“We spent only half an hour in Dokkum because a boat was about to leave for Leeuwarden. On the boat were twenty-five passengers, which travelled along a narrow river less than fifteen steps wide.“1

From Dokkum to Harlingen

25 July – 26 July 1585

Samuel Kiechel had entered the Dutch Republic after a brief voyage by ship. He had not planned to visit Dokkum and other towns in West Frisia, but adverse wind conditions at sea had made returning to land more practical. Now, he was travelling westward towards Harlingen, where perhaps a ship might depart for Amsterdam.

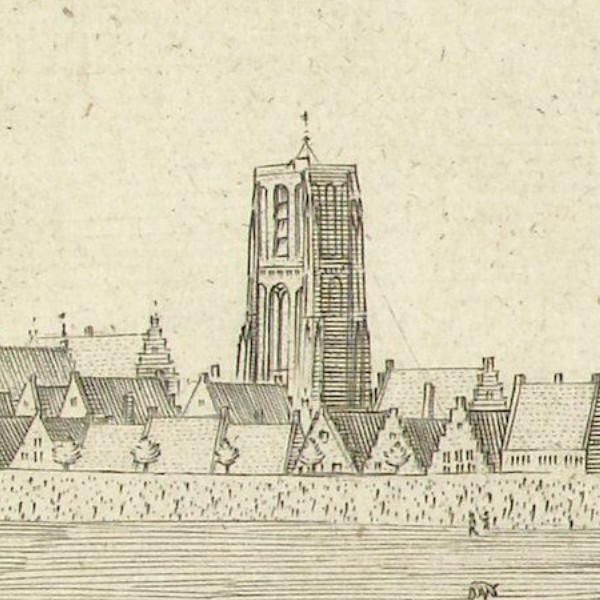

Dokkum

After disembarking, Samuel Kiechel and his two Dutch companions walked from the coast to Dokkum. Today, Dokkum is landlocked, but in the sixteenth century, it still had access to the sea through an inlet from the Lauwerszee, then known as the Dokkummer Diep. However, due to the construction of locks and the gradual build-up of silt in the inlet, Dokkum eventually lost its connection to the North Sea.

Kiechel and his companions did not stay in the town. Shortly after arriving, they found a boat bound for Leeuwarden. The boat already carried twenty-five passengers and travelled along the narrow Dokkumer Ee.

