“Delft is a small, heavily fortified, well-built and pleasant city. It has a beautiful market square, and the people brew superb beer. Not long ago, a Spaniard shot and killed the Prince of Orange. At each gate of the city, a quarter of the assassin’s body was hung.“1

From Delft to Dordrecht

1 August – 2 August 1585

In Delft

Eastern Gate of Delft

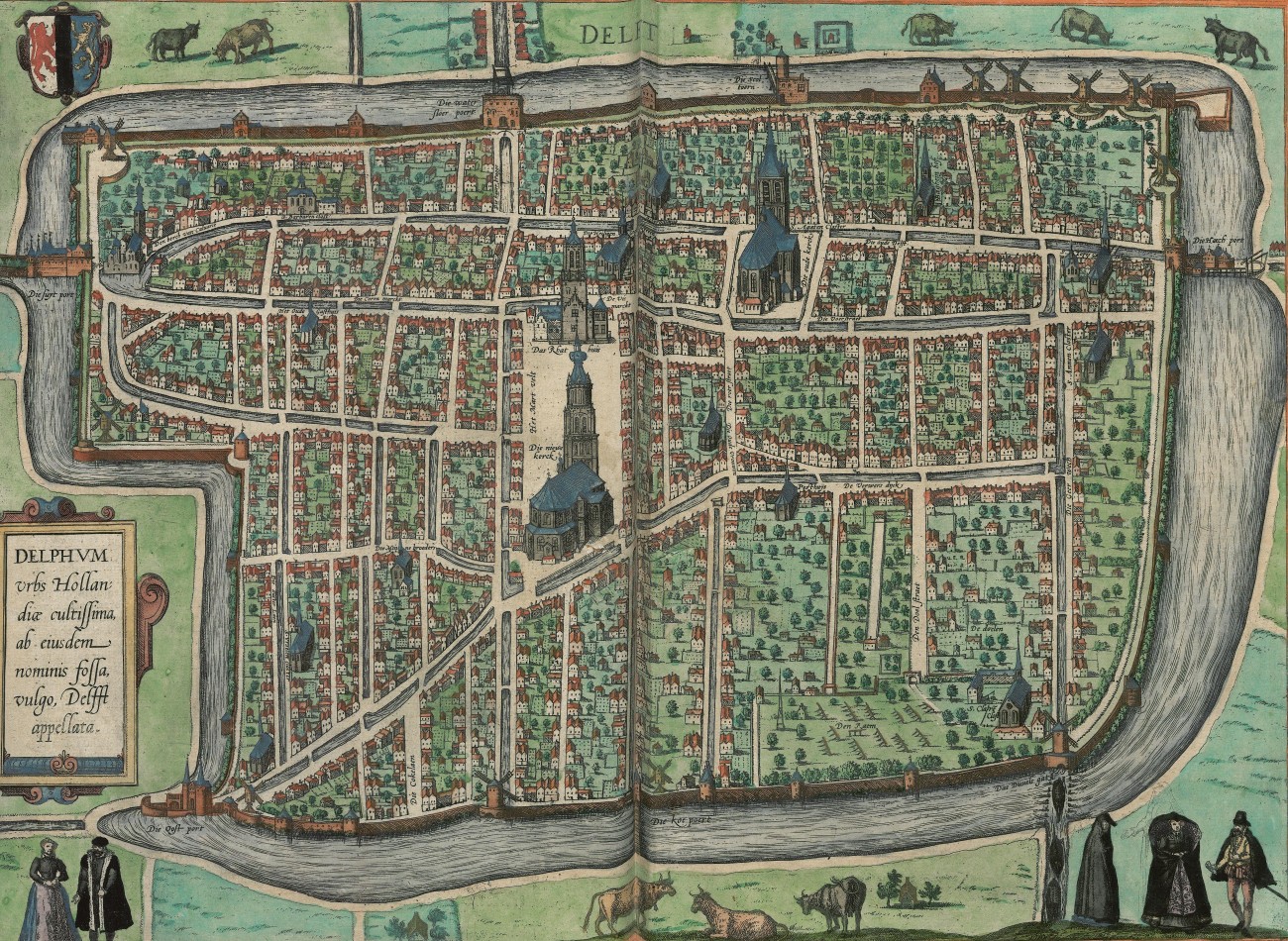

Samuel Kiechel arrived in Delft in the evening. Security in the city was tight, requiring him to state his name at both the gate and the inn. He found Delft to be a small, fortified, well-constructed and pleasant city with a beautiful market.

