“I arrived in the evening in Leipzig. Leipzig belongs to the Elector of Saxony. It is a beautiful, well-built and pleasant city. Much trade is taking place there because of the trade fair three times a year. The city has a university.“1

From Dresden to Leipzig and Halle

10 June – 15 June 1585

In present-day Saxony, Dresden functions as the seat of the federal government and is celebrated for its baroque architecture and cultural treasures. Leipzig, by contrast, is the centre of commerce, trade fairs, and art.

It was not very different in the sixteenth century. Although the Baroque period had not yet arrived, Dresden was the residence of the Prince-Elector and had been developed as a representative seat of government. Leipzig was well known for its fairs, which brought wealth and prosperity to the city. After visiting Dresden, Samuel Kiechel was now on his way to Leipzig. He would also stop in Halle, a place famous for its salt production.

On the Road to Leipzig

Samuel Kiechel stayed in Dresden for one night. He left on 10 June in the same postal carriage he had arrived in. The carriage drove north along the Elbe to the town of Meissen, where it arrived at lunchtime.

Meissen, 1575

Kiechel mentions that the Land of Meissen took its name from this city. Meissen dates back to 929, when Henry I (876–936), King of East Francia, built a castle during a campaign against Slavic tribes in the region. Around the castle, a town grew. In the second half of the tenth century, the Margraviate of Meissen was established as a border province of the Holy Roman Empire. The Bishopric of Meissen was founded in 968 to baptise the Slavic tribes between the Elbe and Oder rivers.

As the political and religious centre of the region, Meissen became a significant influence in the development of what would eventually be the Duchy of Saxony. However, the Margraviate of Meissen lost its status as an independent principality and became part of the Duchy in 1423. The name remained in use for one of the administrative districts of Saxony (“Meißnischer Kreis”, District of Meissen). In 1471, the Albrechtsburg, the first purpose-built palace in Germany, was constructed on the foundations of the much older medieval castle. The Albrechtsburg, with its unique architectural features and historical significance, is one of the city’s main attractions today.

Samuel Kiechel did not stay and continued to Oschatz in the afternoon. Oschatz was seven miles from Dresden, and our traveller spent the night there. The following day, Kiechel continued his journey in the carriage. He passed through Wurzen and arrived in Leipzig.

The route through Meissen, Oschatz and Wurzen was one of two major roads between Dresden and Leipzig mentioned in the itineraries. Daniel Wintzenberger’s “Reyse Büchlein” (1578) lists Meissen, Lommatzsch, Mügeln and Grimma as the towns along the second route to Leipzig.2

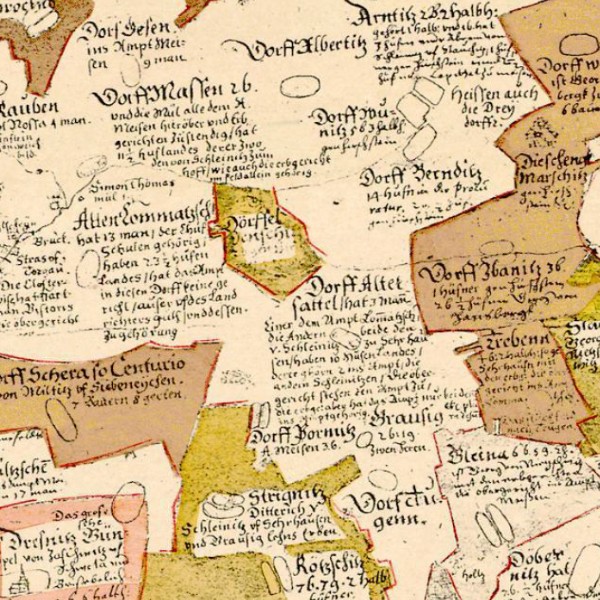

The land between Meissen and Leipzig on the Oeder-Map

The survey maps of Saxony show the landscape between Meissen and Leipzig. This part of the Duchy had a higher density of settlements than the area between the Ore Mountains and Dresden. The landscape consisted of a regular network of villages and fields. The information given in the maps about each settlement is detailed, and it often includes the owner’s name, the size, jurisdiction and occasionally what appears to be the amount of tax to be paid.

