“ … , we left Brexen and travelled to Berlin. The Elector of Brandenburg has his residence in the city. A river flows through Berlin and divides it into two parts with different names. One part of the city, with the palace of the Elector, is called Cölln an der Spree and the other part is called Berlin.“1

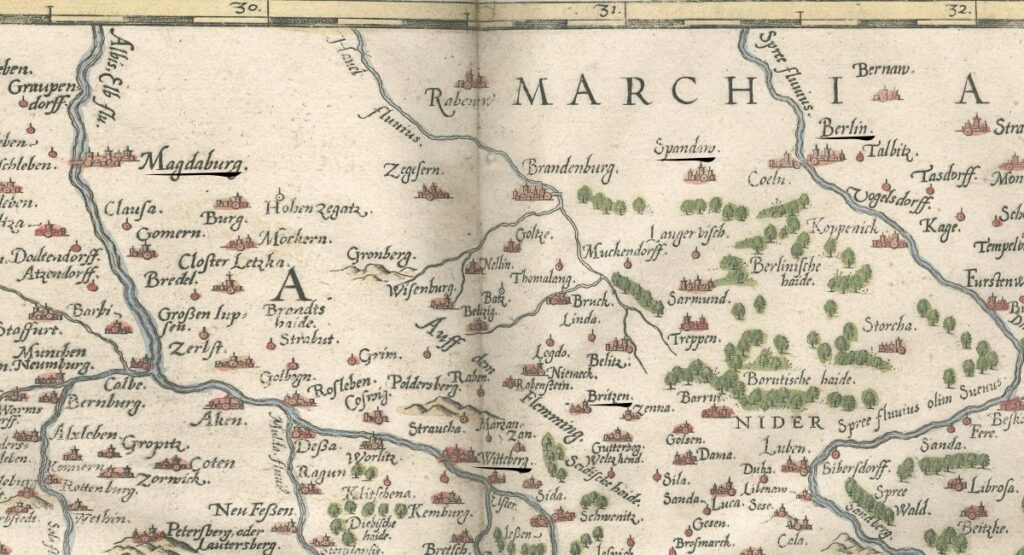

Via Magdeburg to Berlin

20 June – 27 June 1585

Berlin, today the largest German city and a popular tourist destination, was not much more than a large town on the edge of the Empire in the late sixteenth century. For a traveller from an imperial city in southern Germany, the place was not particularly impressive. Then again, at this early stage of Samuel Kiechel’s journey, the observations in his journal remain brief, and it can be difficult to interpret his opinions. But before visiting the future capital, Samuel Kiechel went to Magdeburg, a city of much greater historical significance at the time.

The Road to Magdeburg

Samuel Kiechel stayed in Wittenberg for two days and departed on 20 June to travel via Zerbst to Magdeburg. Zerbst was located in the Principality of Anhalt, roughly halfway between Magdeburg. Our traveller recommended the local beer.

The Principality of Anhalt was one of many minor early modern German states. Kiechel never failed to mention the territories he passed through. Without regulated borders or signposts, he presumably asked his guides or the local people he encountered.

Our traveller spent the night in Zerbst before heading to Magdeburg the following day, arriving at lunchtime. Kiechel’s description of the city was brief: Magdeburg was a powerful and heavily fortified imperial city with an impressive cathedral divided into the old and new towns. The river Elbe flowed close to the city walls.

Visiting Magdeburg

Magdeburg, ca. 1600

Samuel Kiechel had come from the east, and a similar sight of the city must have greeted him. The view across the Elbe depicts Magdeburg not only as a religious centre but also as a commercial hub. While the city’s numerous churches, including the impressive cathedral, attest to Magdeburg’s religious significance, the lively activity along the river, with many boats being loaded and unloaded, underscores its role as a vital commercial hub in the region.

This print offers a rare view of a city that Samuel Kiechel visited, which, fifty years later, no longer existed in this state. The print is dated 1637, but it is older. By 1637, Magdeburg was in ruins. The city and its residents endured great suffering during the Thirty Years’ War (1618–1648). Magdeburg was besieged by imperial troops and captured on 20 May 1631. During the war’s worst massacre, soldiers killed around 20.000 inhabitants and burned the city to the ground. The cathedral was one of the few structures to survive.