In this view from the northeast, the market square, the Nieuwe Kerk (New Church), and the town hall are centrally located in Delft. The Oude Kerk (Old Church) is situated on the right side of the square. The three buildings appear larger in scale compared to their surroundings.

Delft, 1581 (1536)

This view is a reproduction of an older woodcut. The open areas on the lower right side of the image are remnants of a fire that devastated the city in 1536, suggesting that this image dates from that time.

More widely known are the paintings of Delft by Johannes Vermeer. He created his “The Little Street” and “View of Delft” roughly seventy-five years after Kiechel visited the city. Delft will have changed in the intervening time, but the paintings still capture an impression of life in the city.

Vermeer’s ‘The Little Street’ in Delft

The Murder of William of Orange

Delft had been the scene of a political assassination just a year before Kiechel’s visit. Our traveller reports that a Spaniard had shot the Prince of Orange. The murderer was captured and executed. Parts of his body were displayed at the four gates of Delft, where Kiechel saw the remains.

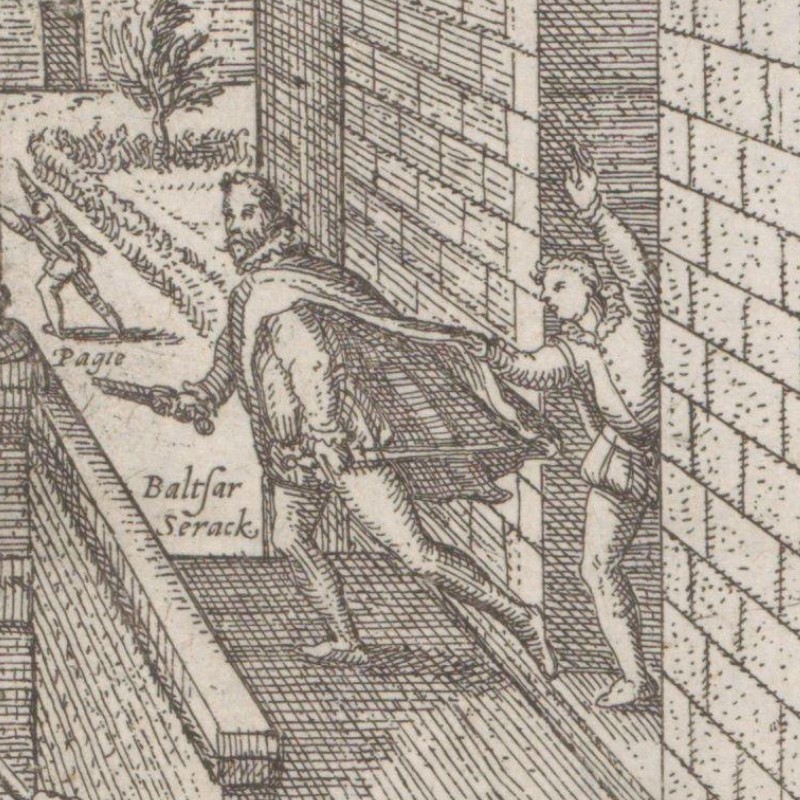

Kiechel refers to the assassination of William of Orange (1533-1584), also known as William the Silent, by Balthasar Gérard on 10 July 1584. William had grown up at the imperial court in Brussels. He was initially loyal to Emperor Charles V and later to Charles’ son, Philip II. Philip appointed him governor (stadtholder) of Holland, Zeeland and Utrecht in 1559. However, over time, William began to share the concerns of many other Dutch noblemen who were gradually excluded from local government in favour of Spanish noblemen.

