“We arrived in the afternoon in Kiel, the most prominent city in Holstein, where Duke Adolf had his palace built near an arm of the sea. At the time, this arm was frozen, and the ice was thick enough for our coachman to drive across.”1

From Hamburg to Kiel

11 January – 25 January 1586

What is a good time of year to travel in Scandinavia? Today, the time of year is not particularly important. Equipment suitable for all seasons and temperatures is available for the adventurous traveller. However, in the sixteenth century, the cold and snow discouraged most people from undertaking a journey to northern Europe. Not so Samuel Kiechel. After returning to Hamburg from his visit to England and the Low Countries, he set out in January 1586 towards Denmark and Sweden.

Travelling North

Samuel Kiechel spent a day in Hamburg to recover from his exhausting journey through frozen and snow-covered north-western Germany. The next part of his adventure would take him from Hamburg through Denmark to Copenhagen and then to Stockholm. He would spend some time in Stockholm before returning via Kalmar and Malmö to Copenhagen.

After his experiences in the Low Countries and the Rhineland, visiting Scandinavia in 1586 was comparatively safe. Politically, Denmark was joined in a personal union with Norway, meaning that a single monarch ruled both kingdoms. The origin of this union dates back to 1397 (Kalmar Union), and initially, Sweden was also part of it. However, Danish dominance caused dissatisfaction among the Swedish nobility and led to various uprisings. After a massacre of leading Swedish noblemen in 1520, known as the Stockholm Bloodbath, Gustav Vasa, the son of one of those executed noblemen, successfully gained support for a new rebellion. The Swedish nobility elected him as their king (1496-1560), and he also enjoyed broad popular support. The Swedes captured Stockholm and other strongholds in Sweden from the Danes.

Meanwhile, in Denmark, King Christian II (1481-1559) became unpopular with the Danish nobility after initiating reforms that reduced their privileges. They deposed him in 1523 and elected his uncle as the new king. Frederick I (1471-1533) negotiated a settlement with Sweden, resulting in the Treaty of Malmö (1524), which recognised Sweden’s independence. In return, the southern Swedish provinces of Blekinge and Scania remained under Danish control.

Tensions between the two countries continued and erupted again during the Northern Seven Years’ War (1563-1570). Sweden fought against a coalition comprising Denmark, Poland-Lithuania and Lübeck. The conflict concluded with few concessions, ending when both Denmark and Sweden had exhausted their resources.

Battle of Bornholm (1563) between Danish and Swedish ships

At the time of Samuel Kiechel’s visit, both countries were at peace. Sweden, although small and with a low population density, was on the rise and would dominate northeastern Europe in the seventeenth century. A professionalised, modern army and an effective, high-tax system enabled the Swedish kings to successfully engage in wars and conquests around the Baltic until the defeat of Charles XII at Poltava (Ukraine) in the Great Northern War (1700–1721).

However, in 1586, Denmark was still the dominant Scandinavian power. Besides the union with Norway and possession of the two southern Swedish provinces of Scania and Blekinge, the Duchy of Schleswig was also part of the Kingdom of Denmark, and the Danish king was the Duke of Holstein. Although Schleswig-Holstein is now a federal state of modern Germany, until the nineteenth century, Schleswig was part of Denmark, and Holstein belonged to the Holy Roman Empire. The complicated arrangement in the early modern period was a consequence of the Treaty of Ribe (1460). With the treaty, the Danish King became Duke of Schleswig and Count of Holstein (Duchy of Holstein from 1474). In return, the knights and nobility in both realms received far-ranging privileges, and Holstein was guaranteed to remain part of the Empire. Schleswig, as it was politically and socially closely linked with Holstein, received a special status within the Kingdom of Denmark, with the King as the Duke of Schleswig becoming his own vassal.

Travelling first through Holstein, Samuel Kiechel will visit Lübeck and Kiel and then continue to the Duchy of Schleswig and Denmark.

To Lübeck

Samuel Kiechel left Hamburg on 12 January in a sledge pulled by three horses, accompanied by the driver and nine other passengers. Other vehicles had already carved a track into the snow on the road, and Kiechel’s sledge made good progress. That evening, it arrived in the village of Höltenklinken, where the travellers stayed overnight.

The next morning, the sledge and its passengers travelled along a frozen, very slippery road. Whenever there was a slight incline, the sledge drifted to the side. Within an hour, it had overturned twice. Despite these difficulties, the sledge and passengers reached Lübeck at lunchtime.

