“Walcheren is only twelve Dutch miles in circumference. In the summer, it is possible to ride around the island in one day. Four cities are on the island: Arnemuiden, Veere, Middelburg and Vlissingen. Fort Rammekens is also on the island.“1

From Dordrecht to Vlissingen

3 August – 5 September 1585

Samuel Kiechel had travelled by cart and boat through the provinces of the independent Dutch Republic. His destination was Vlissingen, the westernmost city of the republic, just across the water from Spanish-held Flanders. From Vlissingen, ships left for England. But Kiechel’s hope for quick progress was dashed by the weather and strong eastward winds.

Sailing Through Zeeland

Leaving Dordrecht

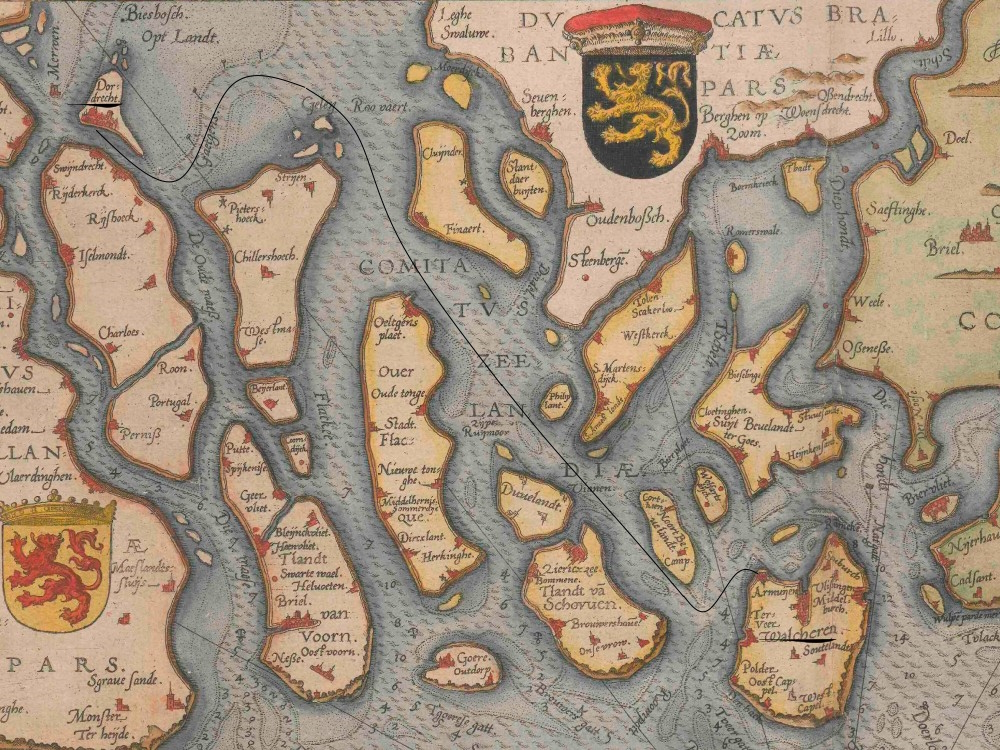

Samuel Kiechel departed Dordrecht by ship, heading for Walcheren, the westernmost of the Dutch islands near Flanders. The route to Walcheren took him through Zeeland, a Dutch province that includes the vast delta of the Scheldt, Meuse and Rhine Rivers. Islands, river arms and canals dominate the landscape of Zeeland.

Kiechel’s journey through Zeeland

Kiechel’s vessel probably sailed along Hollands Diep around the southern tip of the island of Hoeksche Waard. According to a nautical chart from that period, tidal wetlands surrounded the island. The ship then continued westward along the waterways that separate the mainland from Zeeland’s islands.

Our traveller noted that they passed flooded lands along the route and saw various buildings protruding above the water. The Rhine-Meuse-Scheldt delta has always been prone to flooding. The land surrounding the delta is low-lying, so heavy storms from the North Sea or damaged dykes could easily cause floods. As mentioned, Dordrecht became an island after a devastating flood in 1421.