William of Orange (1533-1584)

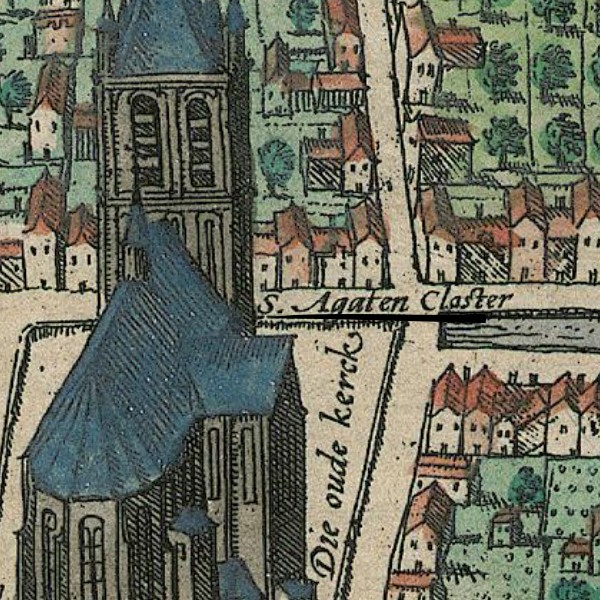

Initially, the protests were requests to redress the balance of power. However, they soon became entangled with religious matters. Although many Dutch noblemen were Catholic, they were nevertheless opposed to the violent persecution of Protestants by the Spanish. Soon, religious questions became the driving force that led to the Dutch Revolt (Eighty Years’ War). William emerged as the leader of the rebellion against the Spanish. In 1579, Philip II outlawed William, and an assassination attempt was made in Antwerp in 1582. Following this attempt, William moved his residence to the former Sint Agathaklooster (St. Agatha monastery) in Delft, subsequently renamed “Prinsenhof”.

The Oude Kerk and St. Agatha monastery

On the map, “S. Agaten Closter” is written beside a few unremarkable houses just behind the Oude Kerk (Old Church). Compared to the two churches and other significant buildings, the monastery is not highlighted as a prominent location because the view was copied from an older image dating around 1536.