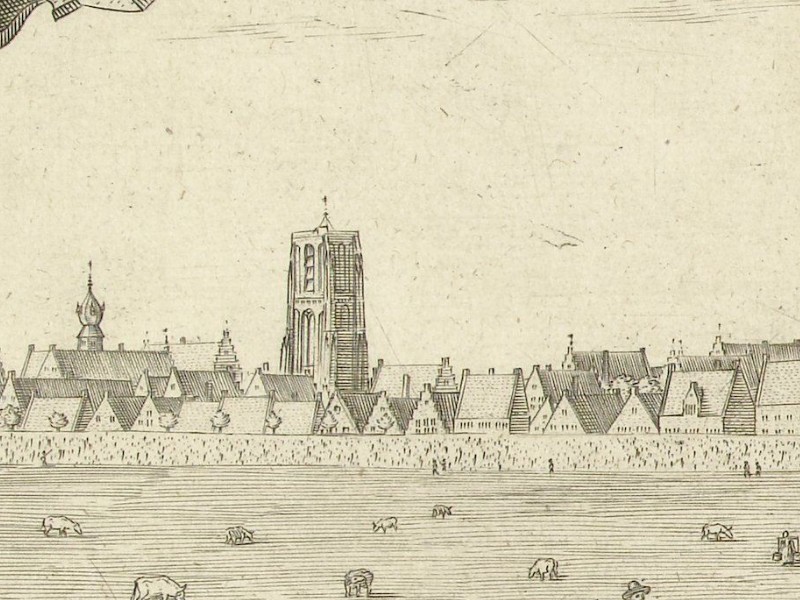

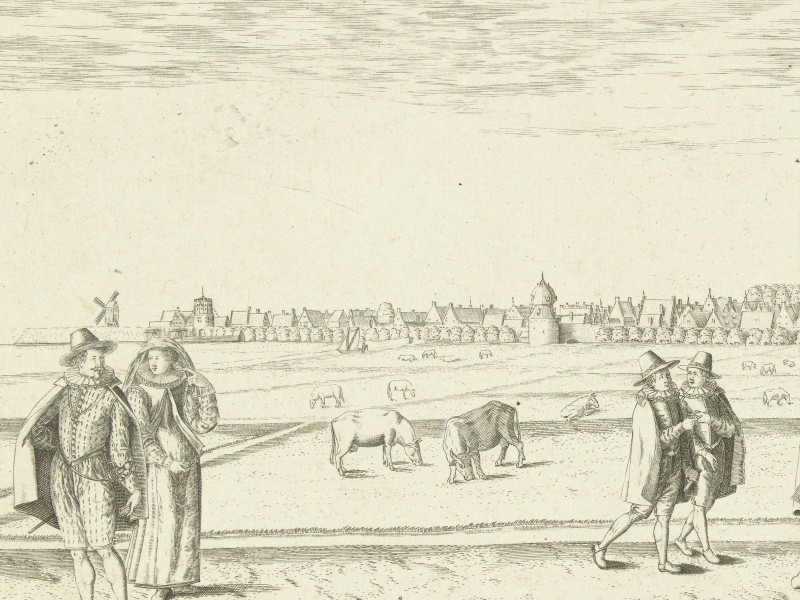

View of Dokkum, 1588

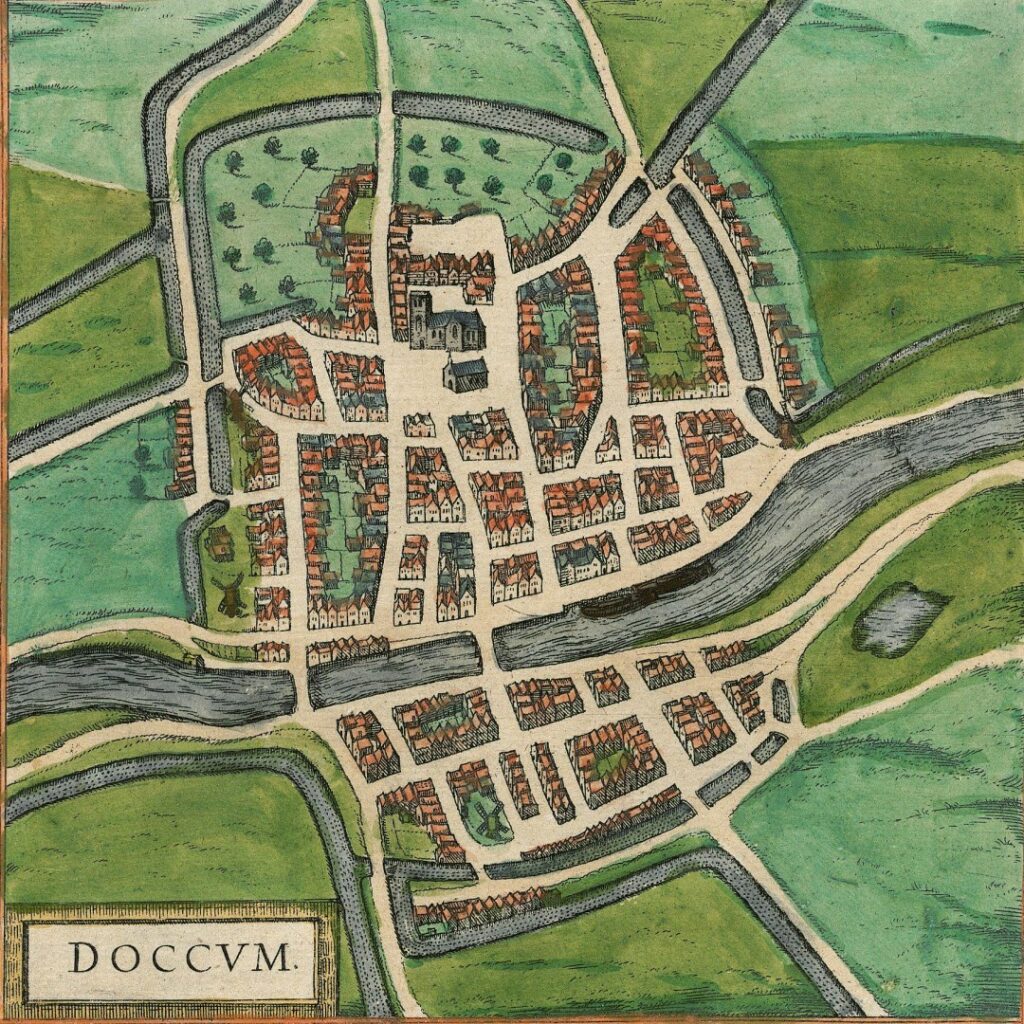

A bird’s-eye view in volume four of the “Civitates Orbis Terrarum” depicts Dokkum as a small, unfortified town surrounded by fields, with a river or canal running through it. Aside from the town’s name, the view offers no further details.