Fifteen years before Samuel Kiechel’s visit, the All Saints’ Flood of 1570 struck Zeeland, causing widespread devastation. It was one of the worst natural disasters of its era, submerging large areas that would only be reclaimed centuries later. From the boat, Kiechel saw the remnants of towns and villages swallowed by water. It was not until the twentieth century, with the construction of the Delta Works, that a long-term effort to prevent such flooding was undertaken.

Travelling Around Walcheren Island

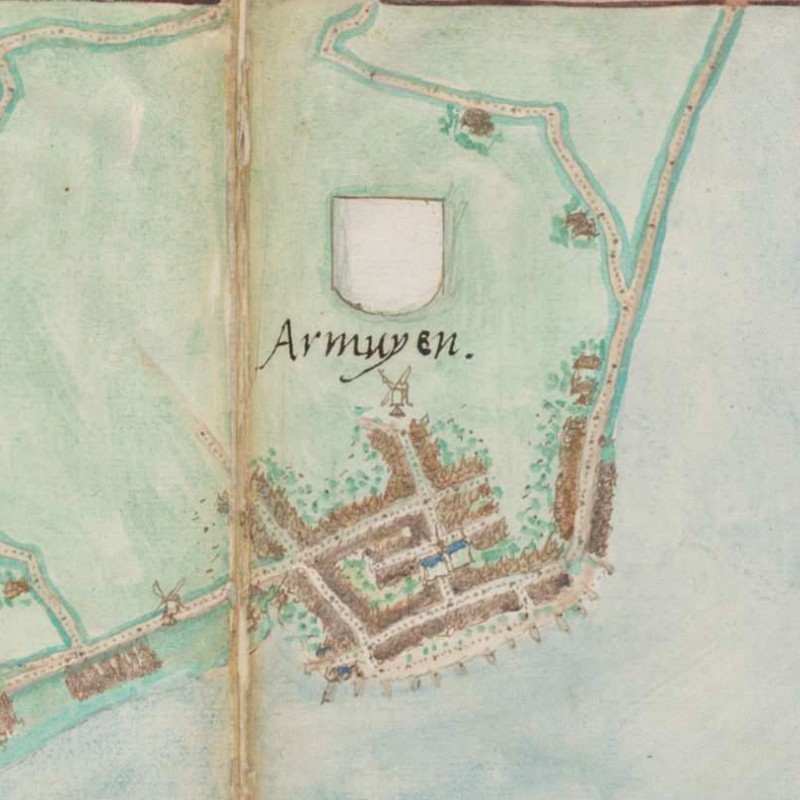

Kiechel’s ship sailed through the night and arrived in Arnemuiden the following morning. Our traveller noted that the town was in the province of Zeeland. It was small and fortified by poorly constructed walls.

In the sixteenth century, Arnemuiden was on the southern coast of Walcheren. Today, however, it is no longer connected to the sea. In 1871, the Sloedam was built to connect Walcheren to the mainland, and after World War II, the land around the dam was reclaimed and poldered. The island of Walcheren is now a peninsula.

Map of Arnemuiden

Jacob van Deventer mapped the towns and cities on Walcheren. The maps are drawn in plan view, showing the streets, canals and roads leading in and out of each place. As Walcheren was a small island, it is possible — considering the geographical location of each place relative to the others — to follow the roads Kiechel took around the island on van Deventer’s maps.

Our traveller did not stay in Arnemuiden but walked to Veere on the island’s eastern side, presumably along the coastal road. Veere, he writes, was small but well-fortified and mainly populated by fishermen.