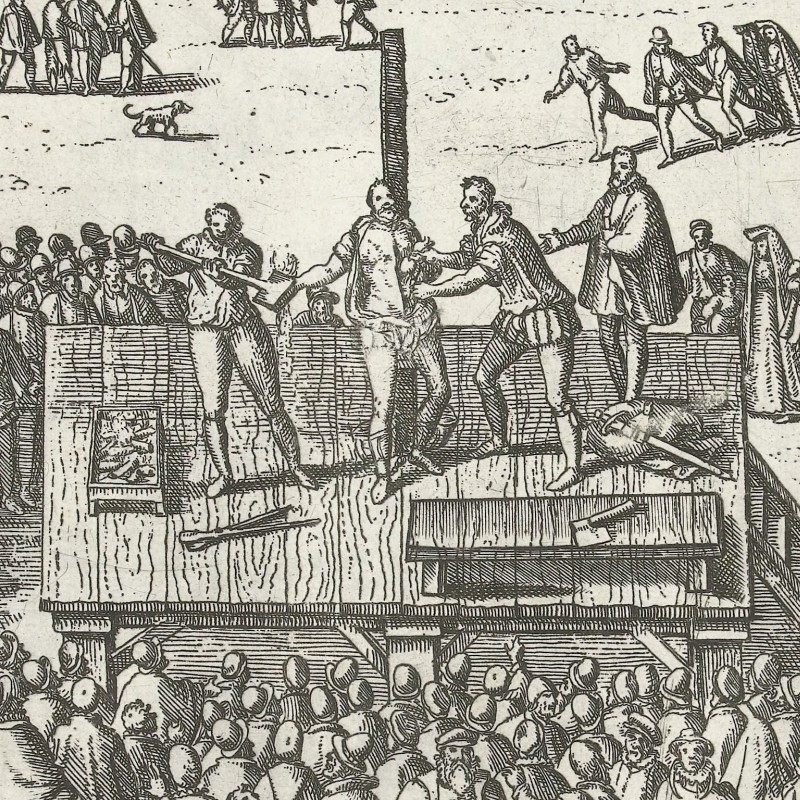

Regarding the murder, Philip II, King of Spain and the Netherlands, had placed a bounty on William of Orange’s head. Balthasar Gérard, a devout Catholic and admirer of Philip, managed to gain access to the Prinsenhof and shot William. After the assassination, Gérard tried to escape but was caught, tortured, and ultimately executed.

The assassination of William the Silent, with the murderer captured, and a scene showing his execution.

Following the successful assassination, Philip did not pay out the promised bounty in money. Instead, Gérard’s parents received three country estates in the Franche-Comté, and he was elevated to the peerage. These three estates had originally belonged to William’s family.

By Boat to Dordrecht

Samuel Kiechel stayed in Delft for one night and left the city the next day with two merchants. The three men made a short journey to Rotterdam and arrived there in time for breakfast. Kiechel noted that Rotterdam was poorly built and mainly inhabited by fishermen.

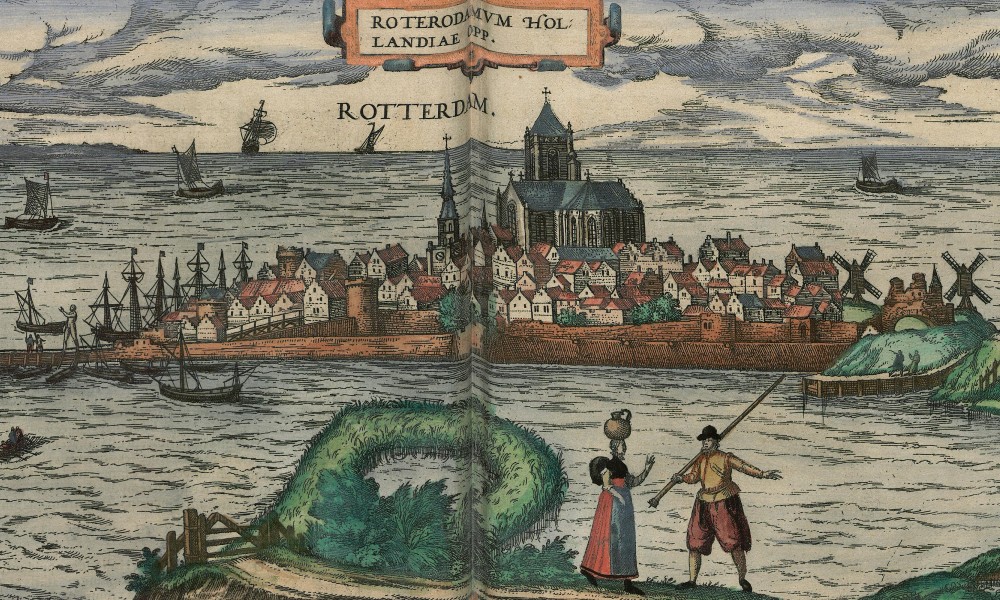

Rotterdam, 1581

The representations of Rotterdam in the “Civitates Orbis Terrarum” include a profile view in volume three and a bird’s-eye view in volume four. The profile view depicts the city as a peninsula stretching into the sea. However, since Rotterdam is neither a peninsula nor situated at the coast, this illustration is probably a copy of an older woodcut and isn’t entirely accurate.