Magdeburg, 1572

A bird’s-eye view in the “Civitates Orbis Terrarum” shows Magdeburg from the west. The print contains little additional detail. The Old Town is on the right side (south), and the New Town on the left. Walls and a moat protect both parts. The Elbe River runs past Magdeburg, with a bridge crossing it. The churches are labelled and depicted on a slightly larger scale than other buildings. Magdeburg Cathedral is located on the right side (“Der Dom”).

Magdeburg was an important political and religious centre in medieval Germany. The city was first mentioned in the sources in 805 and gained significance during the reign of Otto I (912–973). Otto, King of East Francia, was crowned Roman Emperor in 962 by Pope John XII. For Otto, who, like most medieval rulers of the time, had no fixed capital but travelled from one imperial palace (“Kaiserpfalz”) or city to the next, Magdeburg became one of his primary residences. He granted the city to his first wife, Eadgyth, granddaughter of Alfred the Great, as dower. Both Eadgyth and Otto were buried in Magdeburg Cathedral.

In the tenth century, the Elbe River was the main border between East Francia, situated on the western bank, and the numerous Slavic tribes to the east. Magdeburg’s strategic location made it a key staging point for missionaries spreading Christianity towards the east. The Archbishopric of Magdeburg was established for this purpose in 968. The Cathedral of Magdeburg is the oldest Gothic cathedral in Germany. It remains a prominent feature of the city’s skyline today. Its construction began in 1209 after the previous church had burned down.

Magdeburg was also home to the “Magdeburg Law”. In the late Middle Ages and early modern period, town laws granted specific rights and freedoms, such as self-governance, economic autonomy, and municipal independence from local lords. However, these privileges were not single, codified laws but loose collections of rules, customs, and legal concepts. Existing town laws were usually granted to newly founded towns or adopted by existing settlements. As a result, some laws, such as the “Lübeck Law” and the “Magdeburg Law,” spread widely across central and Eastern Europe. The “Magdeburg Law” was adopted by cities as far as Tallinn (Estonia), Vilnius (Lithuania), and Kyiv (Ukraine). Nonetheless, cities did not simply copy existing laws; in ambiguous legal cases, they sought guidance on how to interpret the town law from the lay judges of the mother town, in this case, Magdeburg. In this way, Magdeburg played a significant role in the history of many settlements east of the Elbe.2

Returning to Wittenberg

Samuel Kiechel spent one day (22 June) in Magdeburg and hurriedly left the following morning. He had heard that the former superintendent of Augsburg, Georg Mylius, had come to Wittenberg and would give his first sermon on 24 June. Our traveller was eager to return to Wittenberg for this occasion.

Georg Mylius (1548 – 1607)

Georg Mylius (1548 – 1607) was a Protestant theologian from Augsburg. He fled his hometown after the Gregorian calendar reform sparked clashes between the Catholic and Protestant inhabitants of Augsburg. Mylius spent a year in Ulm before moving to Wittenberg in 1585 to take the position of professor of theology at the university. Kiechel had probably heard of Mylius during the theologian’s time in Ulm.

Hearing the news of Mylius’ arrival, Samuel Kiechel decided to return to Wittenberg. He left Magdeburg on 23 June with a messenger and arrived in Zerbst at lunchtime. The messenger was old and struggled to keep up with our traveller. Kiechel left him behind and found another man to guide him to Wittenberg, where they arrived on the same day. Kiechel spent 24 June in Wittenberg. Our traveller attended church to listen to Mylius’ sermon with many other townspeople.

The Calendar Reform

Samuel Kiechel regularly mentioned the date in his journal. However, he did not use it to preface his daily entries. Sometimes, the date is in the middle or at the end of a paragraph. If our traveller did not write down the date, he usually lets the reader keep track of time by referring to a day as ‘the next/following day’ or by stating how many days he had spent in a place.

However, the dating in Kiechel’s journal is not as straightforward as it would seem. At the time of his journey, the Julian calendar had been in use for about 1600 years. While it accurately set the length of a year at 365 days, it was eleven minutes too long compared to the solar year. The error itself was minor, but the minutes had accumulated over time. By the sixteenth century, the Julian calendar was noticeably diverging from the astronomical year.