Veere

Middelburg

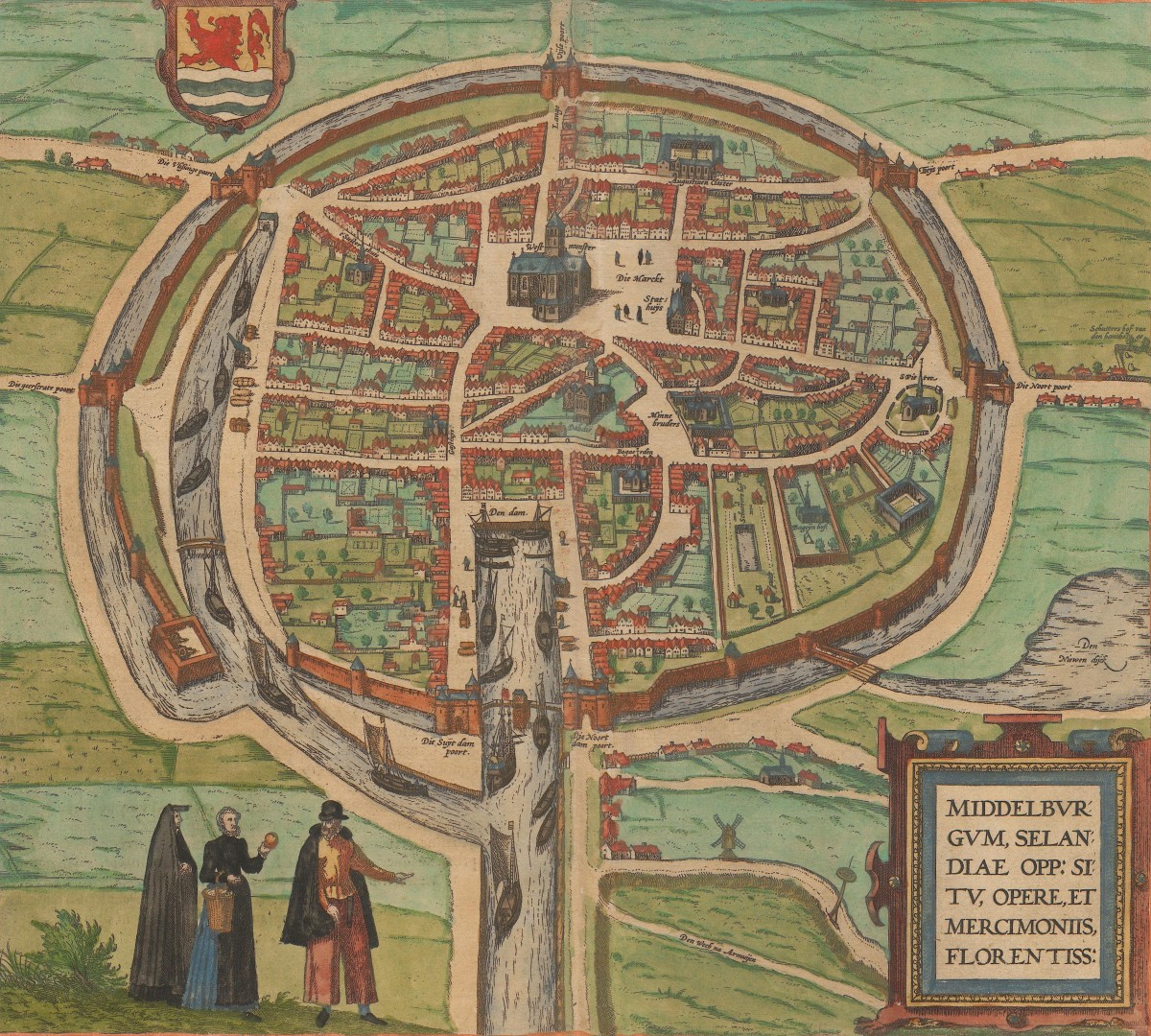

After a short break, Kiechel walked another mile to Middelburg, the capital of Zeeland, situated in the middle of the island. According to the traveller, Middelburg was a large and densely populated city. However, Kiechel saw many houses that had been destroyed and not rebuilt. The siege of 1572-1574 may have caused the damage. During the Eighty Years’ War, Middelburg was the last city held by the Spanish on Walcheren. Dutch rebels besieged it, and eventually, the city surrendered.