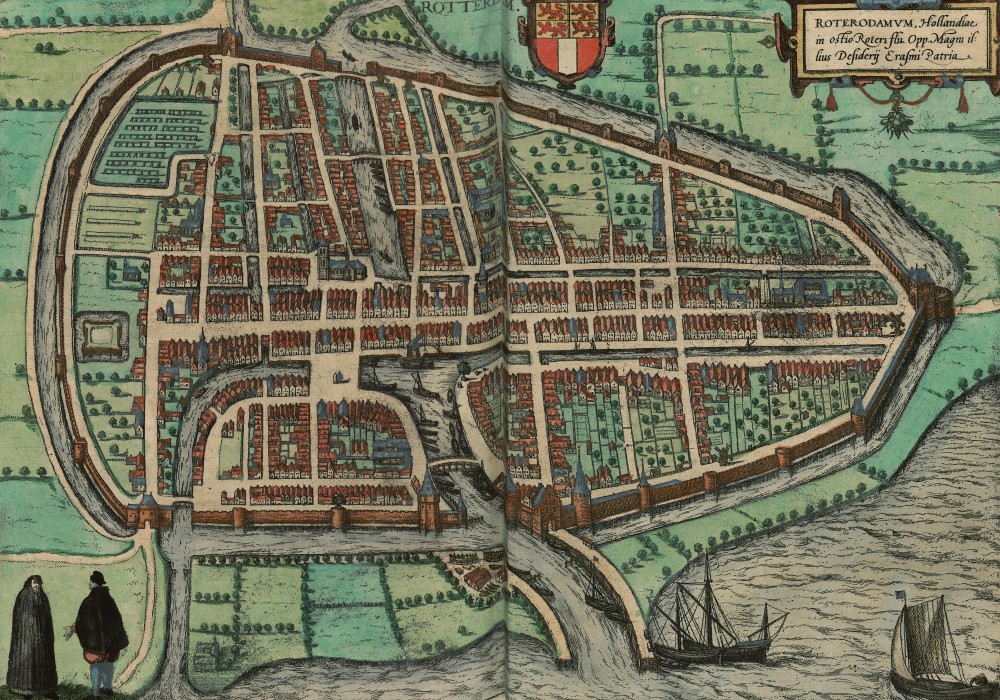

Rotterdam, 1588

The bird’s-eye view of Rotterdam shows a fortified city with walls and a moat. The moat is filled with water from a river (Nieuwe Maas). Rotterdam appears quite large, with wide, open areas within its walls that haven’t yet been built on. Both images portray the city as a trading port.

