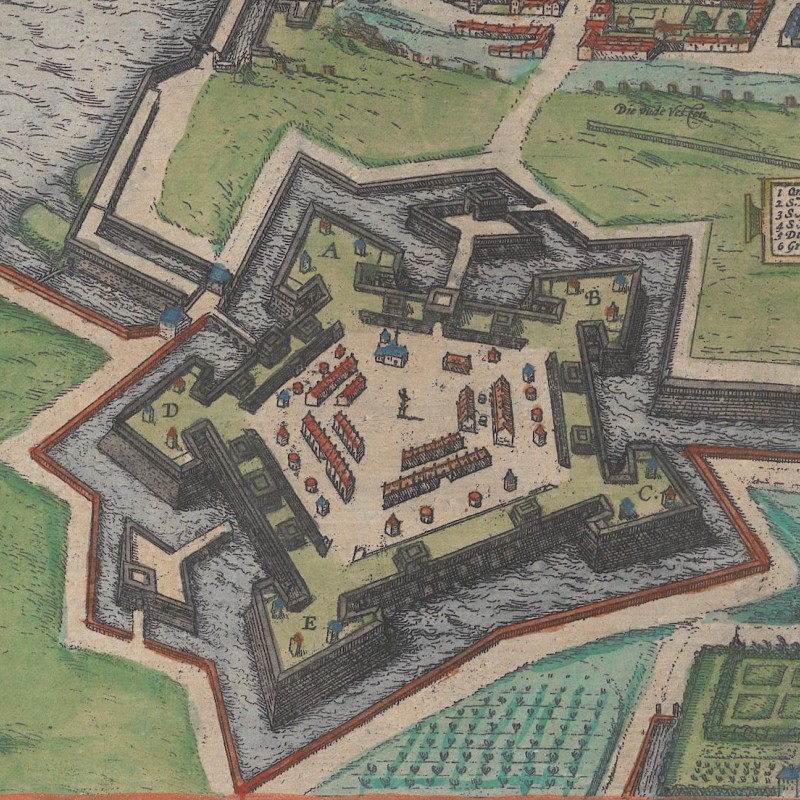

The fortress of Antwerp

Furthermore, Kiechel wrote: Antwerp was surrounded by walls, and at one end of the city was a fortress. The fortress walls had been demolished before the siege. After the fall of Antwerp, the Duke of Parma, commander of the Spanish army and governor of the Spanish Netherlands, ordered the walls rebuilt to their previous strength. Spanish troops now garrisoned the fortress, while the soldiers in the city and at the gates were Germans and Walloons. The Spanish removed all the mounted guns from Antwerp and brought them to the fortress. Kiechel went to have a look and wrote that he saw many beautiful cannons there.

After the capitulation, Alessandro Farnese placed experienced Spanish soldiers in the city. Compared to the siege of 1576, the Spanish did not sack Antwerp, and discipline among the soldiers was enforced to prevent a similar massacre. Farnese gave Antwerp’s Protestant population the choice to revert to Catholicism or leave the city. Those who would not convert had four years to settle their affairs. A large proportion of Antwerp’s Protestants were merchants and craftsmen. Many of them relocated to the northern provinces, helping Amsterdam to rise as an economic and cultural centre during the Dutch Golden Age in the seventeenth century.

The fortress is clearly recognisable in both bird’s-eye views of Antwerp in the “Civitates”. It is situated on the southern edge of the city and is surrounded by a moat.

Bridge constructed over the Scheldt during the siege, 1585

Samuel Kiechel also mentioned the bridge that the Duke of Parma ordered to be built to block the Scheldt River and cut Antwerp off from access to the sea during the siege. The bridge was made of wood and crossed the river downstream of Antwerp. Several attempts by the Dutch defenders to destroy it failed. Kiechel noted that the bridge had been removed shortly before his visit to the city.

News and Communication

Samuel Kiechel also noted that it was common for children of Antwerp’s citizens to speak three or four different languages, such as French, Italian or Spanish, in addition to their native Dutch. These children went to the ‘böers’ (stock exchange) where merchants gathered. They would seek out large groups of merchants from various countries and listen to their conversations to learn about events elsewhere.

This little anecdote is a good example of how news was transmitted in the sixteenth century. Word of mouth remained the primary way of passing on knowledge. While there were letters, embassies, messengers and, thanks to the printing press, leaflets, pamphlets and early newspapers, they were only accessible to those who could read and write. Most people still relied on oral communication to share news, with all the associated risks, not unlike the distortions in the game ‘Chinese whispers’.

Visiting an Occupied City

For a city that had just endured a year under siege and surrendered due to famine, Samuel Kiechel did not mention any signs of destitution among the population or destruction within the city. Instead, he noted that there were ways to entertain travellers. Antwerp had schools for fencing and dancing, as well as opportunities to learn musical instruments. Kiechel also observed that the women of Brabant were more modestly dressed than those in Holland, Frisia or Zeeland.

The apparent lack of empathy might be due to the strict discipline imposed in the Spanish army to prevent sackings and massacres. This discipline meant that, in the roughly four months since the surrender, Antwerp had a chance to recover without interruption. Furthermore, the sixteenth century was a violent era, with the Reformation fuelling religious conflicts. Kiechel may have considered it wise to remain silent on specific issues. Perhaps he did not even notice anything amiss. The traveller had not seen the city before the siege and had nothing to compare it to. He had visited other places in both the Spanish Netherlands and the Dutch Republic, where he noticed dilapidated or damaged houses. Witnessing such scenes in a conflict zone might have been nothing unusual for him, as was the presence of soldiers in all larger settlements.

Antwerp, 1636

Our traveller stayed in Antwerp for eight days, until 10 December. He spent his time searching for a new group to travel with to Aachen and then onwards to Cologne. His previous companions, with whom he had travelled since London, had reached their destination.

Eventually, he found five travellers: a messenger, a merchant from Aachen, another merchant from Italy who had his house in Antwerp, a merchant from Cologne, and one from Frankfurt am Main. The group left Antwerp on 10 December for Mechelen.

Illustrations & References

All images are in order of appearance with links to sources on external websites:

- Wildens, Jan, Panoramic View of Antwerp from the East, 1636; Rijksmuseum Amsterdam.

- van den Hoecke, Robert, Soldaten bij een weg, 1632 – 1668; Rijksmuseum Amsterdam.

- Ghent, in: van Deventer, Jacob, Planos de ciudades de los Países Bajos, Parte II [Manuscrito], fol. 40, 1545; Biblioteca Digital Hispánica.

- Ghent, in: Braun, Georg, Hogenberg Frans, Civitates Orbis Terrarum (1), Cologne 1593, fol. 15v; Heidelberg University.

- van Goyen, Jan, Veer, 1606 – 1656; Rijksmuseum Amsterdam.

- Hogenberg, Frans, Dijken doorgestoken bij Antwerpen, 1585; Rijksmuseum Amsterdam.

- Antwerp, in: Braun, Georg, Hogenberg Frans, Civitates Orbis Terrarum (1), Cologne 1593, fol. 17v; Heidelberg University.

- Antwerp, in: Braun, Georg, Hogenberg Frans, Civitates Orbis Terrarum (5), Cologne 1599, fol. 27v; Heidelberg University.

- Anonymous, De schipbrug van Parma over de Schelde, 1585; Rijksmuseum Amsterdam.

- Wildens, Jan, Panoramic View of Antwerp from the East, 1636; Rijksmuseum Amsterdam.

- Die Reisen des Samuel Kiechel aus drei Handschriften, K. D. Haszler (ed.), Stuttgart 1866, p. 39; Bayerische Staatsbibliothek. ↩︎