According to the journal, Middelburg was one mile from the sea, but ships could access it via a canal. Before the war, the city had been an important commercial centre, with its merchants regularly sailing to Spain. Now, the ships were at risk of being boarded and their cargo seized.

Middelburg, 1575

A bird’s-eye view in the second volume of the “Civitates Orbis Terrarum” shows Middelburg as a fortified city with large open spaces inside the walls. This volume of the “Civitates” was first published in 1575, and depending on when the print was made, it might depict the city after the siege. The open areas suggest this possibility. While small gardens were not uncommon in medieval and early modern cities, the norm was that construction space for houses was usually limited, especially in a busy trading port. At the bottom of the image are Middelburg’s harbour and the canal leading to the sea. Ships are moored on the canal and within the city, but they are of moderate size. Nevertheless, Middelburg recovered from the siege and went on to become one of the wealthiest and largest cities in the Dutch Republic during the seventeenth century.

After spending the night in Middelburg, Samuel Kiechel travelled by cart to Vlissingen (5 August) on the western coast of Walcheren. The road to Vlissingen is marked in the bird’s-eye view, located in the top left corner. However, the view is not oriented towards the north, so in van Deventer’s map, the road appears in the bottom left corner.

Vlissingen

Samuel Kiechel visited the towns of Walcheren in just over a day. Regarding the island’s size, he noted it had a circumference of twelve Dutch miles, and in summer, one could ride around it in a single day. The only larger settlements on Walcheren were Arnemuiden, Veere, Middelburg and Vlissingen, along with Fort Rammekens. The fortress was an hour from Vlissingen, and Kiechel visited it. He mentioned that one part of the fortress was built into the sea, while another part was on land and always garrisoned.

Waiting in Vlissingen

Kiechel’s impression of Vlissingen was of a small but heavily fortified place with an inlet from the sea leading into the town. The Prince of Orange, when he was still alive, had a residence in Vlissingen, and now, his widow still lived there.

Our traveller learned of a unique defensive measure of the townspeople against attacks. The citizens of Vlissingen could flood the surrounding countryside by opening the sluice gates of the inlet. This was a common tactic employed by the Dutch during their war against Spain. To halt the advancing Spanish armies, the Dutch would open the sluice gates and flood the surrounding polders to block or force back their enemies.

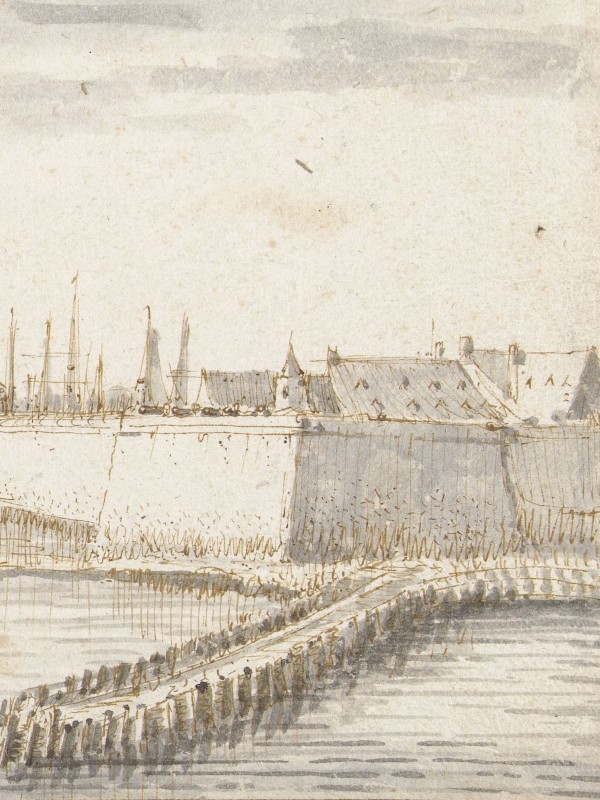

Vlissingen, 1598

A bird’s-eye view of Vlissingen from the southeast is in the fifth volume of the “Civitates Orbis Terrarum”. In the view, the town and particularly the harbour area are heavily fortified. The above-mentioned inlet from the sea runs through Vlissingen. None of the buildings in the image is identified by name. The city’s main church is illustrated on a larger scale than the surrounding buildings. Along the coastline on both sides of the town, we see the dykes that were constructed to protect the reclaimed land and prevent flooding.

