“When we were about one mile from Cologne, the inhabitants of a Hamlet told us that Schenck’s mercenaries from Neuss had passed through this place; they were about 40 men on horses and raided the land around Cologne. We were worried about falling into their hands should we fail to reach the city by nightfall.“1

From Aachen to Cologne

14 December – 25 December 1585

The thick walls of Cologne offered a welcome refuge to the traveller who had just crossed the war-torn Low Countries, only to find himself in the war-torn Rhineland. The ancient city provided some respite and, given the time of year, a place to warm himself again. Christmas was approaching, but our traveller had to think about new companions and the journey back to Hamburg.

Aachen (Aken), Cologne (Coelen) and Neuss (Nuys)

Approaching Cologne

Samuel Kiechel and his companions left Aachen on the morning of 14 December along a cobbled road. They spent the next night in a small hamlet in the Duchy of Jülich. At lunchtime the following day, they rode past the fortress of Kerpen. Kiechel noted that the fortress was situated within the borders of the Holy Roman Empire but belonged to the King of Spain, with Spanish soldiers garrisoned there.

The fortress commander sent a soldier to question the travellers about their destination and where they had come from. After this exchange, the group continued their journey. They did not pause for a break because the area was unsafe, and they saw many deserted villages.

Kerpen, 1587

Kiechel wrote that when he and his companions were about one mile outside of Cologne, they passed through a small settlement. Its inhabitants warned the travellers that Schenck’s mercenaries had come from Neuss and passed through the area in the morning. Worried that the mercenaries might attack them if they did not reach the safety of Cologne by nightfall, the travellers spurred their horses and hurried on. Kiechel remarked that they were in such a fearful haste that everyone just charged ahead, and none of them looked out for their companions. But they arrived safely in Cologne in the evening.

The Cologne War

Although Cologne and the surrounding countryside lay outside the conflict zone of the Eighty Years’ War, the Cologne War (Truchsessischer Krieg, 1583-88) had devastated the area. The war began when Gebhard Truchsess von Waldburg (1547-1601), Archbishop and Prince-Elector of Cologne, converted to Protestantism but did not resign from his position. Instead, he aimed to transform the ecclesiastical principality into a secular duchy. This move would not only have regional consequences but also alter the balance of power within the Holy Roman Empire. The Prince-Elector of Cologne was one of the seven electors responsible for selecting a new Emperor. With the prospect of Cologne becoming a secular Protestant territory, the power balance would shift away from the Catholic faction, possibly enabling the next Emperor to be a Protestant. Due to the dynastic ties of the Habsburgs, Spanish troops became involved in the conflict on the side of the Catholic faction, and the Cologne War developed into a protracted struggle that left the land devastated and deserted.

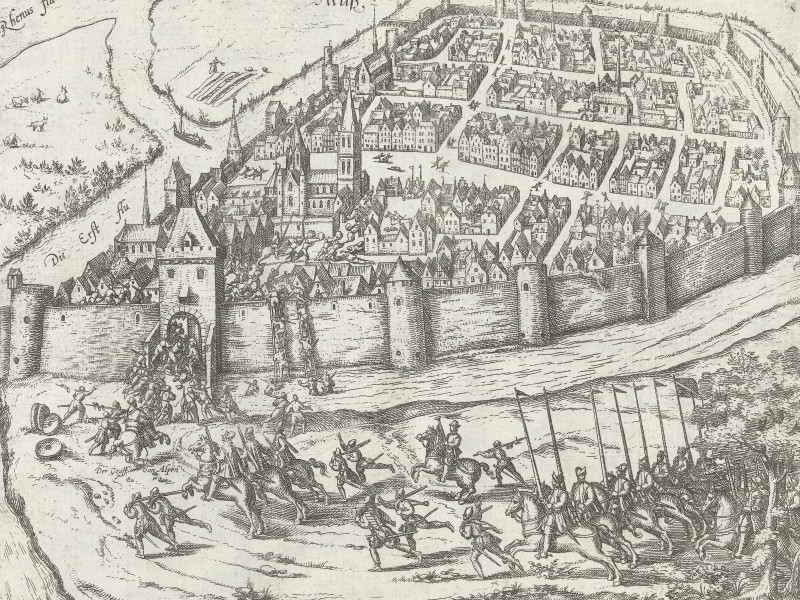

Siege of Neuss, 1585

Schenck’s mercenaries, mentioned by Kiechel, were a troop of soldiers led by Martin Schenk von Nideggen (c. 1540-1589). Schenk was a mercenary commander who fought for both the Spanish and Dutch in the Eighty Years’ War, as well as for Gebhard Truchsess von Waldburg during the Cologne War. He was regarded as a capable and often successful leader, though also ruthless, having been responsible for the ransacking of several towns in the Rhineland. Kiechel noted that these mercenaries had come from Neuss. An army supporting Gebhard von Waldburg had seized Neuss in May 1585, and the town subsequently served as a base for raids of the surrounding lands all the way to Cologne.

