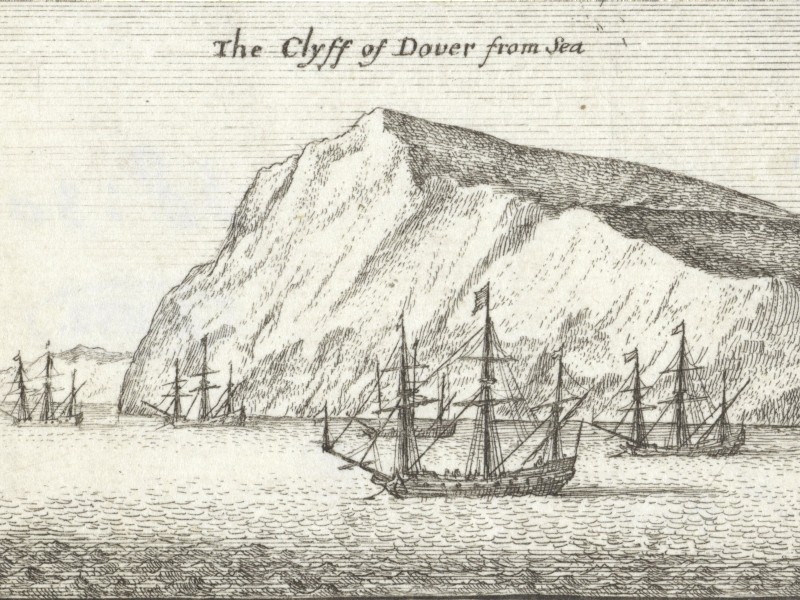

“On 8 September, we spotted land. It was England. The wind was favourable for us to sail close to the harbour, known as Dover. The captain did not wish to enter the harbour and kept the ship at sea, one German mile from the coast.“1

From Vlissingen to London

6 September – 11 September 1585

Samuel Kiechel had spent a month in Vlissingen, waiting for the wind to turn so he could sail to England. Finally, on 6 September, the weather changed, and our traveller boarded a French ship to leave. While England was his destination, he had not been able to obtain a permit to travel there. Samuel was tired of waiting in Vlissingen. He had a passport to France and decided to travel there and cross the channel from a French port.

To England

The ship remained overnight at anchor in the port of Vlissingen, waiting to see if the weather would stay stable. The next morning, the crew set sail with a favourable wind coming from the east. Because of bad weather, no ships had left for England, France, Scotland or Ireland in the past four weeks. On that day, about sixty vessels left the harbour.

When the ship passed Sluis on the coast of Flanders, five miles out at sea, the wind changed direction and began blowing from the west. All other vessels that had left Vlissingen turned back. But not the ship with our traveller on board and one other privateer. According to Kiechel, the two remaining privateers did not care how much time they spent at sea or where they were headed.

The passengers on board had to spend their time on deck because soldiers occupied the hold, preventing anyone from going below. Kiechel described the sailors and soldiers on board as careless and godless. During the night, the weather turned rough, and everyone on deck was soaked from the spray.