Leipzig

Samuel Kiechel’s description of Leipzig is again very brief: The city is under the rule of the Elector of Saxony, and it is beautiful and well-built. Leipzig is a centre of commerce due to the regular trade fairs held three times a year. Kiechel also mentions that Leipzig has a university.

Leipzig, 1618

This print, a bird’s-eye-view of Leipzig from the southeast, was published in volume six of the “Civitates Orbis Terrarum” in 1618. While Kiechel had visited Leipzig thirty-three years earlier, it is reasonable to assume that not too much had changed in the intervening years. Construction work in the early modern period was slow, and outside of major disasters, the appearance of a city changed gradually. The event that would reshape many German towns in the early modern period, the Thirty Years’ War (1618 – 1648), was still to come.

The view presents Leipzig as a densely populated, sprawling city with suburbs. It is fortified by a wall and surrounded by a moat. A table in the lower-left corner of the image identifies eighteen buildings.

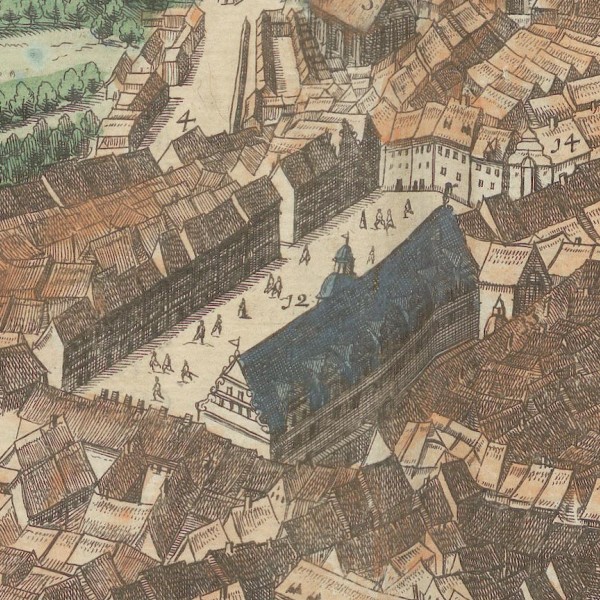

The Pleissenburg and St. Peter’s Gate of Leipzig, 1618

On the left side of the view is the Pleissenburg (“1. Arx Pleissenburgum”). The castle had been built in the thirteenth century. During the Schmalkaldic War, Leipzig came under siege.3 The city held out, and after the siege, its fortifications and the Pleissenburg were rebuilt and strengthened. The Moritzbastei is the only part of the new fortifications you can still visit today. The Pleissenburg was demolished in 1899, and the city council had the New Town Hall built in its place.

Further buildings emphasised in the view are the Old Town Hall (“12. Curia”), St. Nicolas Church (“15. Templum S. Nicolai”) and the university (“8. Collegium novum, 9. Collegium magnum”). Visitors to Leipzig can still see both the Town Hall and St. Nicolas.