This fourth volume of the “Civitates” was first published in 1588, but the depiction of Dokkum was based on an earlier map created by Jacob van Deventer. Van Deventer (1500-1575) was a Dutch mathematician, surveyor, and cartographer. King Philip II of Spain commissioned him in 1559 to produce maps of all the major towns and cities in the Spanish Netherlands. His maps were notable for their time, resembling modern city plans with top-down views. Unlike other city depictions from that era, van Deventer’s maps did not focus on picturesque aspects. Instead of illustrating the many houses and structures typical of early modern cities, he concentrated on the layout, featuring detailed grids of streets, walls, gates, and churches, as well as the surrounding landscape beyond the city walls. The digital collection of the Biblioteca Nacional de España holds two volumes of his sketch maps, including the one of Dokkum.

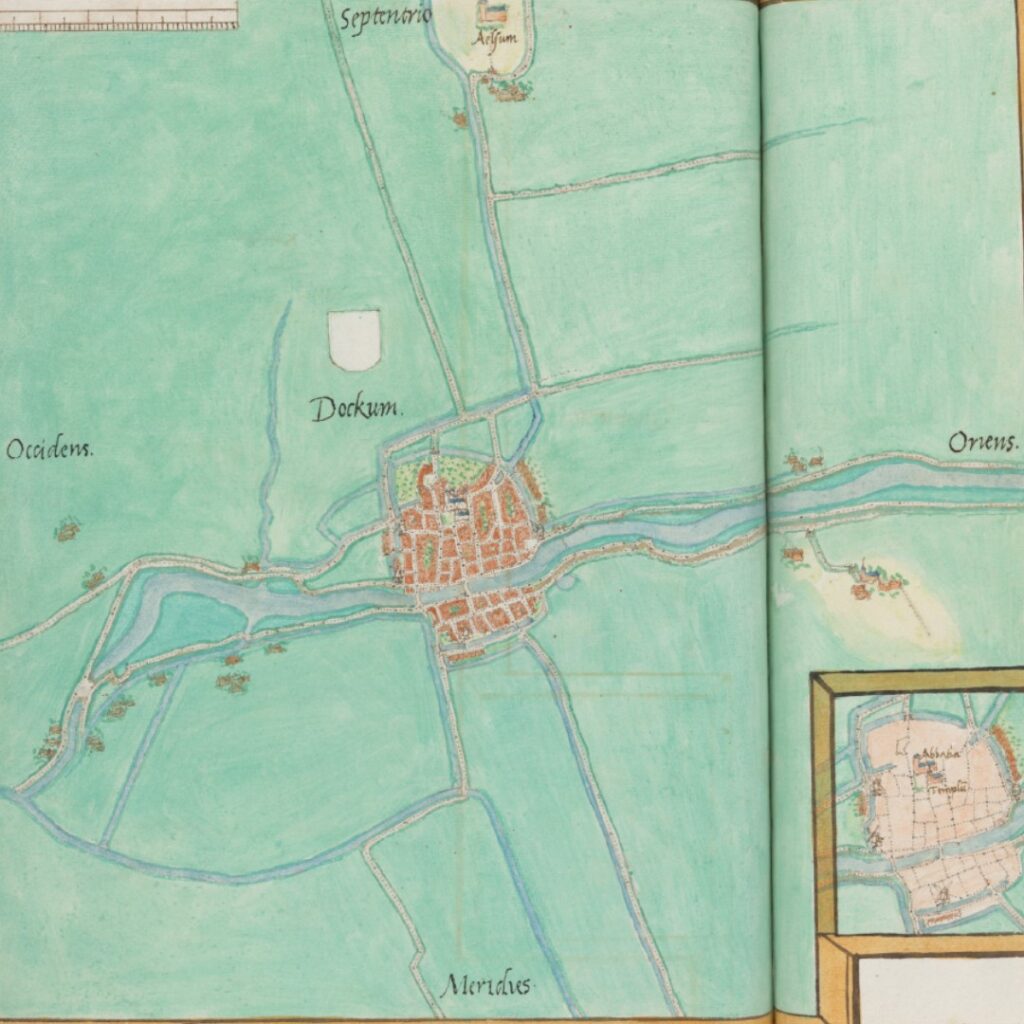

Jacob van Deventer’s map of Dokkum

Jacob van Deventer created his maps between 1559 and his death in 1575. The view of Dokkum was produced during this period. In the Eighty Years’ War, Dokkum was occupied by Spanish troops from 1572 to 1579. It later joined the Union of Utrecht, and as a defensive measure, city walls were built in 1581-82. By the time of Kiechel’s visit, Dokkum had changed from what was depicted on the map.

In van Deventer’s sketch map, the countryside around Dokkum is devoid of trees. A few roads extend from the city, and a river flows through Dokkum, connecting it to the Dokkummer Diep and the sea to the north-east. To the west, the river — more likely a canal — leads to Leeuwarden, along which Kiechel’s boat must have travelled. Several farmsteads and villages are visible along the water.