Arriving in Dover

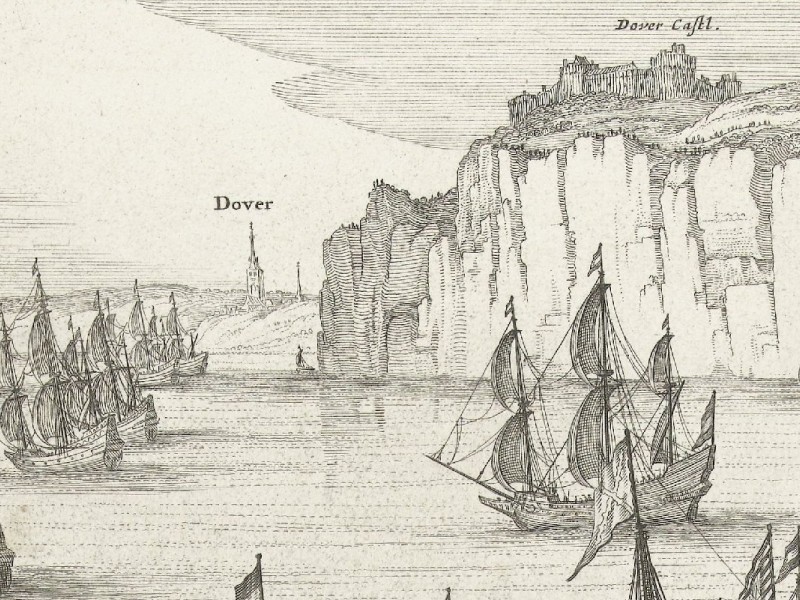

Dover and Dover Castle from the sea

On 8 September, the English coast appeared on the horizon. Although the ship was originally headed for France, shifting winds had blown it off course. Kiechel, who wished to travel to England, did not mind. The wind was favourable, and the ship arrived near Dover on the same day. Three large, armed vessels were at anchor in the harbour; they belonged to the Queen of England. The captain of Kiechel’s ship fired a salute.

Since the privateer was meant to sail to France, its captain decided to anchor outside the port, about one German mile off the coast. After the ship had dropped anchor, a small boat was sent from the harbour to pick up passengers. Kiechel paid the captain and left the vessel along with five Frenchmen. Many other passengers wanted to disembark in Dover, but as the boat was too small, the rest had to wait for its return.

Kiechel describes Dover as unfortified and situated on the coast. On a hill on the right-hand side was a castle that protected the town and its port.

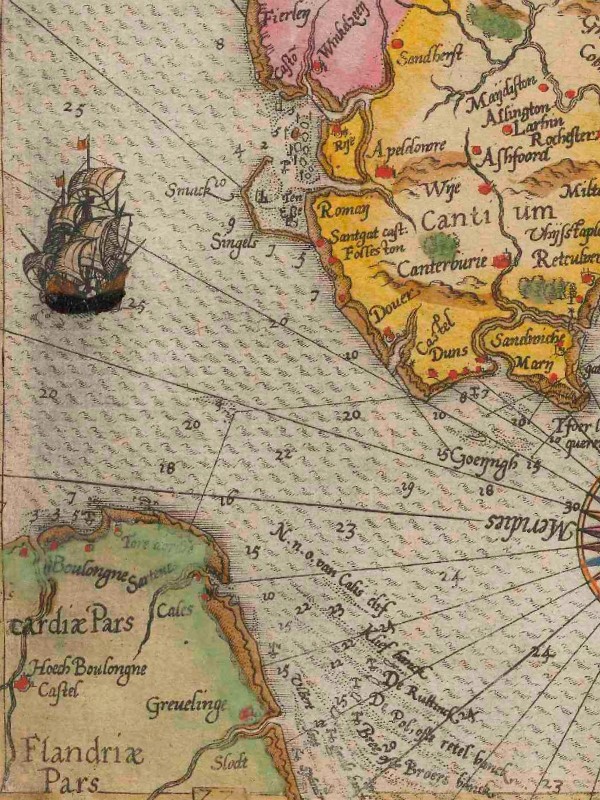

The English Channel with Dover to the right and the French coast to the left

The castle was Dover Castle. A drawing by Anton van den Wijngaerde from 1559 offers a rare glimpse of how Dover might have appeared to the traveller. The image is displayed on the website of the Ashmolean Museum in Oxford. The drawing shows Dover in profile from the sea, with the town nestled between the cliffs. Dover Castle is on the right side, and some harbour facilities are depicted on the left in the foreground. Various ships are in the harbour, while others are anchored at sea.

The small boat with Kiechel and the other passengers arrived in the harbour. The travellers disembarked and headed for the inn. Shortly after their arrival, some official-looking men came to the inn to question all new arrivals. Kiechel had to state his name, where he had come from, where he intended to go and the purpose of his visit to England. He learned that if a person carried letters for merchants or others in the country, they must show these letters to the royal officials. Messengers are required to present all the letters they carry into or out of the country. If the officials suspect a letter, they may open it. If they are suspicious of a person, they can arrest them. Kiechel concludes that, thanks to the vigilance of these officials, much treachery is uncovered.

Dover was the primary entry point for travellers from the continent and a major harbour on the Channel coast. Security in the town was tight, as Kiechel described. The French city of Calais was only a few kilometres away, and the Spanish Netherlands was not far off either. Additionally, England had recently entered the Eighty Years’ War on the side of the Dutch Republic and was therefore at war with Spain.