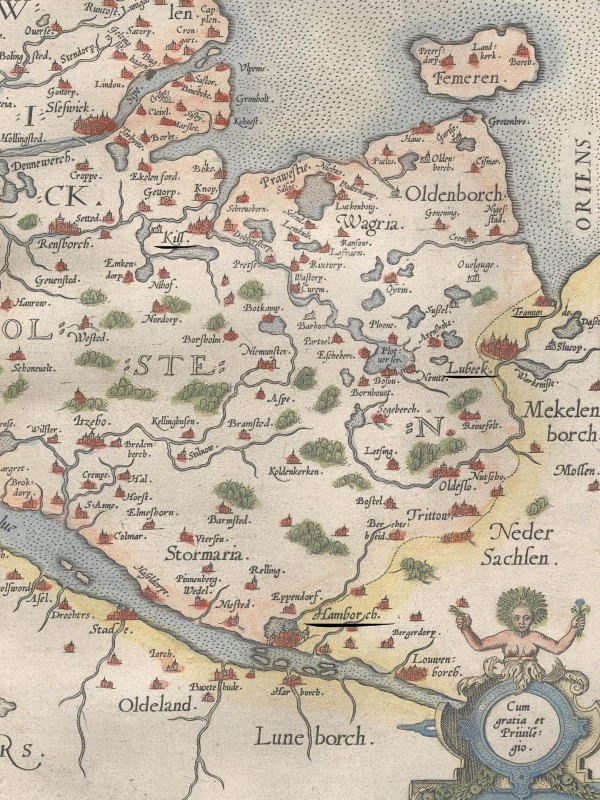

Map of Holstein and the locations Samuel Kiechel visited

Kiechel wrote: Lübeck was a powerful, well-built and fortified city. It served as the seat of a bishop and was a free and imperial city of the Empire. Lübeck was also a significant economic centre, with trade links to Denmark, Sweden, Gdansk and Livonia. Ships regularly sailed to Spain, Portugal and other distant locations each year.

The profile view of Lübeck in the “Civitates Orbis Terrarum” shows the city from the east. Lübeck is depicted as fortified and surrounded by water. Numerous churches dominate the skyline, drawn slightly larger than the surrounding houses. The names of the churches are annotated on the map. On the right side (northeast), there are three large ships and what appears to be the open sea. Although this roughly indicates the direction of Travemünde, Lübeck’s harbour on the Baltic Sea, the actual distance is greater than depicted. The ships and open sea may have been included to emphasise Lübeck’s status as a powerful and wealthy trading port.

Lübeck, 1588

According to Kiechel, Lübeck was also a naval power and had participated in the war between Denmark and Sweden. This conflict was the Northern Seven Years’ War (1563-1570). Lübeck, which had its trade privileges revoked by Sweden and was concerned about obstacles to trade with Russia, joined the war on Denmark’s side. The city’s ships, in alliance with a Danish fleet, initially achieved success against Sweden.

Lübeck, “Queen of the Hanseatic League”

Historically, Lübeck is renowned as one of the founding cities of the Hanseatic League. This powerful medieval trade network linked cities and merchant communities across northern Europe. Established in the thirteenth century, the Hanseatic League dominated trade in the Baltic and North Seas for two centuries. Lübeck was the most prominent city in the Baltic region and played a pivotal role in the lucrative herring trade.

Herring was a vital part of the human diet, especially during Christian feast periods. It was seasonally caught in large quantities around Scania and salted for preservation. The salt was sourced from another core city of the League, Lüneburg. Samuel Kiechel had visited Lüneburg and observed the salt production process.

Herring is packed in barrels for transport

The salted herring was then exported across northern Europe by Hanseatic ships. The herring trade was highly profitable for the cities of the Hanseatic League. It was the foundation of Lübeck’s prosperity. The city’s merchants expanded their trade to Norway, Gotland and the eastern Baltic Shores. Soon, trading posts were established in numerous locations, reaching as far as Novgorod and Smolensk in Russia. The illustration of Lübeck in the “Civitates Orbis Terrarum” reflects the city’s wealth and success.

With economic strength came political influence, enabling the League to secure advantageous agreements and privileges for its cities and merchants across the North and Baltic Seas. They also involved themselves in regional military conflicts when such conflicts threatened their profits and privileges.

However, the League was more of a loose confederation than a unified block, thriving as long as the interests of its member-cities aligned. The fifteenth century marked the beginning of its gradual decline. The trend towards political centralisation and territorial consolidation in Europe led to smaller Hanseatic cities losing their independence, and the League’s privileges diminished. The discovery of sea routes to Asia and America shifted trade towards Western Europe and Atlantic economic centres. Competition on the Baltic increased, threatening the League’s monopoly. English merchant adventurers sought to gain access to the Russian trade, while the Dutch emerged as successful competitors with their new, superior merchant ship — the Fluyt.