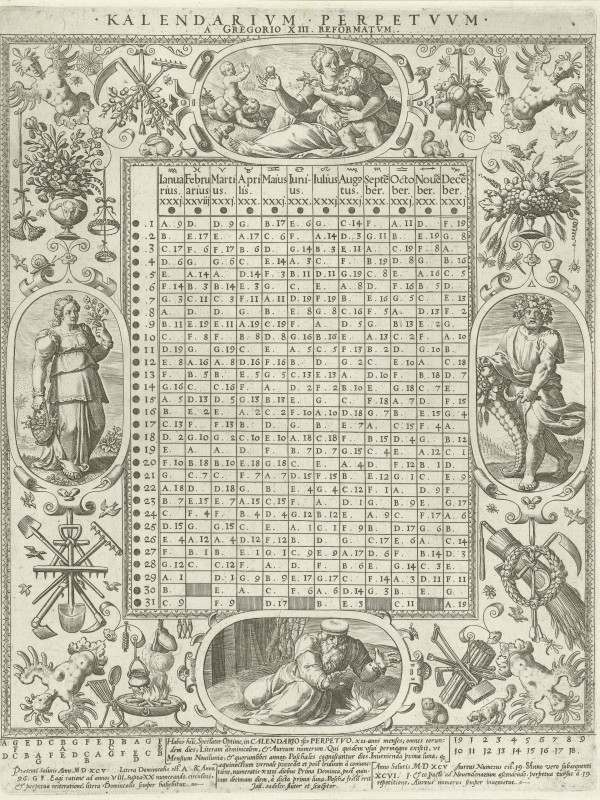

The Gregorian Calendar, 1595

In 1582, Pope Gregory XIII initiated a calendar reform. The new calendar corrected the estimated average length of the year, aligning it more accurately with the astronomical year. The Gregorian calendar was announced through a papal bull and adopted within the Catholic regions of Europe.

However, since a papal decree announced the new calendar, the reform immediately became a subject of religious contention. Protestants refused to adhere to a papal order. For a time, there was concern that the new calendar was a scheme to assert Catholic dominance. The widespread adoption of the new calendar in Protestant and Orthodox territories took considerable time, with some regions only adopting it in the early twentieth century. During these centuries, two calendars were in use across Europe.3

Kiechel began his journey in 1585, three years after the introduction of the Gregorian calendar. He was a Protestant, and his hometown of Ulm did not adopt the new calendar until 1700. Kiechel, therefore, used the old Julian calendar in his journal. He occasionally mentioned that two calendars were in use, but did not go into detail. As he was writing for a contemporary audience, there was probably no need for explanations.

For this project, I used the date I found in Kiechel’s journal (Julian calendar) to avoid errors on my part in calculating the date according to the Gregorian Calendar and to prevent confusion when comparing it to the source.

From Wittenberg to Berlin

On 25 June, Samuel left Wittenberg in the back of a cart headed for Berlin. However, half an hour outside the city, the poor weather turned the road into a mire. The cart got stuck, and the horses could not pull free. Our traveller had to return to Wittenberg to seek another opportunity to continue. Eventually, he found a Polish coachman from Poznań on his way home. The coachman spoke only Polish, and Kiechel knew only German, French and a bit of Latin.

The language barrier between the traveller and his various companions is a recurring theme of the journey. He did not primarily choose his companions based on their cultural background or a common language. A general observation of Samuel Kiechel’s journey is that our traveller was fairly open towards other people and travelled with noblemen and peasants. While he could not ignore the social status of his companions, Kiechel rarely appeared to judge them by it. In the middle of the Empire, he might have eventually found someone who spoke German. However, the Polish coachman was available, and both men agreed to travel together despite barely being able to communicate.

On the way to Berlin, Kiechel and his new companion left the Duchy of Saxony. They passed through the small town of Treuenbrietzen, located in the Margraviate of Brandenburg. The following morning, the two men continued their journey and arrived in Berlin on the same day.