The fears during this period extended beyond political intrigue and espionage; religious subversion was another significant threat. Memories of the turmoil under Mary I (1516-1558) were still vivid. Mary, the half-sister of Elizabeth I, ascended to the throne in 1553. As a devout Catholic, she began to reverse the Protestant policies established by their father, Henry VIII (1491-1547), who had broken away from the Pope to establish the Church of England, marking the start of the English Reformation. Under Mary’s rule, Protestants were declared heretics; many fled the country, while others were executed by burning at the stake. Additionally, her marriage to Philip II of Spain was deeply unpopular, as many feared it would make England dependent on the Habsburg Empire.

Mary’s reign was brief. By 1558, she fell ill and died without an heir, which led to Elizabeth’s accession to the throne and her coronation in 1559. Queen Elizabeth I (1533-1603) firmly established England as a Protestant Kingdom. However, the threat of Catholic influence persisted, particularly with Spanish territories across the Channel. The work of the immigration officials, who questioned all new travellers arriving at Dover, was also aimed at preventing Catholic propaganda from entering the country.

To London

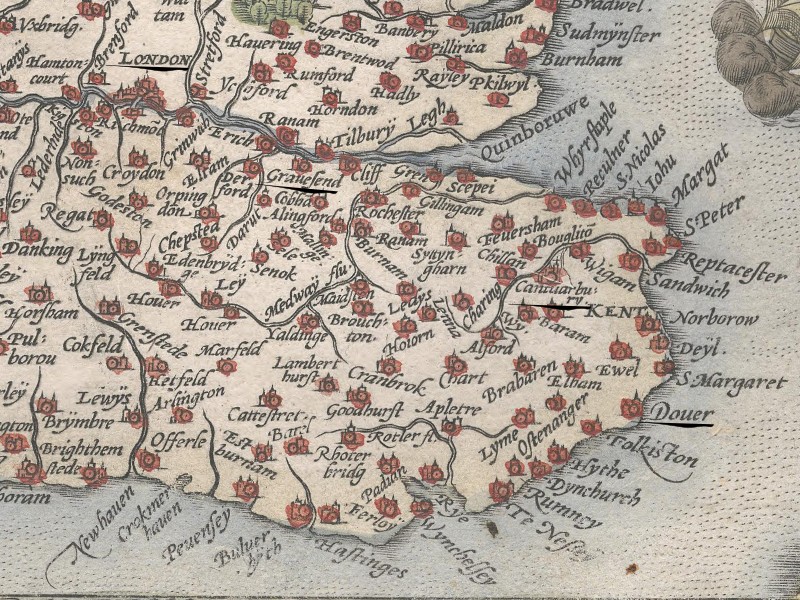

Samuel Kiechel’s route from Dover to London

Kiechel spent a day in Dover looking for someone to accompany or guide him to London. The next morning, he set off with a messenger. Unfortunately, neither spoke the other’s language, so Kiechel could not ask about the places they passed on their way to the capital.

At lunchtime, the travellers stopped at Canterbury. Although Kiechel does not mention anything specific about the city, a bird’s-eye view of it is included in volume four of the “Civitates Orbis Terrarum”. The illustration depicts a small town surrounded by walls, with only a few houses visible. However, the cathedral is easily recognised.

Canterbury, 1588

In the evening, our traveller arrived in Sittingbourne, a small unfortified town twenty-four English miles from Dover.

The distances mentioned in Kiechel’s journal can be confusing. The length of a mile varied not only between countries but also among provinces and territories. Kiechel explains that an English mile is about a fifth of a German mile and similar to an Italian mile. However, Daniel Wintzenberger, a messenger of the Prince-Elector of Saxony, who had extensive knowledge of distances, wrote in his guidebook that five English miles equal three German miles. In turn, one German mile equals five Italian miles or two French miles.2

In addition to the wildly varying definitions of a mile, it is important to remember that the known distances between places were rarely determined through systematic surveys, as they are today. Instead, distances were often estimated based on the experiences of those familiar with the area, the time it took to travel from one place to another and some degree of guesswork.

