Map of the Europe, 1587

Imagine you are a traveller from southern Germany travelling through sixteenth-century Europe. You arrive in London, a rapidly expanding commercial centre at the time. Standing in the harbour, you watch ships arrive, carrying spices, silk and other exotic goods that, just a century earlier, would have only been available in small quantities at exorbitant prices. Consider the impact that such a lively port, bustling with people from different places, would have on someone coming from a landlocked, inward-looking city in the Holy Roman Empire that was still struggling with the religious tensions of the Protestant Reformation. Now, add to this the constant flow of news and rumours — stories of events across Europe, kings and queens, frightening tales of plagues, banditry, and war, or about distant, fantastical places like India and the West Indies that spark the imagination.

A traveller who had experienced this was Samuel Kiechel (1563-1619). Kiechel, a young man from the southern German city of Ulm, left his home in 1585 for a four-year journey through parts of Europe and the eastern Mediterranean. By the time he returned, he had covered over 30,000 kilometres (approximately 19,000 miles). During his journey, Kiechel witnessed a world in transition. The sixteenth century was a pivotal period in European history, marked by transformations that reshaped the continent’s political, social, economic, and cultural landscapes. This era saw significant advances in exploration and science, the flourishing of Renaissance art and culture, the Protestant Reformation, and the rise of powerful dynasties.

The Age of Exploration

By the late sixteenth century, European sailors and navigators had ventured far beyond their familiar shores in search of new sea routes to the wealthy markets of Asia. The desire to explore the world beyond known frontiers began in the mid-fifteenth century when Portuguese ships sailed along the west coast of Africa. Vasco da Gama successfully rounded the Cape of Good Hope and reached India in 1498. His discovery provided Portuguese merchants with direct access to commodities like spices and silk. It decreased the European market’s reliance on Italian, Ottoman, and Arab intermediaries who controlled the old land routes to Asia. Western merchants also engaged in the sea trade along the Indian Ocean coast, soon dominating it by establishing trading posts and colonies.

While the Portuguese dominated the maritime route around Africa, the Spanish fleets sailed west. Christopher Columbus arrived in the Caribbean in 1492. The Spanish explored and conquered Central and South America, established colonies, and extracted vast quantities of gold and silver from their conquests in Mexico and Peru. The wealth generated from these colonial enterprises enabled Spain to finance wars and expand its influence in Europe.

By the end of the sixteenth century, France, England, and the Netherlands entered the race for colonies. The world had opened up for Europeans. Conflicts were no longer fought solely within Europe’s continental borders; they extended across the globe. Politics, trade, and the exploitation of overseas colonies hinged on control of sea routes. A powerful navy became just as crucial as having dominant land forces, as the Dutch and the English would eventually demonstrate.

Economic, Social and Cultural Changes

The influx of valuable minerals and new commodities from overseas possessions transformed Europe’s economy. As more gold and silver entered circulation, prices for goods rose significantly, impacting economies across the continent. Along with increased wealth came new economic policies advocating state intervention, promoting exports, and reducing imports (Mercantilism). Monarchs sought to centralise their authority through institutional reforms and by establishing effective bureaucracies.

For centuries, the Italian city-states held a monopoly on the trade of exotic goods. Spices, silk, and other valuable commodities arrived from Asia at trading ports in the eastern Mediterranean, where Italian ships, especially Venetian ones, collected them. As the world opened up, trade and commerce moved from the Mediterranean to the Atlantic coast, leading to the rise of commercial centres such as Antwerp, Amsterdam, and London. Having lost their dominant position in the spice trade, the Italian city-states turned their attention to banking and financial services instead.

The changing economic landscape put pressure on existing social structures. In particular, urban dwellers found more opportunities in thriving cities filled with artisans and merchants. Wealthy citizens began challenging traditional aristocratic privileges, and the increasing demand for skilled individuals in expanding administrative institutions created new prospects for them. Their wealth and often superior education gave them political influence and access to roles previously reserved solely for the nobility.