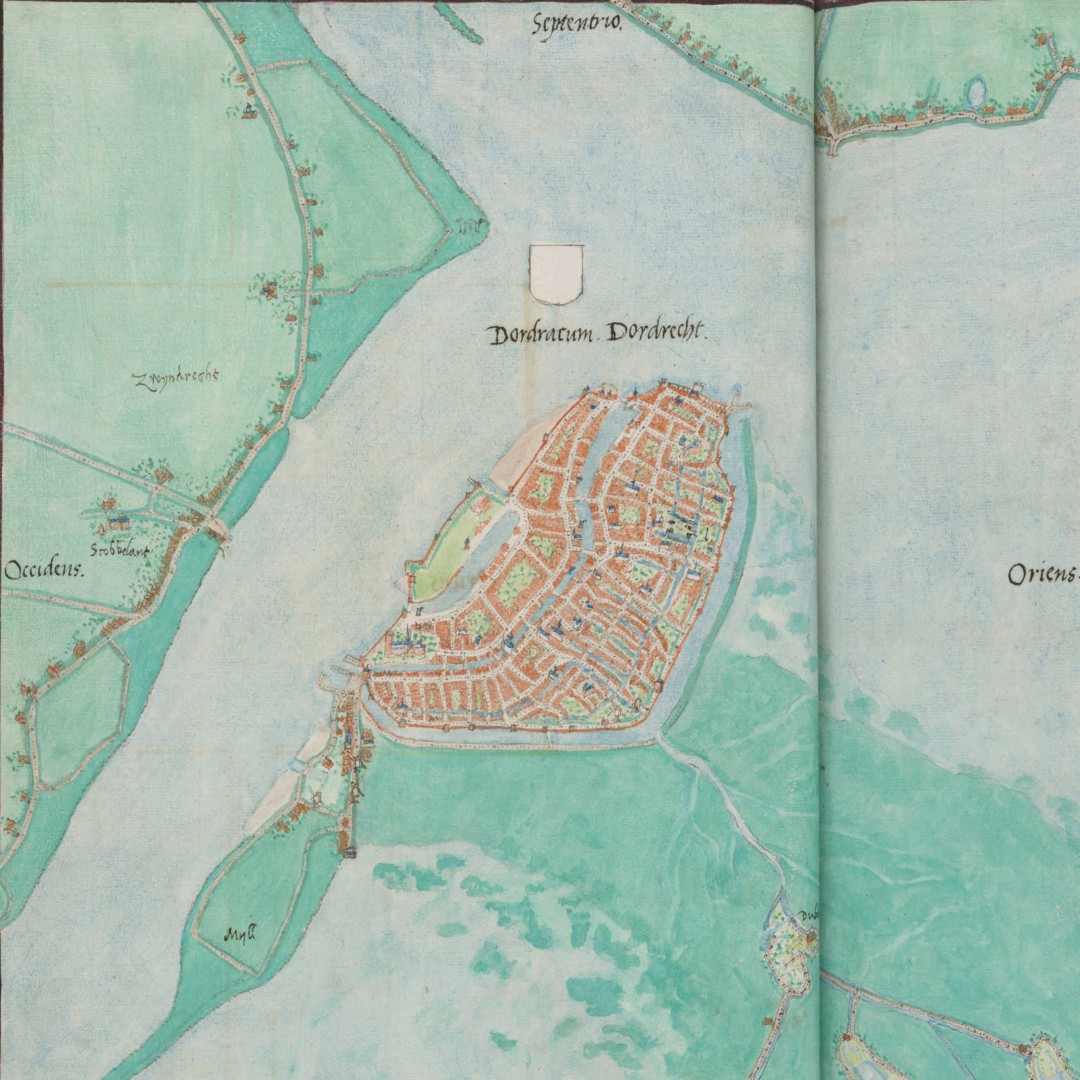

The Meuse delta with Rotterdam on the left and Dordrecht at the top of the map.

In Rotterdam, Kiechel and the two merchants hired a boat to travel to Dordrecht. A woman and two girls also accompanied them. At first, the wind was gentle but grew stronger once they moved some distance from the port. The boat began to lean to one side, sitting deeper in the water, and everyone on board got wet.

One of the naval charts from the “Spieghel der zeevaerdt” depicts the Rhine-Meuse-Scheldt delta and its numerous islands. The chart is oriented towards the southeast, with Rotterdam on its left side. Dordrecht appears in the upper left corner of the map on an island surrounded by the tidal wetlands of the Biesbosch. The boat Kiechel used would have sailed along the Nieuwe Maas and then into the Noord River towards Dordrecht.

Dordrecht

In the evening, the boat and its passengers arrived in Dordrecht. Kiechel describes the city as large and uninviting, with dark streets. He notes: Dordrecht is on an island, surrounded by water. If someone is to be executed, they must be brought across the water because the site of execution is on the other side. If someone goes for a walk and reaches a gate, they must turn back since it is impossible to proceed further due to the water.

Dordrecht from the North

The traveller also mentions that fish are cheap, especially salmon, which is caught there. Dordrecht is the last city in the province of Holland and lies five miles from Delft.

Dordrecht, 1575

The views of Dordrecht in the “Civitates” support Kiechel’s description. The first view shows the city in profile, situated on an island in the river Merwede and enclosed by a wall. In the lower-left corner of this view, a legend identifies nineteen buildings by name, including three inns.