In Sixteenth-Century Cologne

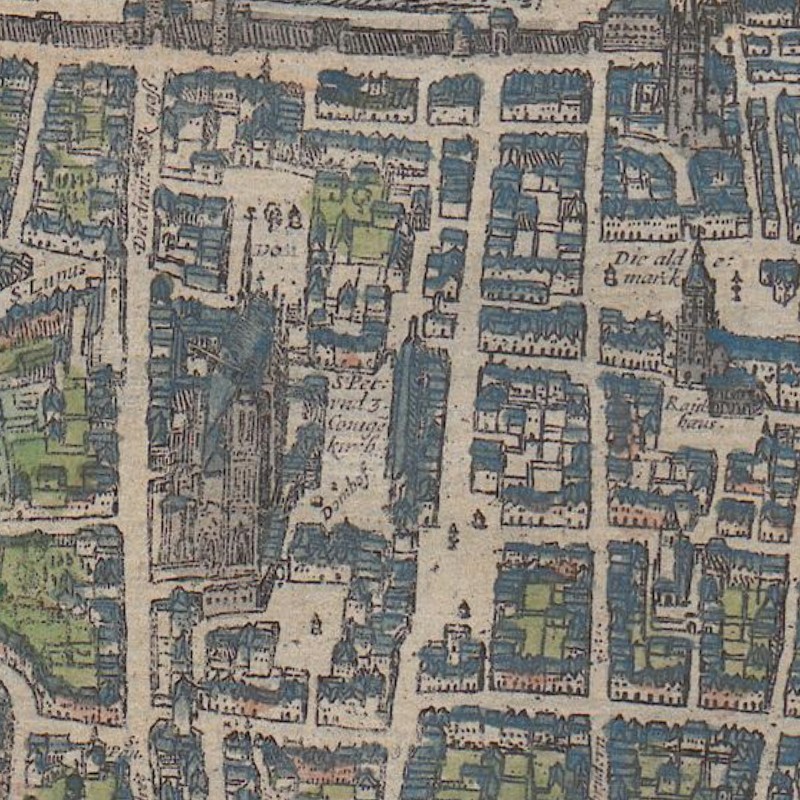

Samuel Kiechel described Cologne as a large, fortified, densely populated city with many Dutch migrants who had fled the conflict in the Netherlands. The city was longer than it was wide. Much trade was taking place due to Cologne’s location on the Rhine River. The city’s houses were tall, large, solid and built of stone. Kiechel heard that the city of Cologne had as many churches as there were days in the year.

For many migrants fleeing the Eighty Years’ War in the Netherlands, Cologne had become their new home. Among them was Frans Hogenberg, the engraver and publisher of the “Civitates Orbis Terrarum”, who had been born in Mechelen and lived in Antwerp before he fled. Cologne was also the hometown of Georg Braun, Hogenberg’s co-publisher. It is therefore not surprising that an impressive and detailed map of the city is found in volume one of the “Civitates”.

Cologne, 1572

The print shows Cologne from the west, with the Rhine River in the background. The city has a semicircular shape. Outside the walls, as well as inside, there are many fields and orchards. Cologne is portrayed as a vast and densely populated city. In the sixteenth century, it had a population of around 40.000 inhabitants. The harbour on the Rhine is busy with many ships.