By Samuel Kiechel’s time, the Hanseatic League had largely faded. Trading hubs like Hamburg and Lübeck retained some privileges and remained regional powers. Lübeck’s involvement in the Swedish War of Liberation (1521-23) and the Northern Seven Years’ War (1563-70) demonstrated its continued influence and capacity to command substantial naval forces. Nonetheless, it could no longer depend on the support of other Hanseatic cities.

Travemünde

Samuel Kiechel made a day trip to the harbour of Lübeck. He wrote that it was situated two miles outside the city and was called Travemünde. A ‘blockhaus’, a fortified wooden house, guarded the harbour’s entrance. Kiechel also observed the lighthouse. He explained that during the night, the lighthouse’s light guided ships out at sea to the harbour. Large ships had to anchor in Travemünde and could not enter the Trave River, which links the harbour to Lübeck. A drawing from 1604 depicts Travemünde, featuring the lighthouse and the fortified wooden ‘Blockhaus’.

Travemünde, 1604

Justice in Lübeck

Moreover, Kiechel noted that Lübeck had a strict justice system that made no distinction between the rich and the poor. He explained that, around the time of his visit, a nobleman from Holstein named Ranzau had stabbed a peasant and nearly killed him. The nobleman, who came from one of the most influential families in the region, was nevertheless arrested and imprisoned. If the peasant had died within fourteen days of the incident, the nobleman would have faced execution.

The Rantzau family was an old, influential dynasty. At the time of Kiechel’s visit, Heinrich Rantzau (1526-1598) served as governor for the Danish king in Schleswig and Holstein. While Lübeck was part of the Duchy of Holstein, it was a free city, and its capacity to arrest and convict a high-ranking noble from a powerful family was a symbol of its freedom and independence.

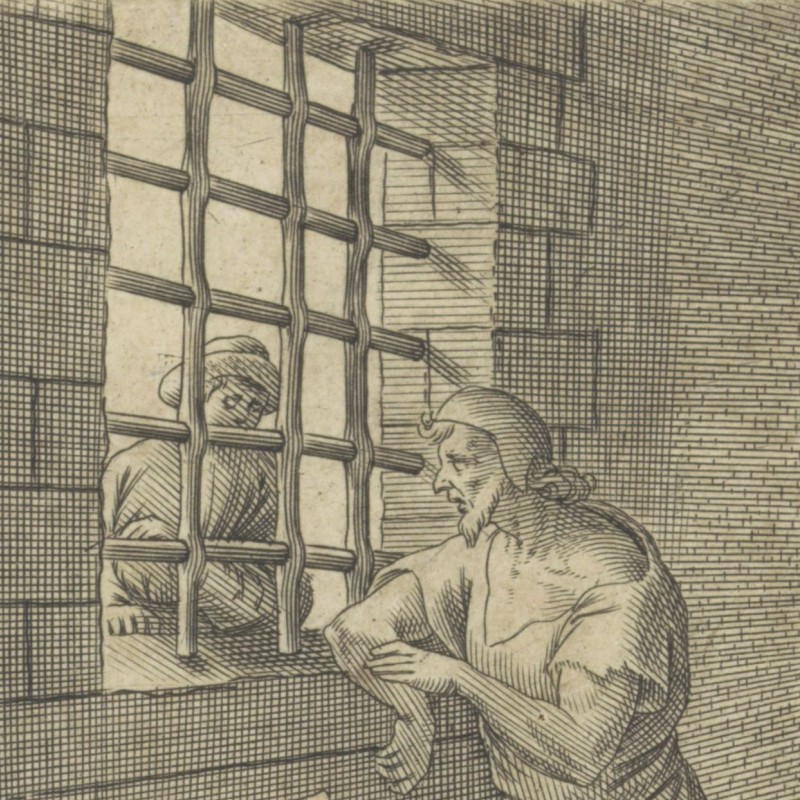

The same strict judicial process applied to Lübeck’s citizens concerning debts and financial claims. When a foreigner sued a citizen for a debt, the accused was required to pay within a few days or provide a form of payment guarantee. If the citizen could not settle the debt, the bailiff (German: Büttel, an old-fashioned term for a court officer) would be sent. During court proceedings, the bailiff was present in the town hall and would then escort the citizen to the ‘böteley’ (house of the bailiff/jail). There, other individuals with similar court verdicts were also held.