Stopover in Berlin

Kiechel was still not accustomed to keeping a journal, and his description of the city is relatively brief. He wrote: The river Spree divides Berlin into two parts. The Elector of Brandenburg has his court in the city. The part of the city with the palace is called Cölln, and the other part is called Berlin.

Berlin, 1536

The “Civitates Orbis Terrarum” contains no image of Berlin. However, a profile view of the city from the northeast appears in the journal of Otto-Henry. The silhouette features numerous church towers, suggesting a city of considerable size. journal of Otto-Henry.4

Berlin, c. 1650

Berlin gained importance in the fifteenth century when Frederick I (1371 – 1440) became Elector of Brandenburg. Frederick was from the Hohenzollern Dynasty. Berlin became the political centre of the Margraviate of Brandenburg and the residence of the Elector. Members of the Hohenzollern Dynasty would eventually rule the Kingdom of Prussia and the German Empire until 1918.

Despite being the residence of the Elector of Brandenburg, Berlin was, at the time of Kiechel’s visit, of minor political importance and on the periphery of the Empire. Power was centred around the Emperor, and the ruling House of Habsburg had its ancestral lands in the south, in Austria and Switzerland.

Only after the Thirty Years’ War did Berlin become an influential city of European stature. The energetic Elector Frederick William (1620 – 1688) unified his fractured domain and introduced reforms. To restore the badly depopulated and devastated country, Frederick William issued the Edict of Potsdam (1685). The Edict invited Protestants who suffered from religious persecution, especially in France, to resettle in Brandenburg. They were promised land, financial support, exemption from taxes, and other benefits. About 20.000 Huguenots accepted this invitation, many of whom were merchants and artisans. The migrants provided a much-needed economic boost after the devastation of the war. When Frederick William’s son, Frederick (Frederick I, 1657–1713), crowned himself King of Prussia in 1701, Berlin became a European capital.

But at the time of Samuel Kiechel’s visit, this was all in the distant future. Our traveller spent only one night in Berlin and left for Spandau the following day.

Illustrations & References

All images are in order of first appearance with links to sources on external websites:

- Berlin, in: Reisealbum des Pfalzgrafen Ottoheinrich 1536/37; Wikimedia Commons.

- Ortelius, Abraham, Theater of the World, Antwerp 1587, pp. 48-49; Library of Congress.

- van de Velde, Jan, Gezicht op Maagdenburg, 1637; Rijksmuseum Amsterdam.

- Magdeburg, in: Braun, Georg, Hogenberg Frans, Civitates Orbis Terrarum (1), Cologne 1593, fol. 30v; Heidelberg University.

- Anonymous, Image of Georg Mylius, 1584; Herzog August Bibliothek Wolfenbüttel.

- Sadeler, Johann, Kalendrivm Perpetvvm, 1595; Rijksmuseum Amsterdam.

- Anonymous, Landschap met boerenkar, 1606 – 1700; Rijksmuseum Amsterdam.

- Ruyscher, Jan, Ansicht Berlins von Nordwesten (Berlin from the northwest), 1650-1660; Stiftung Preußische Schlösser und Gärten Berlin-Brandenburg.

- Die Reisen des Samuel Kiechel aus drei Handschriften, K. D. Haszler (ed.), Stuttgart 1866, pp. 6-7; Bayerische Staatsbibliothek. ↩︎

- Kümper, Hiram, Magdeburger Recht, in: Online-Lexikon zur Kultur und Geschichte der Deutschen im östlichen Europa, University Oldenburg, 2012. ↩︎

- Hamel, Jürgen: Die Kalenderreform Papst Gregors XIII. von 1582 und ihre Durchsetzung, in: Geburt der Zeit. Eine Geschichte der Bilder und Begriffe. Eine Ausstellung der Staatlichen Museen Kassel vom Dez. 1999 bis 19. März 2000, Wolfratshausen 1999, pp. 292-301. ↩︎

- Pabel, Angelika, Pleticha-Geuder, Eva, Schmid, Anne, Schmidt, Hans-Günther (eds.): Reise, Rast und Augenblick. Mitteleuropäische Stadtansichten aus dem 16. Jahrhundert, Ausstellungsführer, Dettelbach 2002, p. 92f. ↩︎