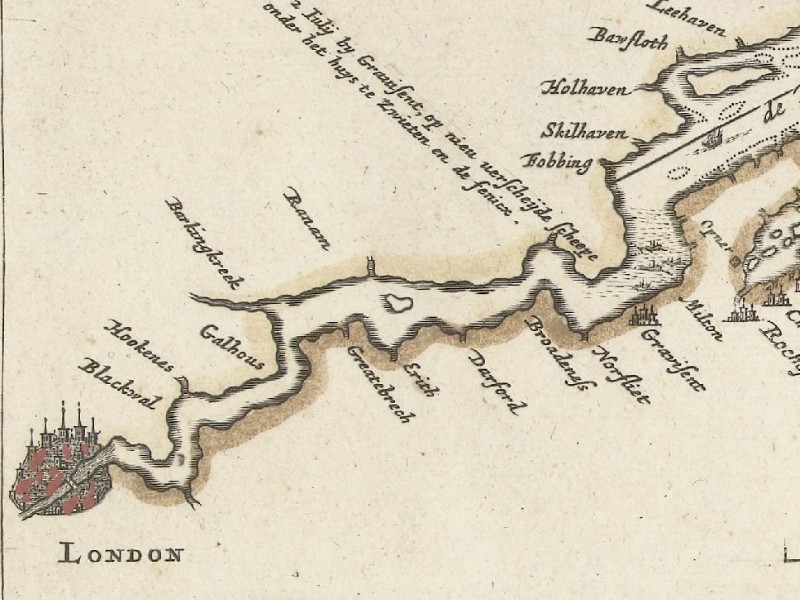

Samuel Kiechel spent the night in Sittingbourne. He and the messenger continued their journey the following morning, arriving in Gravesend around lunchtime. According to our traveller, this town was located on an arm of the sea that extended all the way into London (the Thames).

Kiechel’s route from Dover to London followed one of the three major postal routes established in the early sixteenth century. The other two routes connected London to Berwick on the Scottish border and to Plymouth in the southwest. The route from Dover passed through Canterbury, Sittingbourne, and Rochester before reaching Gravesend. At Gravesend, travellers changed transport to continue the journey to the capital by boat. This boat connection to London was known as the Long Ferry.3 Kiechel noted that boats travelled back and forth daily between Gravesend and London, but their schedule depended on the tide. He had to wait until the evening for a boat to depart when the tide turned. He then boarded with seven other passengers and two oarsmen.

London, Billingsgate

Due to the late departure, the boat arrived in London at midnight. Samuel Kiechel recalls stepping onto the pier just as the bells rang. Arriving in an unfamiliar city in the middle of the night presented a challenge. Samuel did not know where to go and had no place to spend the night. After wandering around, he eventually found a bakery. Although it was Saturday night, the baker was still busy preparing for Sunday. Fortunately, the man spoke French and kindly allowed him to stay in the bakery for the rest of the night.

Illustrations & References

All images are in order of appearance with links to sources on external websites:

- Hollar, Wenceslaus, The Clyff of Dover from Sea, 1625 – 1677; Rijksmuseum Amsterdam.

- van Eertvelt, Andries, Ships in a Storm, 1600 – 1652; Rijksmuseum Amsterdam.

- Workshop of Claes Jansz. Visscher, De grote zeeslag bij Duins (plaat 1), 1639; Rijksmuseum Amsterdam.

- Waghenaer, Lucas Jansz., Thresoor der zeevaert, inhoudende de geheele navigatie ende schip-vaert vande Oostersche, Noordtsche, Westersche ende Middellantsche Zee, met alle zee-caerten daer toe dienende …, Amsterdam 1596, fol. 76v; Utrecht University Repository.

- Anonymous, Nachtwakers fouilleren een man, 1613 – 1667; Rijksmuseum Amsterdam.

- Ortelius, Abraham, Theater of the World, Antwerp 1587, fol. 11v; Library of Congress.

- Canterbury, in: Braun, Georg, Hogenberg, Frans, Civitates Orbis Terrarum (4), Cologne 1594, fol. 1v; Heidelberg University.

- Anonymous, The Dutch Raid on the Medway, 1667; Rijksmuseum Amsterdam.

- Visscher, Claes, Londinum florentissima Britanniae urbs, 1616; Folger Shakespeare Library.

- Die Reisen des Samuel Kiechel aus drei Handschriften, K. D. Haszler (ed.), Stuttgart 1866, p. 21; Bayerische Staatsbibliothek. ↩︎

- Wintzenberger, Daniel, Ein Naw Reyse Büchlein von der Weitberümbten Churfürstlichen Sechsischen Handelstad Leiptzig, Dresden 1595. ↩︎

- Mortimer, Ian, The Time Travellers Guide to Elizabethan England, London 2021, pp. 200-201. ↩︎