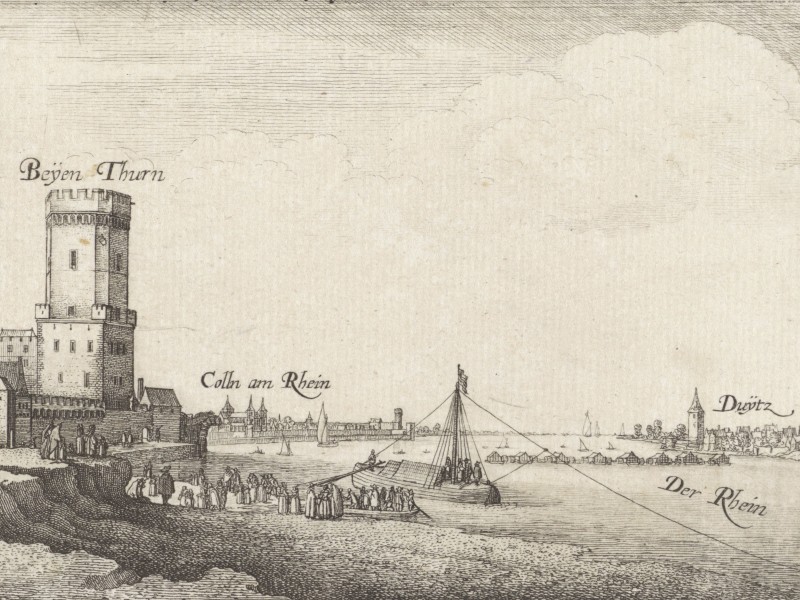

Harbour area of Cologne

Cologne is one of the oldest cities in Germany. Founded in 50 AD by the Romans, its location on the Rhine River gave it strategic importance and made it an economic centre that survived the fall of the Roman Empire and the turbulent early Middle Ages. The city became the seat of an archdiocese and an ecclesiastical principality, with its archbishop being one of the seven Prince-Electors who would elect the German King and thereby the next Holy Roman Emperor. Cologne was also a member of the Hanseatic League and had extensive trade connections with England.

Cologne, ca. 1627 – 1636

This dual role as the seat of an archdiocese and a large, powerful city seeking autonomy, like other cities achieved in the Middle Ages, led to lengthy political and sometimes violent confrontations between the archbishop and Cologne’s citizens. In 1288, during the regional power struggle known as the War of the Limburg Succession (1283-1289), the archbishop and his allies were defeated in battle by an alliance of regional lords and citizens from Cologne. Consequently, the bishop was forced to recognise the de facto autonomy of the city, and he and his successors took up residence in Bonn. Nevertheless, it took until 1475 for the Emperor to formally recognise Cologne as a free and imperial city. Despite gaining independence from the archbishop, Cologne did not, unlike many other places in northern Germany, become Protestant in the sixteenth century.

Samuel Kiechel’s visit to Cologne was during a troublesome time for the city. The previously mentioned Cologne War had devastated the region, and the Eighty Years’ War brought economic hardship. Regional trade with the Low Countries had become dangerous and challenging. Kiechel had witnessed the dangers merchants faced when travelling to cities in the Spanish Netherlands. Cologne’s international trade, especially its valuable connection to England, became perilous because the city’s main access to the sea, the Rhine River, also passed through the conflict zone. Dutch fleets operated on the river, making traffic hazardous and difficult to navigate. Our traveller noted that the Rhine was blockaded when he visited Bremen five months earlier. He wrote that all goods destined for Cologne and the surrounding area had to be transported overland via Bremen, which was likely a slow and costly process.

Cologne Cathedral

Despite these difficulties, Cologne remained the most populous city in the Empire and was worth visiting. Its main attraction was, and still is, its cathedral. Our traveller visited the cathedral and was impressed by its size. However, he regarded the interior as rather plain, noting that the walls were neither plastered nor whitewashed. In Kiechel’s view, the building might just as well be a trading house or stock exchange, as even during Mass, many hundreds of people wandered inside.

Cologne Cathedral

Samuel Kiechel’s somewhat disapproving opinion of Cologne Cathedral may partly stem from his Protestant perspective. His comment that the cathedral resembled a trading house could be a reference to the story of Jesus expelling merchants from the temple in Jerusalem. Alternatively, it might reflect a sense of local pride and rivalry. In Kiechel’s hometown of Ulm stood the Ulm Minster, an equally impressive church. The construction of both churches had not been completed by the sixteenth century, with the steeples still unfinished. Today, Ulm Minster is the world’s tallest church, while Cologne Cathedral ranks third.