Forced Stopover

Samuel Kiechel did not intend to stay in Vlissingen; he wanted to depart for England as soon as possible. However, because the wind constantly blew from the west, he had to wait in the town from 5 August to 6 September. Despite this hold-up, our traveller kept himself busy; he made two unsuccessful attempts to continue his voyage.

The first attempt was on 27 August when the wind finally shifted. Kiechel prepared to leave and went on board a ship. But then, the wind changed course again in the evening, forcing him to return to the town.

The second attempt to leave Vlissingen soon followed. Kiechel overheard that some Frenchmen had paid the captain of a privateer ship to take them to Calais in France. Bored with waiting in Vlissingen, he decided to join them on their voyage.

As a side note, Kiechel spoke French. Later in his journal, he mentions that he had spent a few months in Paris before his journey, using that time to learn the language.

Our traveller had learnt that he needed a passport from the mayor of Vlissingen if he wished to leave by ship. He went to the town hall but was told that the city council had instructed the mayor not to issue any more passports for journeys to France. However, it was still possible to obtain a passport to England. Despite the potential difficulties that could arise from having the wrong papers, Kiechel decided to get one.

Vlissingen town hall, 1612

Unlike modern passports, early modern equivalents were issued only for a specific destination. The document was essentially an official letter with the traveller’s name and sometimes physical features. Travellers like Samuel Kiechel often had to acquire new passports from local authorities, especially in regions affected by war or plague.

Samuel Kiechel took the passport for England as a precaution. He explains in his journal that privateers, when they stopped a ship at sea, would question the passengers about their destination. A traveller with a passport would be left in peace, but without it, he risked being robbed. Following Kiechel’s reasoning, it was essential to have a passport at sea. The destination for which the passport was issued was of lesser importance. Presumably, since sailing ships relied on the wind, there was always a chance of being blown off course — as Kiechel would later discover to his advantage.

With his passport to England in hand, our traveller boarded the French privateer bound for Calais. The ship’s captain informed Kiechel that he could not take passengers without the mayor’s permission (passport). Kiechel showed him his passport, and he was allowed on board. The captain either did not read it or did not care.

The ship set sail on the afternoon of 31 August despite strong winds and a rough sea. It sailed throughout the rest of the day and night but made little progress. The wind and heavy seas eventually forced the ship back to Vlissingen.

Upon returning to the port on 1 September, all passengers had to show their passports at the gate before being allowed into the city — a routine security check to ensure no one without the proper papers had been on the ship. It did not matter that the vessel had left Vlissingen the day prior.

Now, Samuel Kiechel was very worried. While he possessed a passport, it was not issued for a journey to France, and he had just disembarked from a French ship heading for Calais. Our traveller noted that if he was caught, he would not have been permitted to enter Vlissingen again. Given that the Dutch were at war with Spain, there might have been harsher consequences. However, not being allowed into Vlissingen meant Kiechel would need to find another port to continue his journey to England.

Fortunately for him, the poor weather worked in his favour. The guard at the gate, unwilling to spend too much time in the rain, merely glanced at his document and waved him through.

Smugglers

The heightened security measures in Vlissingen were not solely a result of the Dutch war against Spain in general. The island of Walcheren was positioned in a strategically vital location at the mouth of the Scheldt River. Further along the Scheldt was Antwerp, the most important trading hub of the period, which was under Spanish siege. Vlissingen served as the key port on the island, and its ships could target or at least harass all Spanish maritime traffic entering or leaving the Scheldt. Ships from Walcheren would play a vital role three years later when the Spanish Armada was defeated off the coast of Flanders (1588).