The second depiction of Dordrecht provides a bird’s-eye view. Like the profile view, the city appears as an island. Various ships on the river indicate commercial activity. In the upper right corner of the map, the tidal wetlands of the Biesbosch are visible. A broad canal runs through the city, and large open spaces can still be seen within Dordrecht’s walls. These spaces seem to be gardens and orchards.

Dordrecht, 1581

Dordrecht was not always an island. In 1421, a storm in the North Sea caused a breach in the dykes, resulting in large areas of Zeeland and southern Holland being submerged in what became known as the St. Elizabeth’s Flood. The disaster significantly reshaped the Rhine-Meuse delta. The land south of Dordrecht was inundated and transformed into tidal wetlands. While some of this area has been reclaimed over time, the Biesbosch is now a Dutch national park.

An exceptionally lifelike view of Dordrecht was made by the Flemish artist Anton van den Wijngaerde (1525-1571) in 1545. He presents the city in profile view, with some of its surrounding landscape visible. Van den Wijngaerde worked in the service of King Philip II of Spain and produced panoramic views of various European cities. Although most of these cities were in Spain, van den Wijngaerde also drew remarkable views of Dutch cities and an impressive panorama of London. His work was based on observations made from different viewpoints and preliminary sketches. The results of his careful observations were always very lifelike, as he often included scenes of local life.

The final image of the city I wish to highlight is a remarkable map by the Dutch artist and cartographer Jacob van Deventer. The map is divided into two sections: one showing the city from a high vantage point, highlighting much of the surrounding countryside and emphasising the island-like character of Dordrecht. The other section is focusing on the city itself, displaying the layout of its streets and canals.

Illustrations & References

All images are in order of appearance with links to sources on external websites:

- Hogenberg, Frans, Moord op Willem van Oranje, 1584, c. 1591; Rijksmuseum Amsterdam.

- van Goyen, Jan, Oostpoort in Delft, 1606 – 1656; Rijksmuseum Amsterdam.

- Delft, in: Braun, Georg, Hogenberg, Frans, Civitates Orbis Terrarum (3), Cologne 1593, fol. 29v; Heidelberg University.

- Vermeer, Johannes, View of Houses in Delft, Known as ‘The Little Street’, 1658; Rijksmuseum Amsterdam.

- Key, Adriaen Thomasz., Portrait of William I, Prince of Orange, c. 1579; Rijksmuseum Amsterdam.

- Hogenberg, Frans, Moord op Willem van Oranje, 1584, c. 1591; Rijksmuseum Amsterdam.

- Hogenberg, Frans, Executie van Bathasar Gerards, 1584, Rijksmuseum Amsterdam.

- Rotterdam, in: Braun, Georg, Hogenberg, Frans, Civitates Orbis Terrarum (3), Cologne 1593, fol. 31v; Heidelberg University.

- Rotterdam, in: Braun, Georg, Hogenberg, Frans, Civitates Orbis Terrarum (4), Cologne 1594, fol. 13v; Heidelberg University.

- Waghenaer, Lucas Jansz., Teerste [-tweede] deel vande Spieghel der zeevaerdt, Leiden 1585, fol. 3v; Utrecht University Repository.

- van Goyen, Jan, View of Dordrecht from the North, 1650; National Gallery of Art, Washington D. C.

- Dordrecht, in: Braun, Georg, Hogenberg, Frans, Civitates Orbis Terrarum (2), Cologne 1575, fol. 24v; Heidelberg University.

- Dordrecht, in: Braun, Georg, Hogenberg, Frans, Civitates Orbis Terrarum (3), Cologne 1593, fol. 28v; Heidelberg University.

- Deventer, Jacob van, Planos de ciudades de los Países Bajos. Parte III [Manuscrito], 1545, p. 16); Biblioteca Nacional de España.

- Die Reisen des Samuel Kiechel aus drei Handschriften, K. D. Haszler (ed.), Stuttgart 1866, p. 17; Bayerische Staatsbibliothek. ↩︎