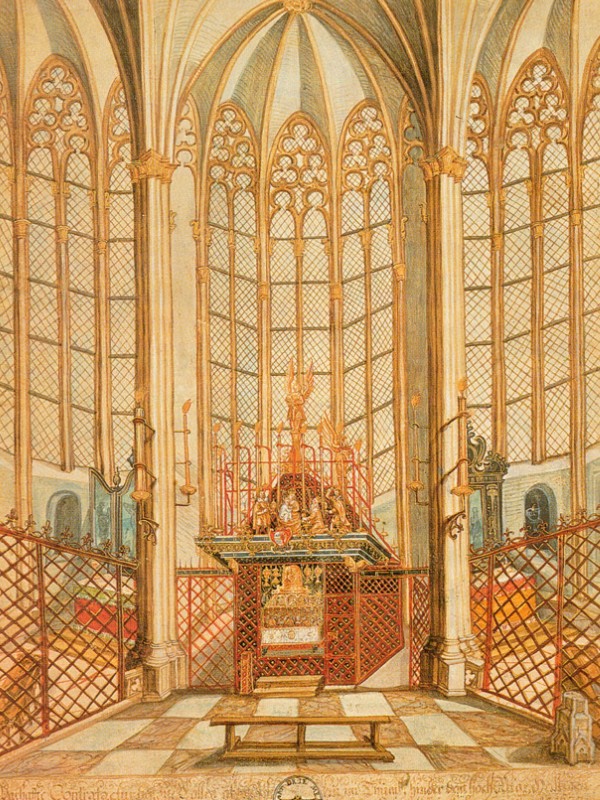

The cathedral housed a famous reliquary, the Shrine of the Three Kings. The Three Kings had visited Jesus after his birth with gifts of gold, frankincense and myrrh. Their remains had been kept in Milan until Emperor Frederick Barbarossa conquered the city in 1162, when the relic was taken and transferred to Cologne.

The Shrine of the Three Kings attracted pilgrims and visitors alike. Samuel Kiechel was shown to an altar behind the choir. The altar was surrounded by arches and secured with iron bars. Behind the bars stood what looked to our traveller like a coffin or box, and he heard that it was the Shrine of the Three Kings. Candles and lamps around this box were always burning, and valuable jewellery and silver dishes had been placed all around it.

Shrine of the Three Kings in Cologne Cathedral, 1633

Kiechel was somewhat sceptical. He wrote that the bones were supposed to be in the shrine. Most likely, this was because, while the shrine had always been on display in the cathedral, it was not opened until the nineteenth century.

Preparations

Samuel Kiechel spent several days in Cologne to rest. The group he arrived with went their separate ways, and he looked for new companions. Kiechel wanted to travel through Westphalia to Münster and then return via Bremen to Hamburg. Eventually, he joined a group of Cologne merchants trading in wine, cheese, butter and herring who were heading in that direction.

Before the journey, Kiechel had to sell his horse. He mentioned that he had bought the animal in Antwerp and intended to keep it, but was advised against it. It was late December, and the temperature was so cold that the Rhine was frozen. To Kiechel, it appeared as if the ice was solid enough to support a horse, but his new companions disagreed. They argued that travelling on horseback was too difficult due to the snow-covered roads. The group would travel on foot, and so would Kiechel. Nevertheless, he was now under pressure to sell the animal quickly and regretted doing so at a loss.

On 25 December, Christmas Day, Samuel Kiechel and his new companions left Cologne and crossed the frozen Rhine.

It might be strange to us that our traveller did not mention that it was Christmas. Today, Christmas in Cologne, like in most German cities, is a time of Christmas markets with stalls offering a variety of food, mulled wine and seasonal delicacies. It would be the time of Christmas shopping, decorated streets and houses. However, most of these traditions are modern additions. In the Middle Ages and early modern period, Christmas was primarily a religious festival, subordinate to Easter, the high point of the Christian calendar, which celebrated the resurrection of Christ.

Samuel Kiechel does not mention any celebrations. The reason may be a difference in the calendar. Cologne had remained Catholic after the Reformation and adopted the new Gregorian calendar in 1583, along with other Catholic territories. However, our Protestant traveller still used the old Julian Calendar. Therefore, while it was Christmas Day for Kiechel, it was 4 January 1586 for the citizens of Cologne.

Illustrations & References

All images are in order of appearance with links to sources on external websites:

- van de Velde, Esaias, Struikrovers of soldaten bij een drenkplaats, 1630; Rijksmuseum Amsterdam.

- Ortelius, Abraham, Theater of the World, Antwerp 1587, fol. 30v; Library of Congress.

- Hogenberg, Frans, Kaart van Kerpen en Lommersum, 1587; Rijksmuseum Amsterdam.

- Hogenberg, Frans, Inname van Neuss, 1585; Rijksmuseum Amsterdam.

- Cologne, in: Braun, Georg, Hogenberg Frans: Civitates Orbis Terrarum (1), Cologne 1593, fol. 31v; Heidelberg University.

- Hollar, Wenceslaus, Gezicht op een fort aan de Rijn nabij Keulen, 1627 – 1636; Rijksmuseum Amsterdam.

- Wahrhaffte Contrafactur der zue Coellen ahm Rhein im Thumb hinter dem Hochaltar Heiligen drey Königen Begrebnus, deren Größe weiset hie undergesetzter Maßstab gethā in Cöllen dē 1. 8.ber anno 1633; Wikimedia Commons.

- Berchem, Nicolaes Pietersz., IJsgezicht nabij een stad, 1647; Rijksmuseum Amsterdam.

- Die Reisen des Samuel Kiechel aus drei Handschriften, K. D. Haszler (ed.), Stuttgart 1866, p. 43; Bayerische Staatsbibliothek. ↩︎