Leeuwarden

Samuel Kiechel’s journey to Leeuwarden was brief, as the distance was only twenty kilometres. Upon arrival, he and his companions were prevented from entering the city because the citizens were mustered and the gates were locked. Kiechel describes Leeuwarden as small but well-fortified. Since they could not gain entry, the three men joined other travellers and hired a boat to take them to Franeker along the same canal they had arrived on.

Mustering the citizenry was common in early modern Europe during times of war. The ability to defend themselves without relying on a local lord for security was a sign of a city’s autonomy. In case of an attack, the responsibility for protecting their homes fell to the citizens. All able men were expected to arm and equip themselves and be prepared to defend their walls. This was especially relevant in the Dutch provinces, which were embroiled in a war with Spain (the Eighty Years’ War), emphasising the urgency for town and city leaders to regularly rally their citizens for defence.

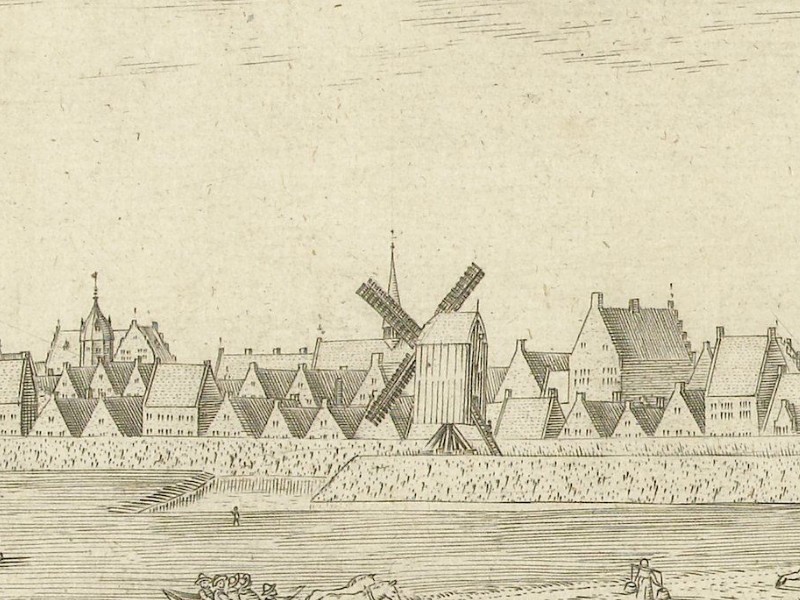

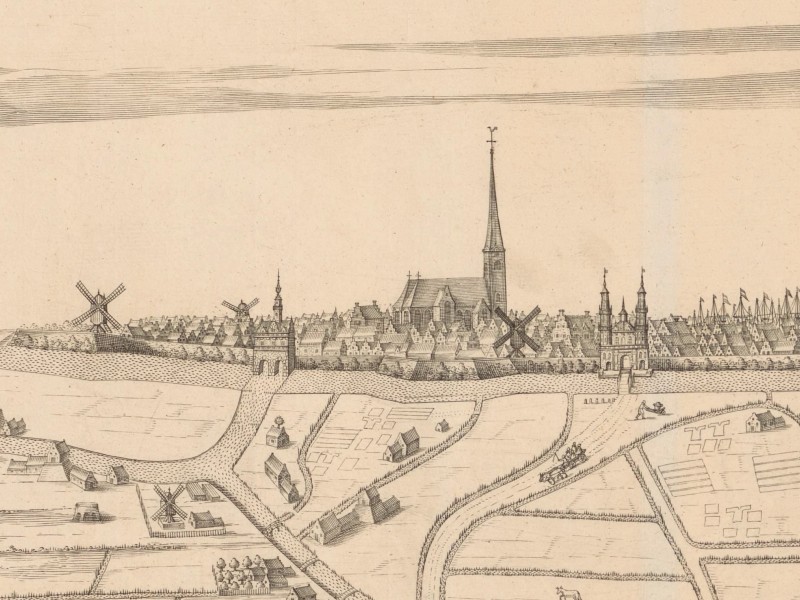

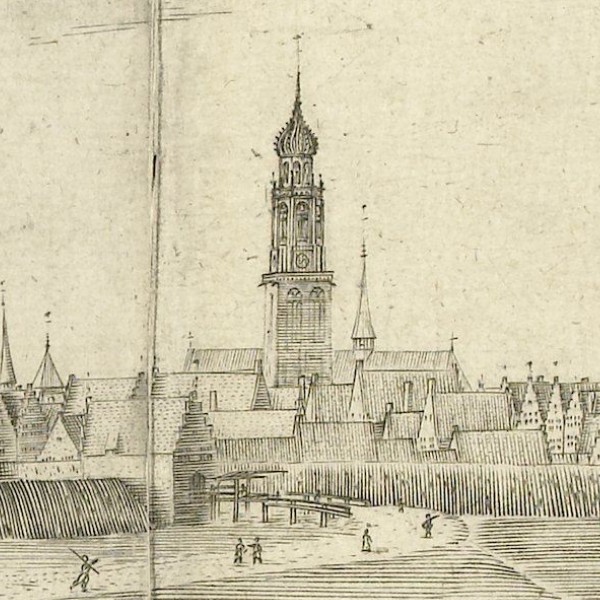

View of Leeuwarden, 1602

The Dutch mapmaker and engraver Pieter Bast created a profile and a bird’s-eye view of Leeuwarden, depicting the city from the south. The profile view shows Leeuwarden within its surrounding landscape, seen from a road leading into the city. Travellers on foot, horseback, and in carts are depicted arriving and departing. Fields and meadows surround the town.

Leeuwarden is depicted as a large and populous city with many sizeable houses behind its walls. Two prominent towers dominate the skyline. The square tower on the left is the Oldehove. Originally built as a church tower, construction was halted because it began to tilt. Although the church was demolished in the 1590s, the Oldehove remains and is open to visitors today. The second tower, situated in the centre of Leeuwarden, is the Sint Jacobstoren. After the Oldehove’s construction was abandoned, the citizens continued to demand a tall tower.