The proximity of Flanders not only meant a constant threat of Spanish attacks, but also collaboration and treachery. On the day Kiechel returned to Vlissingen, a boat loaded with cheese, butter, and herring arrived along with five prisoners. The prisoners were smugglers who had supplied the Spanish with provisions. They had been caught sailing up the Scheldt to Antwerp. Kiechel reports that three of the prisoners were flogged, and their two leaders were sentenced to hang. The two convicts were taken across the estuary of the Scheldt to Flanders and executed in view of the Spanish army.

England and the Dutch Revolt

During Samuel Kiechel’s time in Vlissingen, the Dutch Republic and England signed the Treaty of Nonsuch (10 August 1585). Queen Elizabeth I agreed to provide troops to lift the siege of Antwerp and to pay a yearly subsidy to support the Dutch rebellion. In return, English garrisons were stationed in the towns of Brill and Vlissingen, as well as at Fort Rammekens, until the Dutch repaid the loan. They achieved this in 1616. Robert Dudley, 1st Earl of Leicester, was sent to command the English forces.

While Kiechel waited in Vlissingen, he observed ships from England arriving daily, bringing soldiers to lift the siege of Antwerp. On 29 August, the commander of the English army arrived. According to our traveller, he was called “Mylord Oxford” and was received in the city with great fanfare. It appears that the news of Antwerp’s surrender to the Spanish on 17 August 1585 had not yet reached Vlissingen.

After waiting a month in Vlissingen, the wind finally shifted. On 6 September, Samuel Kiechel boarded a French privateer in his third and final attempt to leave the city.

Illustrations & References

All images are in order of appearance with links to sources on external websites:

- Ortelius, Abraham, Theater of the World, Antwerp 1587, fol. 39v; Library of Congress.

- Cuyp, Aelbert, Gezicht op Dordrecht, 1630 – 1691; Rijksmuseum Amsterdam.

- Waghenaer, Lucas Jansz., Teerste [-tweede] deel vande Spieghel der zeevaerdt, vande navigatie der Westersche Zee, innehoudende alle de custen van Vranckrijck, Spaignen ende ‘t principaelste deel van Engelandt, in diversche zee caerten begrepen, Leiden 1585, fol. 3v; Utrecht University Repository.

- van Goyen, Jan, Ruïne van het Huis te Merwede, 1638; Rijksmuseum Amsterdam.

- Arnemuiden, in: Deventer, Jacob van, Planos de ciudades de los Países Bajos. Parte III [Manuscrito], 1545, p. 4; Biblioteca Nacional de España.

- Veere, in: Deventer, Jacob van, Planos de ciudades de los Países Bajos. Parte III [Manuscrito], 1545, p. 2; Biblioteca Nacional de España.

- Middelburg, in: Deventer, Jacob van, Planos de ciudades de los Países Bajos. Parte III [Manuscrito], 1545, p. 3; Biblioteca Nacional de España.

- Middelburg, in: Braun, Georg/Hogenberg, Frans, Civitates Orbis Terrarum (2), Cologne 1575, fol. 28v; Heidelberg University.

- Vlissingen, in: Deventer, Jacob van, Planos de ciudades de los Países Bajos. Parte III [Manuscrito], 1545, p. 1; Biblioteca Nacional de España.

- de Verwer, Abraham, Gezicht op Vlissingen, 1600 – 1650; Rijksmuseum Amsterdam.

- Vlissingen, in: Braun, Georg, Hogenberg, Frans, Civitates Orbis Terrarum (5), Cologne 1599, fol. 28v; Heidelberg University.

- Nooms, Reinier, Large Sailing Vessel and Rowing Boat, 17th century; Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York.

- de Verwer, Abraham, Gezicht op Vlissingen, vanaf de Schelde gezien, 1600-1650; Rijksmuseum Amsterdam.

- van Borssom, Anthonie, Galgenveld aan de rand van de Volewijk, 1664 – 1665; Rijksmuseum Amsterdam.

- Die Reisen des Samuel Kiechel aus drei Handschriften, K. D. Haszler (ed.), Stuttgart 1866, pp. 18-19; Bayerische Staatsbibliothek. ↩︎