One aspect of the expanding opportunities for merchant families was the chance to undertake educational journeys, such as the one Samuel Kiechel was about to start. Successful journeys — meaning the traveller returned alive and healthy — brought prestige among peers and offered career advantages.

The fifteenth and sixteenth centuries are known as the Renaissance, a period characterised by a desire to reconnect with the classical scholarship of ancient Greece and Rome. The focus of education shifted away from mainly theological matters, and secular scholars gained prominence over clerics. Notable figures of this period include Leonardo da Vinci, Michelangelo, and Galileo Galilei.

With this shift came important technological inventions. The most influential of these innovations was the printing press. It played a vital role in spreading both new ideas and classical knowledge across Europe. Many ancient Roman and Greek works, which had survived the Middle Ages in the Byzantine Empire and the Arab world, were collected, translated, and published.

Cartography and mapmaking also saw notable progress during this era. Abraham Ortelius published the first modern atlas, “Theatrum Orbis Terrarum”, in 1570. Meanwhile, Georg Braun and Frans Hogenberg released their multi-volume work, “Civitates Orbis Terrarum” (Cities of the World), between 1572 and 1617. Both of these publications contributed to the reconstruction of Samuel Kiechel’s journey.

The Protestant Reformation

One of the most significant events of the sixteenth century was the Protestant Reformation. While influenced by the Renaissance on one hand, the reformers nonetheless criticised its secular effects on the Catholic Church, especially regarding the actions of the popes of that time. Their primary concern was the corruption and misuse of the Church’s finances, including the sale of indulgences.

The movement was initiated by Martin Luther’s Ninety-Five Theses in 1517 and quickly gained momentum across Christian communities in northern and central Germany. Luther’s initial focus on the sale of indulgences broadened into broader doctrinal debates, ultimately leading him to question the Pope’s authority. This dispute caused a significant religious split within the Christian Church.

The printing press was pivotal in the rapid spread of Reformation ideas. Luther’s ability to utilise it effectively allowed him to quickly publish and distribute his Theses, along with subsequent treatises, pamphlets, and arguments. This capacity for rapid publication ensured that Luther’s voice remained influential and that the ideas of the Reformation spread swiftly. Various reformers appeared across different regions during this period: John Calvin in Geneva promoted the concepts of predestination and a strict moral code, while Huldrych Zwingli advocated for a more radical break from Catholic traditions. By the late sixteenth century, Protestantism had extended beyond the Empire’s borders to reach the Baltic Sea region, Scandinavia, and the Low Countries.

The Habsburgs

Travelling through sixteenth-century Europe often meant passing through the territory of the Habsburg Dynasty. The rise of the Habsburgs began with Maximilian I (1459-1519), who expanded the family’s influence through diplomacy, warfare, and strategic marriages. He married Mary of Burgundy in 1477, and upon her death in 1482, he inherited the Burgundian Netherlands. Maximilian reclaimed Burgundian territories from France by conquering the provinces of Artois and Flanders. His father, Frederick III (1415-1493), served as Emperor of the Holy Roman Empire, and to secure his succession, Frederick arranged for his son to be elected and crowned King of the Romans (Germany) in 1486. Upon Frederick’s death in 1493, Maximilian eventually became Emperor in 1508.

Maximilian I (1459-1519)

Maximilian and Mary of Burgundy had a son, Philip (1478-1506). Philip married Joanna of Castile in 1498. Joanna had become the heiress to the thrones of Castile and Aragon after the deaths of her older siblings. This marriage established the Habsburgs in Spain.

Charles V (1500–1558)

Philip died in 1506 at the age of twenty-eight, and his son Charles became King of Spain and Lord of the Burgundian Netherlands. Charles also inherited the Habsburg ancestral lands, the Duchy of Austria and the Kingdoms of Naples and Sicily. He followed his grandfather Maximilian on the throne of the Holy Roman Empire, being elected and crowned King in 1519 and later becoming Emperor in 1530.