The Oldehove in Leeuwarden

Towers served both practical and symbolic purposes. Guards atop a tower acted as lookouts for approaching armies and identified dangers within the city, such as fires, before they spread out of control. Additionally, a tall tower symbolised the prosperity and wealth of a city. Many city views in the “Civitates Orbis Terrarum” show that tall towers, large churches, and imposing fortifications were essential features in most cities. It was not unusual for cities in a region to compete over who had the tallest tower. In Leeuwarden’s case, the Oldehove was built because the citizens wanted a taller tower than neighbouring Groningen. Due to its incomplete status, construction on the Sint Jacobstoren began in 1540 to satisfy the residents’ desire for a tall church tower. Ultimately, the Sint Jacobstoren also began to tilt and was demolished in 1884.

Sint Jacobstoren in Leeuwarden

Pieter Bast’s panorama of Leeuwarden also shows various smaller towers, municipal buildings, and windmills throughout the city. The prominent structure behind the walls on the right side of the view is the Blokhuis, which served as Leeuwarden’s former fortress. Construction started around 1500, with improvements to the fortifications made in the 1550s. After the cities of West Frisia joined the Union of Utrecht in 1579, the Blokhuis was converted into a prison.

Although Samuel Kiechel did not approach the city from the south, his general impression of Leeuwarden likely would have been similar to that of Pieter Bast’s profile view. Kiechel saw the Oldehove and Sint Jacobstoren rising above the cityscape. From his perspective, the Blokhuis would have been located on the left side of Leeuwarden.