Kiechel comments that Lübeck’s bailiff was not publicly shunned as he would have been in his hometown of Ulm. He socialised with guilds or attended social occasions, sitting at the same table as ‘honest men ’ (‘erlichen leüthen’).2 This term refers to a facet of medieval and early modern life, specifically to individuals of social standing and respectable professions. Certain jobs, such as executioners or bailiffs, were necessary but considered to lack honour or social prestige. People fulfilling these roles were publicly shunned and excluded from social events.

However, Kiechel continued, the bailiff had his own drinking vessel. Sometimes, a group of citizens would also visit the bailiff to drink and socialise. The bailiff would serve them beer. According to Kiechel, this behaviour would be out of place in his hometown. But our traveller concludes that this was simply due to local differences.

To Kiel

Our traveller had to stay in Lübeck for nine days. He encountered difficulties in finding new companions to travel north. He eventually left the city on 24 January in a carriage, accompanied by a horse trader, a merchant from Hamburg and a Dane. They arrived in the evening at a village called Rotmansdorf in the county of Holstein.

The group continued their journey the following day and reached Kiel in the afternoon. Our traveller described Kiel as the most distinguished city in the Duchy of Holstein. Duke Adolf (Adolf I of Schleswig-Holstein-Gottorf, 1526-1586) resided there, and his castle was situated near an inlet from the sea (Kieler Förde). The inlet was frozen at the time of Kiechel’s visit. Sledges traversed the ice, and the driver of Kiechel’s carriage did the same.

The duke Kiechel mentioned was Duke Adolf of Schleswig-Holstein-Gottorp (1526–1586). He was the son of King Frederick I (1471-1533) of Denmark and half-brother of Christian III (1503-1559), Frederick’s successor. Both had another brother, John the Elder (1521-1580). In 1544, when Adolf and John had come of age, the three brothers negotiated the partition of Schleswig and Holstein among themselves. John became Duke of Schleswig-Holstein-Haderslev, and Adolf received the new Duchy of Schleswig-Holstein-Gottorp.

Kiel, 1588

A profile view of Kiel appears in volume four of the “Civitates”. The view shows the city from the southwest. On the right side of the image is the Kieler Förde and the harbour area. The castle, Kiechel mentioned, is located in the upper right corner of the city.

On the day of Kiechel’s arrival, a fair was held in Kiel. Many noblemen had come for the occasion. Our traveller observed that the noblemen presented themselves with great pageantry and sought to outdo one another. During the fair, large sums of money changed hands between them. Noblemen lent each other money and claimed debts or deeds. If a nobleman was unwilling or unable to return a favour or repay his debt, it was customary to host a feast at his expense.

Samuel Kiechel did not want to spend a night in the city because noblemen and knights had occupied all the inns. When the noblemen were drunk, they would regard everyone else as little more than animals. Kiechel mentioned hearing of a nobleman who traded his servant for a dog. Luckily, our traveller quickly found new companions and was able to continue his journey without delay.

Illustrations & References

All images are in order of appearance with links to sources on external websites:

- Kiel, in: Braun, Georg, Hogenberg Frans: Civitates Orbis Terrarum (4), Cologne 1594, fol. 34v; Heidelberg University.

- Ens, Gaspar, Rerum Danicarum Friderico II. inclitae memoriae, rerum potiente, terra marique gestarum historia, 1593, pp. 122f; Bayerische Staatsbibliothek.

- Ortelius, Abraham, Theater of the World, Antwerp 1587, fol. 49v; Library of Congress.

- Lübeck, in: Braun, Georg, Hogenberg Frans: Civitates Orbis Terrarum (1), Cologne 1593, fol. 24v; Heidelberg University.

- Visscher, Claes Jansz., Haring pakken en roken bij de Haringpakkerstoren, 1608; Rijksmuseum Amsterdam.

- Anonymous, Der Port oder Haff vor Lübeck sampt dem Blockhauß, 1604; Wikimedia Commons.

- Anonymous, Onbarmhartige dienaar naar de gevangenis gebracht, 1585; Rijksmuseum Amsterdam.

- Bolswert, Boëtius Adamsz., Rijk gekleed gezelschap aan maaltijd bedreigt arme boer in zijn woning, 1610; Rijksmuseum Amsterdam.

- Die Reisen des Samuel Kiechel aus drei Handschriften, K. D. Haszler (ed.), Stuttgart 1866, p. 51; Bayerische Staatsbibliothek. ↩︎

- Ibid., p. 51. ↩︎