Market Square and Old Town Hall

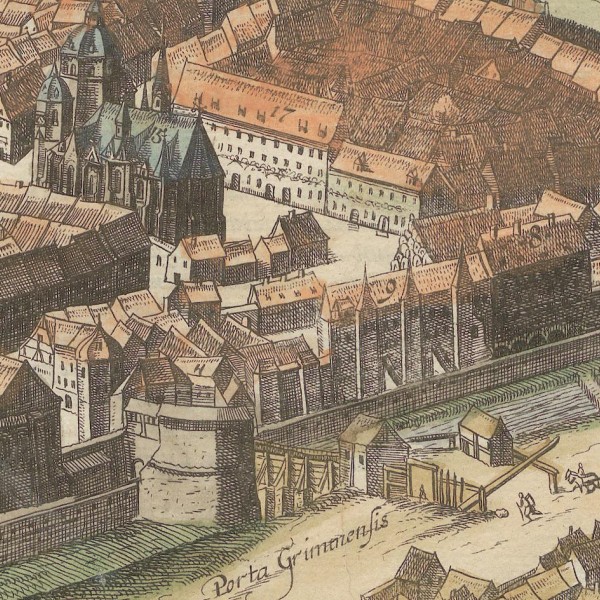

Grimma Gate, St. Nikolas Church and “Collegium magnum” (Large College)

Kiechel mentioned the university but did not provide any details. Leipzig University was founded in 1409 and is now one of the oldest universities in Germany. Besides the two buildings mentioned above, the “Collegium Paulinum” and “Templum Paulinum” were also part of the university. Both buildings had belonged to a Dominican monastery. When Leipzig became Protestant, the monastery was secularised, and the buildings were donated to the university.

The university buildings and St. Nicolas Church were close to the southeastern gate of Leipzig (“Porta Grimmensis”). Samuel Kiechel had arrived from this direction and probably entered Leipzig through this gate.

The Leipzig Trade Fair

Samuel Kiechel mentioned that Leipzig’s wealth came from its trade fairs. Fairs were an essential fixture of economic life in medieval and early modern Europe. They were often held during a religious festival to attract more visitors. The Carolingians were the first to establish large fairs in their Empire. The Champagne fairs were the most prominent medieval trade fairs. They took place six times a year in various towns in the province of Champagne between the eleventh and fourteenth centuries. The fairs attracted long-distance traders from across Europe. They brought goods like textiles, furs and spices. In northern Europe, a large fair was regularly held on the coast of Skåne (Sweden) during the herring season.

In the late Middle Ages, more and more European cities held large fairs. Those cities, like Cologne, Frankfurt/Main and Leipzig, were usually at the crossroads of major trade routes. Due to their economic importance, the major trade fairs held special privileges. Visiting merchants and their goods were protected, and, if necessary, they received an escort.

The trade fairs of Leipzig have a long history. They took place at Jubilate, Michaelis and New Year (Jubilate = third Sunday after Easter, Michaelis = 29 September). In contrast to the fairs regularly held in most towns and cities of the region, the Leipzig trade fair was protected by imperial privilege. Emperor Maximilian declared them imperial fairs in 1497. Maximilian confirmed the privilege in 1507 and set out additional stipulations. The Leipzig trade fairs became not only a hub for commerce but also a place for cultural exchange and the dissemination of knowledge. From then on, it was prohibited to hold fairs in a fifteen-mile radius around Leipzig (about 115 kilometres), all the roads to and from the city had to be kept open and confiscating or taking goods destined for the fair was considered a crime.

Halle

A gate in the upper right corner of the bird’s-eye view of Leipzig is the “Porta Halensis.” The road through this gate led to the city of Halle, approximately thirty kilometres northwest. It was Samuel Kiechel’s next destination, and on 12 June, he departed Leipzig and walked there along a pleasant road. Our traveller noted that the administrator (of the Bishopric of Magdeburg) resided in Halle and that he was the son of the Elector of Brandenburg.

An administrator was an elected bishop. After the Reformation, the Catholic cathedral chapters of some dioceses converted to Protestantism and elected their new bishops. The Protestant bishops would no longer gain papal approbation and were usually called administrators. The city of Halle had been part of the Archbishopric of Magdeburg and became Protestant in 1567. The administrator mentioned by our traveller was Joachim Friedrich of Hohenzollern (1546 – 1608), son of Johann Georg (1525 – 1598), Elector of Brandenburg.