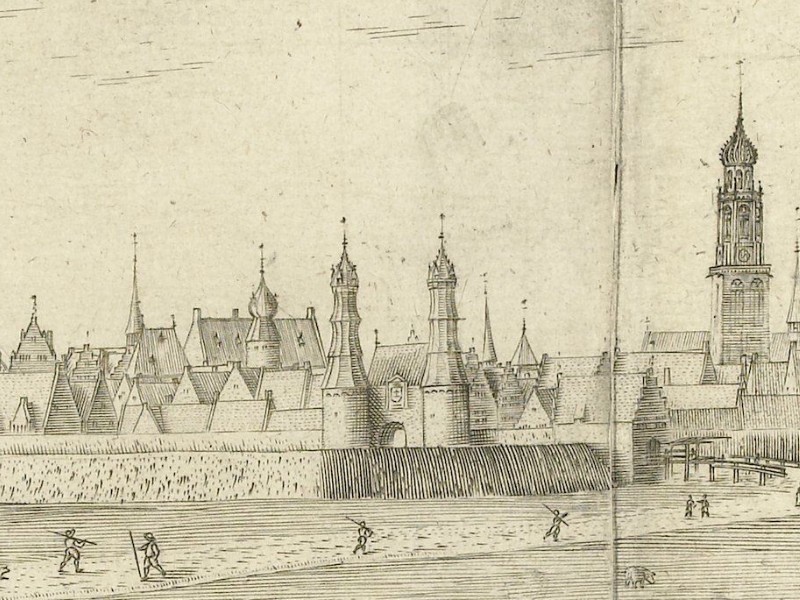

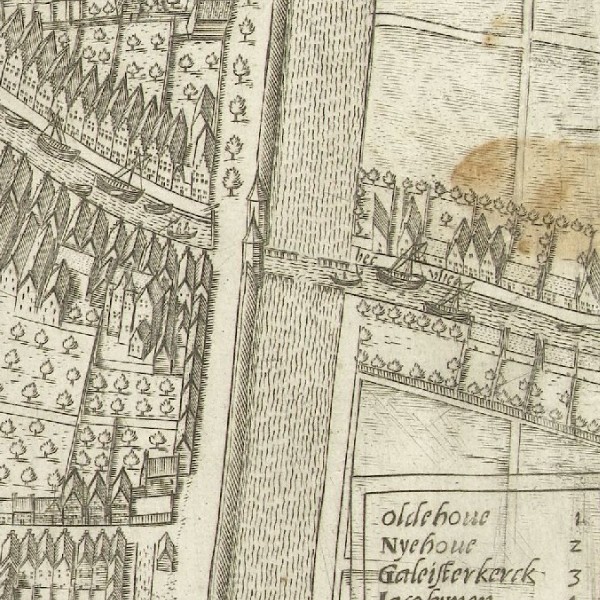

Bird’s-eye view of Leeuwarden, 1603

While Kiechel was not permitted to enter the city, Pieter Bast’s bird’s-eye view provides a glimpse behind the walls, as does Jacob van Deventer’s map. Bast depicts Leeuwarden as a densely populated place with rows of houses stretching everywhere. The Oldehove and Blokhuis are visible, though the surrounding houses somewhat obscure Sint Jacobstoren. Several broad canals run through the city.

The canal from Dokkum and a gate of Leeuwarden

On the right side of the image is the canal leading to Dokkum, where our traveller arrived from. Kiechel’s boat might have passed through the gate if the city had not been under lockdown. He likely had to disembark, or the boat might have turned into the canal surrounding Leeuwarden to bypass the town. In the lower-left corner is the canal that Kiechel’s boat entered to travel from Leeuwarden to Franeker.

Jacob van Deventer’s map of Leeuwarden illustrates the city set within a landscape of fields and meadows. Roads stretch out in all directions, and many farmsteads and villages are visible nearby, alongside the canals along which Kiechel arrived and departed. Inside Leeuwarden, van Deventer’s map shows the streets and canals crisscrossing the city. Though not as detailed as Bast’s two images, this map still conveys the impression of a large, wealthy and prosperous city.

Jacob van Deventer’s map of Leeuwarden

The Dutch Canal System

As the gates of Leeuwarden were closed, Samuel Kiechel did not stop but continued his voyage by boat to Franeker. Kiechel notes that the streams and rivers in the Dutch provinces often lack a current. With a favourable wind, boats sail along these waterways; in rougher weather, two or three men would walk along a path on the banks and tow the boat with long ropes. More men were needed to pull larger vessels.

The waterways Kiechel referred to as rivers were often canals. Our traveller hailed from a town in south-western Germany and presumably had little familiarity with the extensive network of canals in the Netherlands. The waterway between Dokkum and Leeuwarden was, in fact, a canal (Dokkumer Ee).

Towing boats and barges along the Dutch canals was a common practice. With its long history of reclaiming land from the sea and protecting it against floods, tides and storms, the Dutch landscape was dotted with dykes, polders and canals. The canals, built for drainage, served as the equivalent of roads for cargo and passenger transport. Similar to river travel in other countries, it was easier and more comfortable to travel by boat than by cart or on foot.

Regular tow routes were established in the second half of the sixteenth century, and towpaths were constructed. Samuel Kiechel noted that two or three men would pull a boat, but reliance on human muscle fell out of fashion at the time, leading to an increased use of horses. While Kiechel travelled along the old canals that had been deepened and widened for barges and boats, new canals were excavated specifically for this purpose in the seventeenth century. The ‘trekvaarten’ were purpose-built canals that connected centres of population, often in a straight line. The first such canal was the Haarlemmertrekvaart, which linked Amsterdam and Haarlem. Construction began in 1631, and it opened a year later. In West Frisia, the Harlingertrekvaart from Harlingen, through Franeker to Leeuwarden, was established in 1646, and a towpath was built.

Franeker

Samuel Kiechel arrived in Franeker in the evening and spent the night there. Unfortunately, he did not mention anything further about this place. However, both Pieter Bast and Jacob van Deventer created maps and views that give us an insight into what our traveller might have observed.