Under Emperor Charles V (1500–1558), the Habsburgs ruled over a vast domain that included significant portions of Europe and the Spanish colonies in the Americas. Although the dynasty remained influential, only Charles ruled this empire alone. After his abdication in 1556, the Habsburg dynasty split into two branches: the German-Austrian line and the Spanish line. Charles’ son, Philip II (1527-1598), inherited the Spanish throne, the Spanish colonies, the Netherlands, and territories in Italy, while Charles’ brother Ferdinand, who had already been elected King of the Romans in 1531, inherited the Duchy of Austria and became Emperor in 1558.

At the time of Samuel Kiechel’s journey, Rudolf II (1552–1612), the grandson of Charles V, was the Holy Roman Emperor. Rudolf was an indecisive and ineffectual ruler at a time when the Empire needed a more energetic leader. However, he was a knowledgeable and actively interested patron of the arts and sciences. He moved his residence from Vienna, the Habsburg heartland, to Prague, where his court became a centre of culture and scholarship.

The Holy Roman Empire

Our traveller, Samuel Kiechel, came from Ulm in the Holy Roman Empire (Germany). Unlike other realms in Europe where monarchs were consolidating their power, attempts to strengthen and centralise imperial authority had failed. It existed as a patchwork of large and small territories and free cities. The regional princes often ruled their lands almost independently.

The Empire was an elective monarchy, and a college of seven clerical and secular princes, known as Prince-Electors, held the power to elect the future King, who would then become Emperor. Although the princes frequently clashed, they usually found common ground in opposing any attempts by the King or Emperor to limit their influence. Due to the fragmented structure of his domain, the Holy Roman Emperor was not as powerful as the title might suggest. Nevertheless, despite the varying ambitions of the nobility, the Empire remained intact, and its institutions functioned effectively. Since 1438, the Emperor has been from the Habsburg Dynasty.

As the birthplace of the Protestant Reformation, the Holy Roman Empire experienced significant religious tensions in the sixteenth century. Within its loose confederation of semi-autonomous territories, Martin Luther’s ideas spread rapidly. At the Diet of Augsburg in 1530, the “Confessio Augustana” (Augsburg Confession) was presented to Emperor Charles V. This document contained twenty-eight articles outlining the primary principles of the Protestant faith. Charles rejected the “Confessio,” and tensions escalated until they culminated in the Schmalkaldic War in 1547. The Protestant Princes lost this conflict, but Charles’ botched attempts to reintegrate them into the Catholic Church led to renewed resistance.

Diet of Augsburg, 1530

In 1555, Charles’ brother Ferdinand negotiated the Peace of Augsburg. This treaty temporarily resolved the religious conflict between Protestants and Catholics by allowing the ruler of each territory to choose the faith practised within their domain. Lutheranism was officially recognised as a legal confession in the Empire. The Peace of Augsburg remained in effect until the outbreak of the Thirty Years’ War (1618-1648), one of the most devastating conflicts of the period.

European Countries in the Late Sixteenth Century

In the northwest of Europe, England was governed by Elizabeth I (1533-1603). A daughter of Henry VII, she came to power in 1558 following the brief and tumultuous rule of her half-sister Mary. Elizabeth’s long reign of over forty years helped stabilise the kingdom once more, and Protestantism became the official religion. Her time as Queen of England was marked by significant events that remain well-known today. In 1580, Francis Drake returned after successfully circumnavigating the globe. Mary, Queen of Scots, faced trial and was executed in 1587. The following year, an English fleet triumphed over the Spanish Armada, setting the course for Britain to dominate the seas. By the end of the decade, playwright William Shakespeare entered his most productive period. Additionally, Elizabeth was an early modern tourist magnet. Like many other travellers of the time, Samuel Kiechel was eager to catch a glimpse of her.

The Dairy Cow: The cow symbolises the rebellious provinces. Philip II of Spain rides it, the Prince of Orange milks the cow, the Duke of Anjou pulls its tail, Queen Elizabeth feeds the animal, and a deputation from the States-General seized it by the horns.