Halle, 1599

In this view of Halle from the west, the river Saale is in the foreground. We see a large city with many notable buildings. On the left side of the image is the castle Moritzburg (“Die Moritzburg das Schlos”). The castle had been built in the late fifteenth century and was the residence of the Archbishops of Magdeburg from 1503 to 1545. In 1545, the Archbishop moved his residence to the newly built New Residence (“Das new gebew”) seen in the centre left of the view. Halle Cathedral (“Der Thum”) is to the left of the New Residence.

In the centre of the view is the Market Church of Our Dear Lady (“Unser lieben Frawen Pfarkirch”) and the Red Tower (“Der rote Thurn”). The Red Tower and the four towers of the church dominate the skyline of Halle to this day. The town hall and granary are to the right of the Market Church. Both buildings are only distinguishable from the surrounding houses by their names written above. To the right are three more churches (“Sanct Uldrich”, “Sanct Mauritz”, “Sanct Georgen”) and the city’s sawmill (“die brett Mühl”).

The wealth of Halle came from its salt. Salt was a valuable commodity in the early modern period. In a time when refrigeration was unknown, salt was one of the few ways to preserve food.

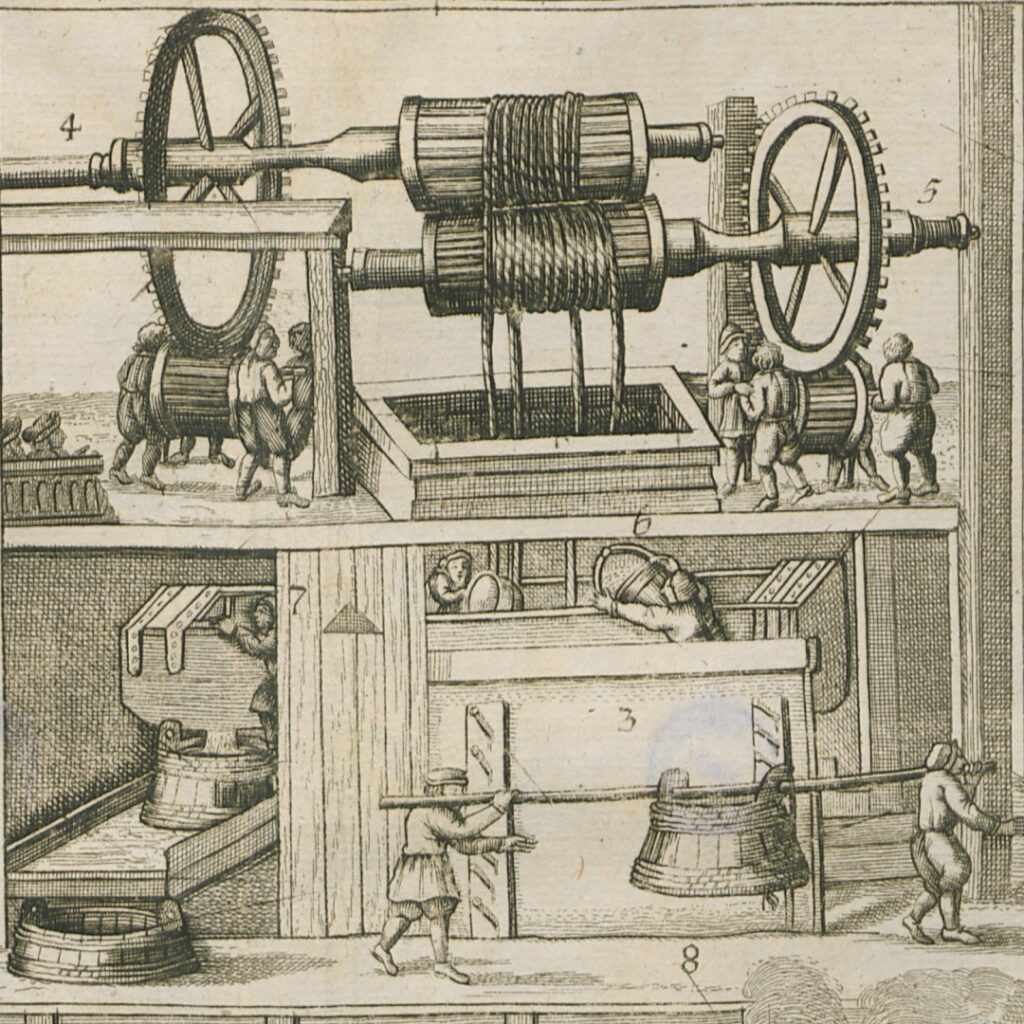

Salt production in Halle, 1670

Halle sits atop a geological fault that allows springs with brine (water with high salt concentrations) to reach the surface. Kiechel wrote that he saw a well that was used for salt production. Four such wells were at the Hallmarkt in the city’s centre: the Deutsche Born, Gutjahrbrunnen, Hackeborn and the Meteritzbrunnen. Workers poured the brine from the wells into large pans and boiled it until the water evaporated and the salt crystals remained. In a treatise about salt production in Halle from 1670, the author Friedrich Hohndorff mentions that salt was produced in 112 houses around the Hallmarkt. The area around the Hallmarkt had its own jurisdiction and administration.4