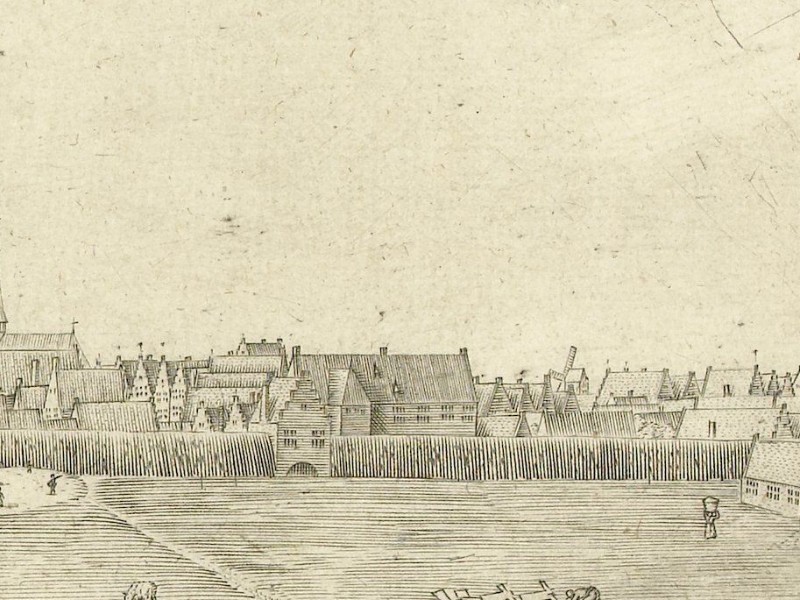

View of Franeker, 1598

Bast’s images of Franeker are from the north. The foreground of the profile view is filled with figures in contemporary clothing. These are decorative elements rather than scenes from daily life. Like Leeuwarden and Dokkum, the landscape around Franeker consists of fields and meadows. The town appears smaller than Leeuwarden, but its skyline is equally impressive. The Martini Church dominates Franeker’s silhouette, and we can see other large buildings, churches and towers.

On the left side of the profile view (east) is a canal with a boat approaching the town. This is the same canal from Leeuwarden that Kiechel arrived by. Aside from the figures in the foreground, Samuel Kiechel’s view of Franeker might not have differed significantly from Bast’s depiction.

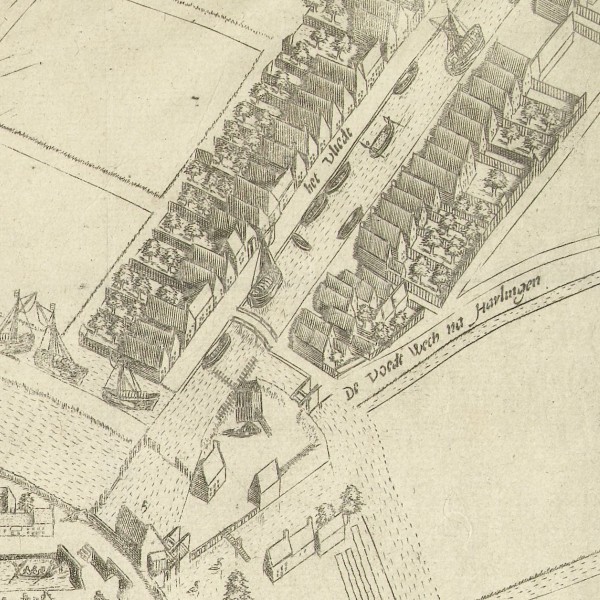

Bird’s-eye view of Franeker, 1598

The bird’s-eye view shows a sizeable, populated town. Multiple canals with boats crisscross the area. The Martini church dominates the centre, while the university is situated in the upper right corner of Franeker. The University of Franeker was the second-oldest Dutch university, opening on 29 July 1585, six days before Kiechel’s visit.2

Further to the right, at the edge of the bird’s-eye view, is a canal lined with numerous boats and a road. This road leads to Harlingen, and Kiechel would depart Franeker along this route the following morning.