Regarding foreign policy, Elizabeth backed the Protestant Dutch provinces in their war (Dutch Revolt/Eighty Years’ War, 1568-1648) against Spain. The Netherlands had been part of the Habsburg Empire since 1482. Following the abdication of Charles V in 1555, the region fell under the control of Charles’s son, Philip II, who ruled from Spain. Increased taxation, marginalisation of the local nobility in favour of Spanish and Italian noblemen, and religious repression against the Calvinist population by the staunchly Catholic Philip led to rebellion and a push for independence by the northern Dutch provinces.

Trade was the backbone of the prosperity of the young Dutch Republic. As a coastal nation, its inhabitants possessed both the experience in shipbuilding and the capacity to mass-produce new vessels. With improved ship designs, Dutch merchants could outcompete rivals in the European trade network. The wealth generated through trade in Europe allowed the Dutch to fund increasingly daring but often profitable ventures, including entering the spice trade and establishing colonies in Asia.

The late sixteenth century marked the start of the Dutch Golden Age, which continued throughout the seventeenth century. The Dutch relative wealth encouraged scientific progress and a keen interest in the arts and culture. Paintings, especially domestic scenes, maritime subjects, and landscapes, were particularly sought after. Many notable Dutch artists, such as Johannes Vermeer and Rembrandt van Rijn, are linked to this era.

Vermeer, Johannes, ‘The Little Street’, Delft

France in the sixteenth century was characterised by struggles for political stability amid religious conflict, efforts towards centralisation, and economic difficulties. Francis I (1515-1547) strengthened royal authority and aimed to expand French territory in Italy. However, at the Battle of Pavia in 1525, a Spanish army decisively defeated the French and captured Francis, forcing him to give up his claims in Italy. Under his successors, intense religious conflicts between Catholics and Huguenots dominated French politics during the latter part of the century. The St. Bartholomew’s Day Massacre in 1572 led to the deaths of thousands of Huguenots.

In the south, Philip II (1527-1598) was not only the King of Spain but also ruled over a vast empire with colonies around the world. His reign focused on strengthening royal authority, centralising government, and affirming Spanish supremacy in Europe. Philip positioned himself as the defender of Catholicism against the Protestant Reformation sweeping across Europe. He actively supported the Inquisition and aimed to eliminate heresy within his realms.

The wealth from Spanish colonies initially boosted Spain’s economy, enabling extensive military campaigns. However, the wars against France, England, and the Netherlands became exceedingly costly. Philip’s reign saw Spain declare bankruptcy three times (in 1557, 1560, and 1575).

Philip II (1527-1598)

Philip’s aim to maintain Catholic dominance in Europe greatly influenced his foreign policy. He married Mary I of England, who was determined to restore Catholicism in her country. The marriage was unpopular, and many influential nobles feared this union would turn England into a dependency of the Habsburg Empire. After Mary’s death in 1558, a conflict with her sister, Elizabeth I, ensued, leading to military confrontations. In 1588, Philip launched the Spanish Armada against England, intending to overthrow Elizabeth and restore Catholic rule. The failed invasion marked a turning point in naval power and signalled the decline of Spanish dominance at sea.