Samuel Kiechel spent only one night in Halle. On 13 June, our traveller returned to Leipzig. He stayed there two days to look for companions before leaving for Wittenberg.

Illustrations & References

All images are in order of appearance with links to sources on external websites:

- Leipzig, in: Braun, Georg, Hogenberg, Frans, Civitates Orbis Terrarum (1), Cologne 1593, fol. 28v; Heidelberg University.

- Meissen, in: BraunGeorg, Hogenberg, Frans, Civitates Orbis Terrarum (2), Cologne 1575, fol. 44v; Heidelberg University.

- Die erste Landesvermessung des Kurstaates Sachsen Auf Befehl Des Kurfürsten Christian I. ausgeführt von Matthias Oeder (1586-1607). Zum 800Jährigen Regierungs-Jubiläum Des Hauses Wettin, Dresden 1889, map 13.

- Leipzig, in: Braun, Georg, Hogenberg, Frans, Civitates Orbis Terrarum (5), Cologne 1618, fol. 17v; Heidelberg University.

- Saftleven, Herman, Markt op de Mariaplaats te Utrecht, 1619 – 1685; Rijksmuseum Amsterdam.

- van Doetechum, Johannes of Lucas, Gezicht op velden en huizen langs een landweg, 1559 – 1561; Rijksmuseum Amsterdam.

- Halle, in: Braun, Georg, Hogenberg, Frans, Civitates Orbis Terrarum (5), Cologne 1599, fol. 48v; Heidelberg University.

- Hohndorff, Friedrich, Das Saltz-Werck zu Halle in Sachsen befindlich, Halle 1670, pp. 58-59; University and State Library of Saxony-Anhalt.

- Die Reisen des Samuel Kiechel aus drei Handschriften, K. D. Haszler (ed.), Stuttgart 1866, pp. 4-5; Bayerische Staatsbibliothek. ↩︎

- Wintzenberger, Daniel, Ein naw Reyse Büchlein von der Stad Dreßden aus durch gantz Deudschlandt in die andern anstossenden Königreichen und umbligenden Lendern, Dresden 1578. ↩︎

- The Schmalkaldic War (1546-1547) was a military conflict between the forces of the Catholic Emperor Charles V and a defensive alliance of Protestant princes (Schmalkaldic League) of the Empire. The Protestant princes had formed the League in defence against the increasing power of the Catholic Habsburg dynasty. The war ended with the defeat of the Schmalkaldic League in 1547. ↩︎

- The Thalsaline – Halle and salt around 1700, Francke Foundations. ↩︎