The road from Franeker to Harlingen

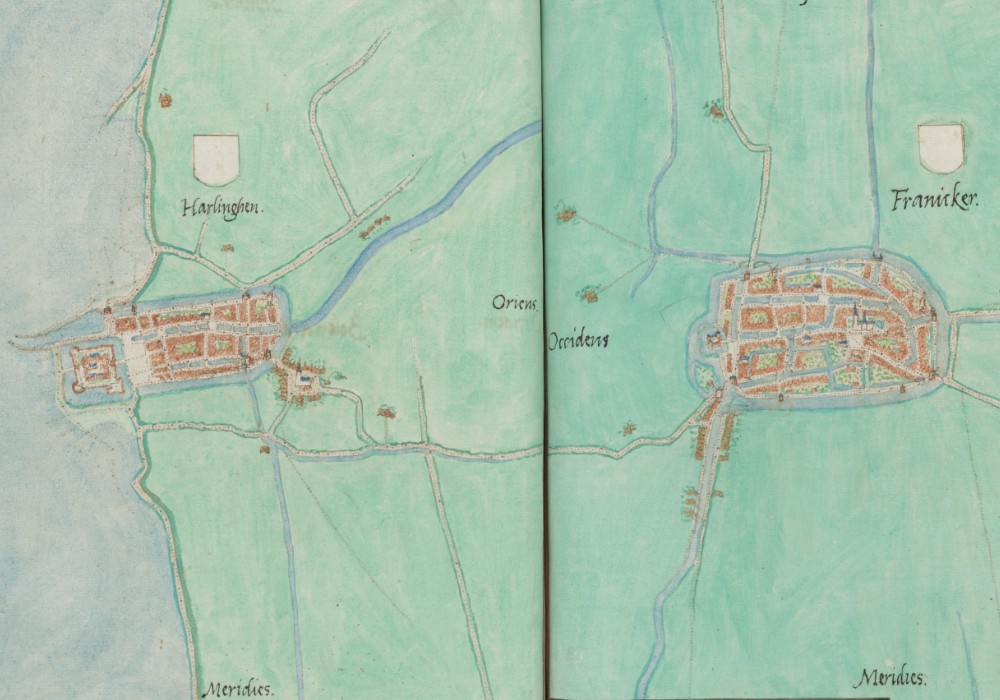

The maps of Franeker and Harlingen in Jacob van Deventer’s manuscript are placed side by side. Following the road from Franeker, the two images seem to connect, creating the illusion of a comprehensive view of the area through which Samuel Kiechel travelled. However, both locations are further apart, and a canal to the north of the road reveals that the connection is merely coincidental.

Jacob van Deventer’s maps of Franeker and Harlingen

Harlingen

Kiechel spent a night in Franeker and left for Harlingen on the morning of 26 July. According to our traveller, Harlingen was the largest Dutch city he had visited so far, situated on the North Sea coast. At the gate, Kiechel was required to state his name before being allowed entry. Once again, our traveller does not mention anything about the city, as he did not stay. Upon arrival, he learned that a ship was scheduled to leave for Amsterdam the same day. He chose to seize this opportunity and continue his journey.

Jacob van Deventer’s map of Harlingen

In contrast to Kiechel’s description, Harlingen appears relatively small on van Deventer’s map. However, as noted, the map was produced between 1559 and 1575. From 1579 onwards, Harlingen began to expand due to the influx of Protestant refugees fleeing religious persecution in the Spanish part of the Netherlands. On van Deventer’s map, there is a village and a large church to the southeast, outside Harlingen. The village, called Almenum, became part of Harlingen following the city’s first expansion in 1579-80. Its Grote Kerk still stands there today.

View of Harlingen, ca. 1614

A profile view from 1614 depicts Harlingen from the north. By then, it was a much larger city surrounded by fields, meadows, canals, farmsteads and villages. The Grote Kerk is prominent on the city’s left side (east). However, the silhouette is dominated by the numerous ships’ masts protruding above the rooftops. Harlingen served as an important commercial port at the entrance to the Zuiderzee. While the number of masts may have been exaggerated, similar to the representation of churches and towers in other views, their purpose was to highlight the prosperity and wealth of the city in this image.

Illustrations & References

All images are in order of appearance with links to sources on external websites:

- Anonymous, View of a River, c. 1635; Rijksmuseum Amsterdam.

- Dokkum, in: Braun/Hogenberg, Civitates Orbis Terrarum (4), Cologne 1594, fol. 18v; Heidelberg University.

- Dokkum, in: Deventer, Jacob van, Planos de ciudades de los Países Bajos. Parte III [Manuscrito], 1545, fol. 56; Biblioteca Digital Hispánica.

- Bast, Pieter, Gezicht op Leeuwarden vanuit het Zuiden, 1602; Rijksmuseum Amsterdam.

- Bast, Pieter, Plattegrond van Leeuwarden, 1603; Rijksmuseum Amsterdam.

- Leeuwarden, in: Deventer, Jacob van, Planos de ciudades de los Países Bajos. Parte III [Manuscrito], 1545, fol. 55; Biblioteca Digital Hispánica.

- van Goyen, Jan, Panoramic View of a River with Low-Lying Meadows, 1644; Rijksmuseum Amsterdam.

- Waterloo, Anthonie, Kerk aan het water, 1630 – 1663; Rijksmuseum Amsterdam.

- Bast, Pieter, Gezicht op Franeker, 1598; Rijksmuseum Amsterdam.

- Bast, Pieter, Plattegrond van Franeker, 1598; Rijksmuseum Amsterdam.

- Leeuwarden, in: Deventer, Jacob van, Planos de ciudades de los Países Bajos. Parte III [Manuscrito], 1545, fol. 53-54; Biblioteca Digital Hispánica.

- de Baudous, Robert, Stadsgezicht van Harlingen met lofdicht, c. 1614; Rijksmuseum Amsterdam.

- Die Reisen des Samuel Kiechel aus drei Handschriften, K. D. Haszler (ed.), Stuttgart 1866, pp. 14-15; Bayerische Staatsbibliothek. ↩︎

- Kiechel dated his arrival in Franeker on 25 July 1585. All dates in the journal follow the Julian Calendar. In the Gregorian Calendar, the date would be 4 August. ↩︎