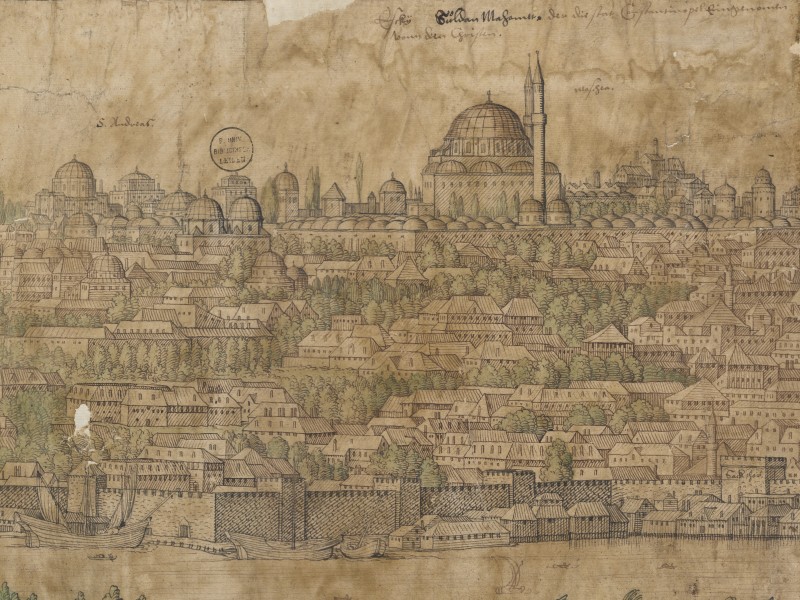

Constantinople, 1559

At the other end of the continent, the Ottoman Empire had reached its peak under Sultan Suleiman the Magnificent (1494-1566). His armies successfully conquered Belgrade and much of Hungary, and in 1529, the Ottomans laid siege to Vienna. However, Suleiman’s successors lacked his political acumen and administrative talents. His grandson, Murad III (1546-1595), ruled over a vast empire, but long-winded military campaigns had exhausted its financial reserves. More interested in a life of pleasure, Murad surrounded himself with scholars and poets and seldom left the palace. His court became rife with corruption and intrigue. Murad delegated the practical aspects of governance to his Grand Vizier. At the same time, the influence of his mother and, later, his favourite concubine grew. Consequently, the Ottoman Empire entered a period of stagnation and eventually fell into a slow decline.

In the northeast of Europe, Ivan the Terrible (1530-1584) ruled Russia until 1584. He was the first Russian ruler to adopt the title of Tsar. Ivan initiated and ultimately lost the long and devastating Livonian War (1558–1583) against the Kingdoms of Sweden and Poland-Lithuania. This war marked the end of a confederation between the Livonian branch of the Teutonic Order and wealthy cities like Riga and Reval (Tallinn), which had long monopolised European trade with Russia. The conflict thoroughly devastated the prosperous region. Samuel Kiechel visited Livonia in 1586 and witnessed its desolate state.

In 1581, Ivan killed his first son, who was his designated heir, in a fit of rage. Upon his death in 1584, he left the empire to his second son, Feodor. Unprepared to rule, Feodor allowed his advisers to handle the business of governance. Childless himself, Feodor’s death in 1598 marked the end of the Rurikid Dynasty. After a period of political turmoil, the Romanovs ascended to the Russian throne in 1613.

Illustrations & References

All images are in order of appearance with links to sources on external websites:

- Ortelius, Abraham, Theater of the World, Antwerp 1587, fol. 2v; Library of Congress.

- Visscher, Claes Jansz., Handel en koopvaardij, 1608; Rijksmuseum Amsterdam.

- van Cleve, Joos, Portrait of Maximilian I (1459-1519), Emperor of the Holy Roman Empire, c. 1530; Rijksmuseum Amsterdam.

- Anonymous, Portret van Karel V van Habsburg, Duits keizer en koning van Spanje, 1519; Rijksmuseum Amsterdam.

- Lodewyck, Hendrick, Rijksdag van Augsburg (1530), 1634; Rijksmuseum Amsterdam.

- Anonymous, The Dairy Cow: The Dutch Provinces, Revolting against the Spanish King Philip II, Are Led by Prince William of Orange, The States General Entreat Queen Elizabeth I for Aid, c. 1633 – c. 1639; Rijksmuseum Amsterdam.

- Wierix, Antonie, Portret van Filips II, koning van Spanje, 1565 – 1604; Rijksmuseum Amsterdam.

- Lorck, Melchior, Prospect of Constantinople, part 13, 1559; Leiden University Libraries.